If emission rates continue unchecked, regions of the United States could experience between three and nine additional days per year of unhealthy ozone levels by 2050, according to a new study from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) published in Geophysical Research Letters.

"In the coming decades, global climate change will likely cause more heat waves during the summer, which in turn could cause a 70 to 100 percent increase in ozone episodes, depending on the region," said Lu Shen, first author and graduate student at SEAS.

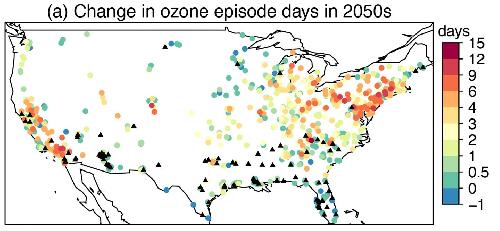

California, the Southwest, and the Northeast would be the most affected, each possibly experiencing up to nine additional days of dangerous ozone levels, with much of the rest of the country experiencing an average increase of 2.3 days.

These are mean changes from 2000-2009 to 2050-2059 in ozone episode days due to climatechange in the RCP4.5 scenario, as calculated using statistically downscaled projections of daily maximum temperatures from 19 CMIP5 models. Credit: Lu Shen/Harvard University

These are mean changes from 2000-2009 to 2050-2059 in ozone episode days due to climatechange in the RCP4.5 scenario, as calculated using statistically downscaled projections of daily maximum temperatures from 19 CMIP5 models. Credit: Lu Shen/Harvard University

This increase could lead to more respiratory illness with especially dangerous consequences for children, seniors, and people suffering from asthma.

"Short-term exposure to ozone has been linked to adverse health effects," said Loretta J. Mickley, a co-author of the study. "High levels of ozone can exacerbate chronic lung disease and even increase mortality rates."

While temperature has long been known as an important driver of ozone episodes, it's been unclear how increasing global temperatures will impact the severity and frequency of surface level ozone.

To address this question, Shen and Mickley -- with coauthor Eric Gilleland of the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) -- developed a model that used observed relationships between temperature and ozone to predict future ozone episodes.

Previous research had not relied so heavily on existing observations, making projections uncertain. Shen and co-authors analyzed ozone-temperature relationships at measurement sites across the US, and found them surprisingly complex.

"Typically, when the temperature increases, so does surface ozone," said Mickley.

"Ozone production accelerates at high temperatures, and emissions of the natural components of ozone increase. High temperatures are also accompanied by weak winds, causing the atmosphere to stagnate. So the air just cooks and ozone levels can build up."

However, at extremely high temperatures -- beginning in the mid-90s Fahrenheit -- ozone levels at many sites stop rising with temperature. The phenomena, previously observed only in California, is known as ozone suppression.

In order to better predict future ozone episodes, the team set out to find evidence of ozone suppression outside of California and test whether or not the phenomena was actually caused by chemistry.

They found that 20 percent of measurement sites in the US show ozone suppression at extremely high temperatures. Their results called into question the prevailing view that the phenomenon is caused by complex atmospheric chemistry.

"Rather than being caused by chemistry, we found that this dropping off of ozone levels is actually caused by meteorology," said Shen. "Typically, ozone is tightly correlated with temperature, which in turn is tightly correlated with other meteorological variables such as solar radiation, circulation and atmospheric stagnation. But at extreme temperatures, these relationships break down."

"This research gives us a much better understanding of how ozone and temperature are related and how that will affect future air quality," said Mickley. "These results show that we need ambitious emissions controls to offset the potential of more than a week of additional days with unhealthy ozone levels."

source: Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences