The Moon crossed the Sun’s path on February 17, causing what is known as an annular solar eclipse. The Sun was not covered completely, but the Moon blocked enough of its light to leave a fiery ring. Unless you’re deep in the southern hemisphere, you won’t have noticed.

However, astrologically speaking, eclipses have effects regardless of who is watching. In astrology, an ancient tradition that lacks scientific grounding, eclipses are regarded as being powerful and politically significant celestial events. They are traditionally associated with the destiny of rulers – and some astrologers think Donald Trump is no exception.

Astrologers interpret the meaning of eclipses through horoscopes, celestial maps that locate the Sun, Moon and planets within the 12 signs of the Zodiac that encircle our solar system. During the eclipse, the Sun and Moon were at the edges of the sign Aquarius, a position astrologers associate with endings and shakeups.

This, alongside various other factors including Trump being born during a lunar eclipse in 1946, has led some astrologers to suggest that the eclipse could mark the start of a severe crisis for the US president – even his death.

Predictions like this come around fairly often, and Trump has outlasted many of them before. But these extreme forecasts follow a very old script. For thousands of years, eclipses have been treated as political events, read as omens about kingdoms and their rulers.

Bad omens

Eclipses have been connected with the fate of rulers since at least ancient Mesopotamia, around 4,000 years ago. Keen observers there, in what is now modern-day Iraq, kept lists of phenomena they believed were linked to specific outcomes.

“If a lizard gives birth in the walkway of a house, the household will fall” and “if a white partridge is seen in the city, commercial activity will diminish” are two examples. But one omen has long outlived the others: “if there is an eclipse, the king will die”.

With such high stakes, ancient astronomers invested in systematic observation, record-keeping and calculation to predict eclipses with ever-greater accuracy. This enabled the so-called “substitute king” ritual, where royals tried to avoid their fate by temporarily making someone else king until an eclipse passed.

The link between eclipses and the death of kings spread widely in the ancient world. Egyptian papyri show evidence of this belief, and Greek and Roman history is full of stories connecting eclipses with prominent deaths.

Roman historian Cassius Dio recorded a solar eclipse around the death of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, in AD14, during which “most of the sky seemed to be on fire”. In the gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, the death of Jesus is also marked by darkened Sun.

In the medieval period, when Arabic chroniclers recorded eclipses, they usually noted concurrent deaths of rulers. And in Europe, a solar eclipse in 1133 was so closely associated with the 1135 death of King Henry I of England that it became known as “King Henry’s Eclipse”.

The Antikythera mechanism used rotating concentric rings to calculate eclipses in ancient Greece.

Premodern rulers often hired astrologers to interpret their birth charts – the horoscope cast for the moment they were born. Ideally, the astrologer would pick out an aspect of the chart they could say justified the ruler’s leadership and foretold a long and prosperous reign. This was useful astrological propaganda.

But rulers were less happy when astrologers did this without authorisation – especially if they forecast illness or death. Astrologers were expelled from ancient Rome on numerous occasions for doing just that.

In his book, Lives of the Caesars, Roman historian Suetonius recounted the fate of an astrologer called Ascletarion (or Ascletario). Ascletarion’s predictions of the Emperor Domitian’s imminent downfall in the first century AD prompted the angry emperor to order his execution.

More than 1,400 years later, an astrologer in Oxford was executed for predicting the death of the reigning English monarch, Edward IV. And in 1581, Queen Elizabeth I of England made it a felony to use horoscopes to predict her death or her successor.

Similarly in France, royal pronouncements in 1560, 1579 and 1628 prohibited astrological predictions about princes, states and public affairs. Around the same time, astrologers in Italy got into serious trouble for predicting the deaths of popes.

This was not just a matter of anxiety on the part of rulers. It was also a question of maintaining public order and political stability. State powers were concerned with the ability of astrological predictions to cause general chaos and even prompt protests and rebellions.

They were right to worry. In a time when astrology was taken very seriously, predictions could cause collective panic. During the so-called wars of the three kingdoms, a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in England, Scotland and Ireland, astrologers’ radical political predictions about the fate of the English monarchy fed revolutionary sentiment.

