The past 15 years have seen an exciting run of creative scientific advances in fabricating three-dimensional (3-D) structures by self-folding of 2-D sheets, but the complexity of structures achieved to date falls far short of what can easily be folded by hand using paper - yes, origami still beats your 3-D printer.

The Japanese art of origami has been a source of inspiration for scientists working to construct such 3D forms and the limitation has been beneficial up to now but simple shapes in 2015 will hold up development of new applications in areas such as biomimetic systems, soft robotics and mechanical meta-materials, especially for structures on small length scales where traditional manufacturing processes fail. A team has developed an approach that could open the door to a new wave of discoveries.

Polymer scientists Ryan Hayward, Junhee Na, Arthur Evans and Christian Santangelo from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and collaborators have found a way to make reversibly self-folding origami structures on small length scales using ultraviolet photolithographic patterning of photo-crosslinkable polymers.

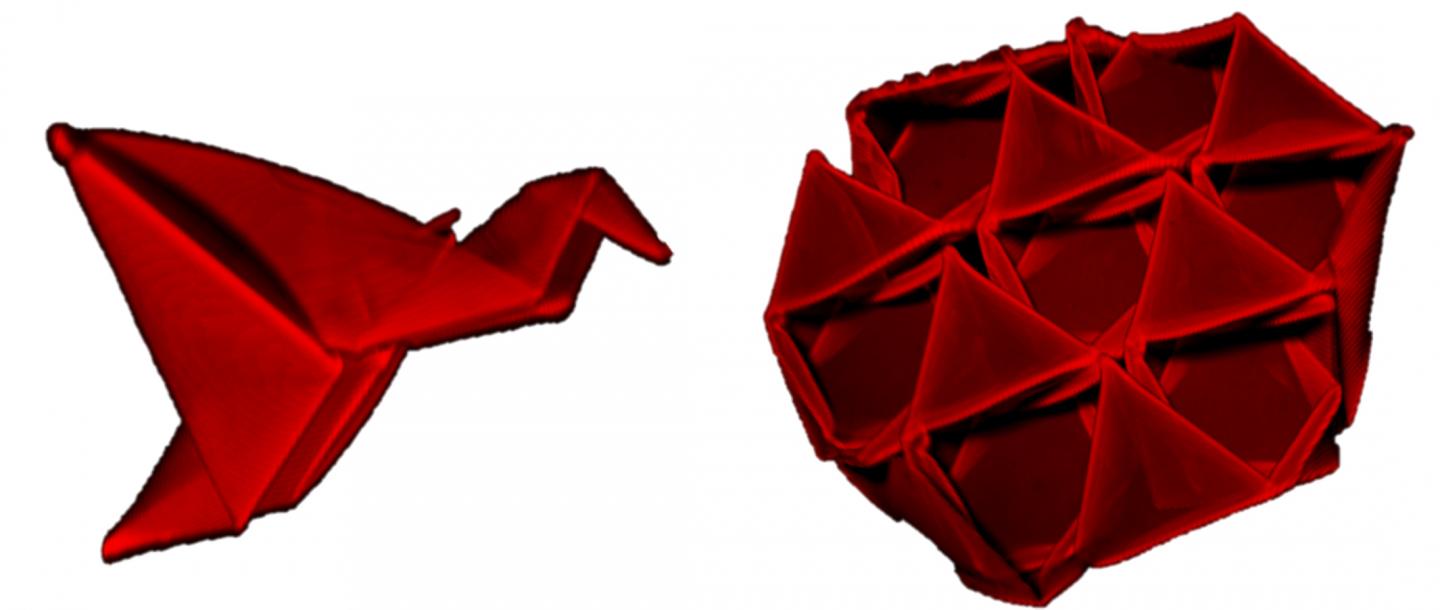

Three-dimensional reconstructions (from confocal fluorescence microscopy) of self-folded origami structures with overall dimensions slightly below 1 mm. Credit: UMass Amherst

Hayward says, "We have designed and implemented a simple approach that consists of sandwiching a thin layer of a temperature-responsive hydrogel with two patterned films of a rigid plastic. The presence of gaps in the plastic layers allows for folding by a controlled amount in a specified direction, enabling the formation of fairly complex origami structures."

The team uses a maskless lithographic technique based on a digital micromirror array device to spatially pattern the crosslinking of the polymer films, and then dissolves away the uncross-linked regions with a solvent. By directly patterning the polymer films, rather than using a traditional photolithographic approach based on a photoresist layer, it is possible to pattern multiple layers of polymers with widely contrasting material properties using relatively few processing steps, he explains.

In biomedicine or bioengineering, this new approach may help in developing advanced self-deploying implantable medical devices, or in guiding the growth of cells into complex tissues and organs.

The authors feel their data "suggest a clear pathway for future improvements" in the minimum achievable size and maximum achievable complexity of self-folded structures, "simply by using thinner films to enable tighter curvatures, along with improved lithographic methods to allow for patterning of smaller folds."

Instead of following the step-by-step actuation of folds in a controlled sequence characteristic of traditional origami, the new method relies on "collapse" designs, in which all folds are accomplished more or less simultaneously.

"Collapse-type origami designs have not been thoroughly explored in the past because of the difficulty of actuating tens or hundreds of folds with human hands; our technique removes this restriction and we expect that with the actuation scalability provided by our technique, vastly more complex collapsible structures may now be readily explored."

They expect that the new platform they designed will be useful "for future studies addressing fundamental questions about the mechanics of self-folded structures, as well as for applications in microrobotics, biomedical devices and mechanical metamaterials."

Details appear in the current issue of Advanced Materials.