Why was there a sudden drop in the incidence of leprosy at the end of the Middle Ages? To answer this question, biologists and archeologists reconstructed the genomes of medieval strains of the pathogen responsible for the disease, which they exhumed from centuries old human graves. Their results, published in the journal Science, shed light on this obscure historical period and introduce new methods for understanding epidemics.

In Medieval Europe, leprosy was a common disease. The specter of the leper remains firmly entrenched in our collective memory: a person wrapped in homespun cloth, announcing his presence in the streets by ringing a bell. The image is not unfounded. In certain areas it is estimated that nearly one in 30 people were infected with the disease.

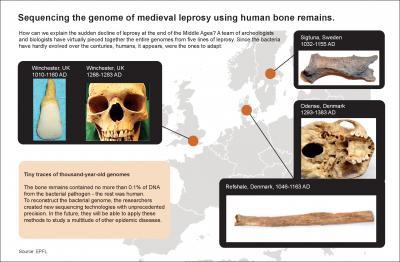

But at the turn of the 16th century, the disease abruptly receded over most of the continent. The event was both sudden and inexplicable. Perhaps the pathogen that causes leprosy had evolved into a less harmful form? To find out, an international team of biologists and archaeologists joined forces. They decoded the nearly complete genomes from five strains of Mycobacterium leprae, the bacterium responsible for leprosy, which they collected and reproduced by digging up the remains of humans buried in medieval graves.

Humans appear to be the ones who adapted to leprosy, causing its decline in Europe.

(Photo Credit: Source: EPFL)

Reconstructing the bacterial genomes was no easy task, as the material available—from old human bones—contained less than 0.1% of bacterial DNA. The researchers developed an extremely sensitive method for separating the two kinds of DNA and for reconstituting the target genomes with an unprecedented level of precision. "We were able to reconstruct the genome without using any contemporary strains as a basis," explains study co-author and EPFL scientist Pushpendra Singh, who worked closely with Johannes Kraus and team from Tubingen University in Germany.

Natural selection in action

The results are indisputable: the genomes of the medieval strains are almost exactly the same as that of contemporary strains, and the mode of spreading has not changed. "If the explanation of the drop in leprosy cases isn't in the pathogen, then it must be in the host, that is, in us; so that's where we need to look," explains Stewart Cole, co-director of the study and the head of EFFL's Global Health Institute.

Many clues indicate that humans developed resistance to the disease. All the conditions were ripe for an intense process of natural selection: a very high prevalence of leprosy and the social isolation of diseased individuals. "In certain conditions, victims could simply be pressured not to procreate," Cole says. "In addition, other studies have identified genetic causes that made most Europeans more resistant than the rest of the world population, which also lends credence to this hypothesis."

Tracing the path of pathogens from Scandinavia to the Middle East

One interesting thing the researchers discovered was a medieval strain of Mycobacterium leprae in Sweden and the U.K. that is almost identical to the strain currently found in the Middle East. "We didn't have the data to determine the direction in which the epidemic spread. The pathogen could have been carried to Palestine during the Crusades. But the process could have operated in the opposite direction, as well."

In addition to the historical significance of the research, the study in Science is important in that it improves our understanding of epidemics, as well as how the leprosy pathogen operates. Sequencing methods designed as part of this research are among the most precise ever developed, and could enable us to track down many other pathogens that are lurking in foreign DNA. In addition, the incredible resistance of Mycobacterium leprae's genetic material – probably due to its thick cell walls – opens up the possibility of going even further back in history to uncover the origins of this disease that still affects more than 200,000 people worldwide each year.