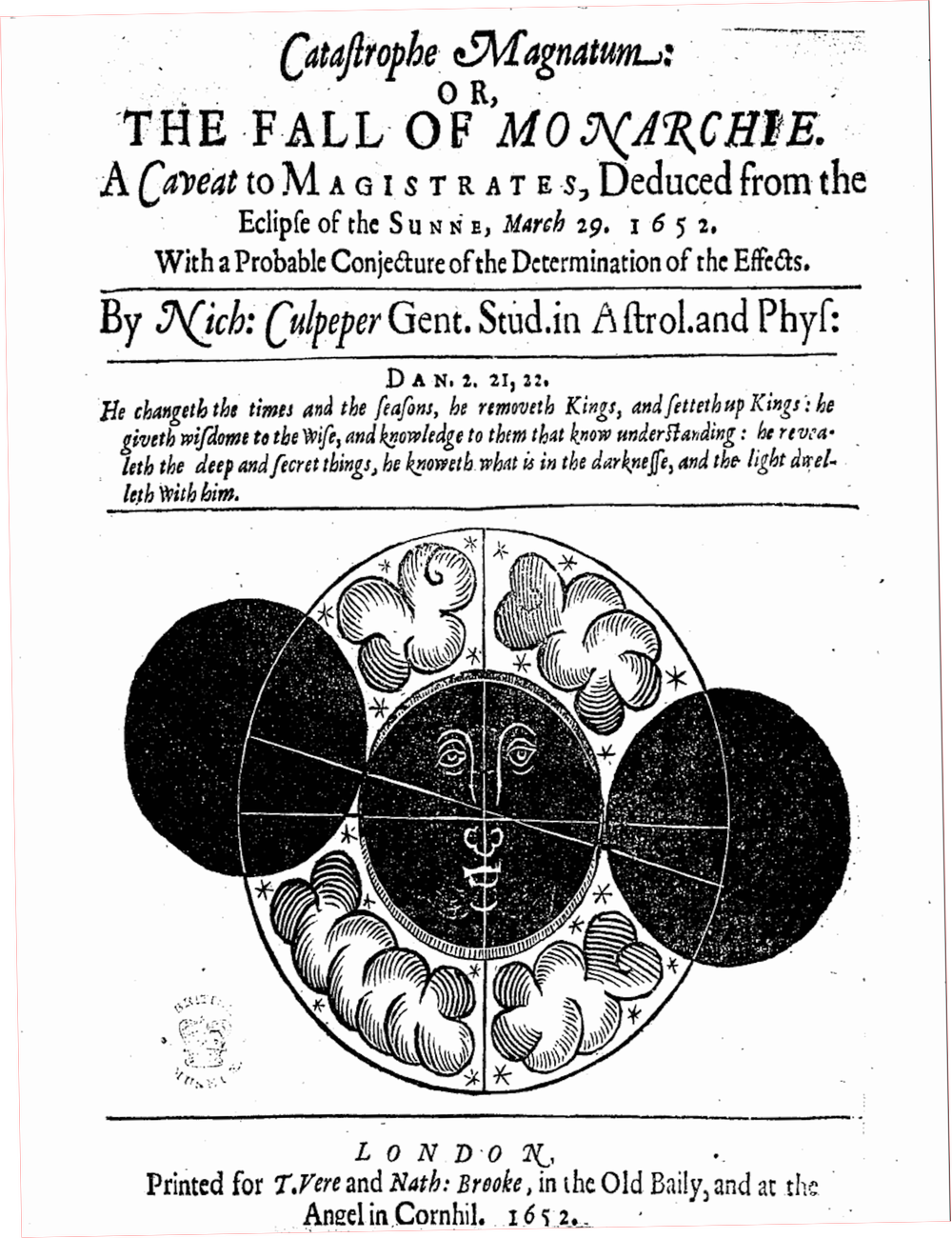

One of these astrologers, Nicholas Culpeper, published predictions of the downfall of all European monarchies on the basis of a solar eclipse in 1652.

Nicholas Culpeper’s Catastrophe Magnatum, an astrological pamphlet written in 1652 about the so-called ‘Black Monday’ solar eclipse that year. Nicholas Culpeper / Catastrophe Magnatum (1652)

Astrology left the world of universities and political courts in the 17th century, but astrologers did not stop making political predictions. In 1790s London, an astrologer called William Gilbert predicted the death of King Gustav III of Sweden. His prophecy was fulfilled a few months later.

And after his attempted assassination in 1981, the then-US president, Ronald Reagan, asked astrologer Joan Quigley whether she could have predicted it. She said yes. Quigley worked for the Reagans for many years, and claimed that she provided advice not just on personal affairs but also on matters of the state, including the best timing to make political announcements.

Although astrology is no longer counted as a science, it remains a player in contemporary politics. Whether or not eclipse predictions come to pass is almost besides the point. Historically, what made eclipses politically dangerous was the speculation often attached to them.

By Michelle Pfeffer, Research Fellow in Early Modern History, University of Oxford. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.