A new statistical framework

Rethinking the traditional, ad hoc approach, Pedersen and Weng have proposed a new state-space model for analyzing fish movement data collected by marine observation networks. Their new model was recently published in the scientific journal Methods in Ecology and Evolution. Its goal is to quantify the uncertainty associated with this imperfect locating system, and to improve its accuracy.

"Previous methods were not formulated with the fish, ocean and acoustics in mind," said Pedersen. "They therefore do not exploit all available information, such as the biology of the fish limiting its range of possible movement."

Pedersen and Weng's new state-space model for estimating individual fish movement is two-part—one part that models the fish behavior, and one that models the detection of that behavior.

"It tells us how the fish is moving," said Pedersen. "Does the fish swim in straight lines? Does it have a particular home range, or center of attraction, for its movements?"

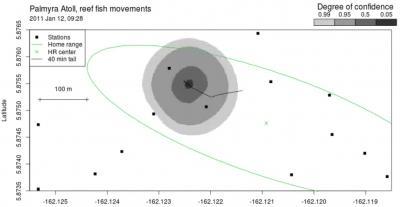

This shows confidence regions (grey contours) for the location of a fish at Palmyra Atoll, along with home range (green line) estimated by the state-space model.

(Photo Credit: Martin W. Pedersen and Kevin C. Weng, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

The second part of the model estimates the likelihood of detecting a fish—incorporating the detection probability, environmental noise, and both presence and absence data. When receivers are located close to each other, it can even help researchers triangulate positions. Acoustic telemetry works in much the same way that cell tower networks pin down the location of your mobile phone: The distance from your phone (or the fish tag) to several cell towers (or acoustic receivers) is measured, and circles of that radius are drawn around each tower (receiver). Where the circles intersect—that's you (or the fish).

The observation model also uses negative data, or the lack of detections, in combination with the behavior model to estimate how far the fish may have traveled while undetected. "Knowing where the fish is not located actually tells you a lot about where it is located, and with our new method, we are able to utilize that information and achieve a better accuracy," Pedersen said.

Does it work in the real (underwater) world?

To field-test their model, the researchers turned to the spectacular tropical reef setting of Palmyra atoll in the central Pacific Ocean—home to myriad fish, sharks, manta rays, whales and turtles.

With monitoring data collected for coral reef fish from 51 underwater observer stations at Palmyra Atoll, Pedersen and Weng used their state-space model to develop contour maps that provided a visual representation of the confidence regions for the locations of the fish over time, along with a home range estimate.

During daylight hours, fish locations were estimated with a 95% confidence region radius of 50 meters, at their most accurate.

By reducing the uncertainties associated with underwater location tracking, Pedersen and Weng hope to provide researchers and marine managers with better information to help support marine conservation activities for reef fish and other threatened species.

"It helps us to better understand how they feed, breed and rest," Weng said. "Ultimately, more accurate movement information will help us to conserve these species."

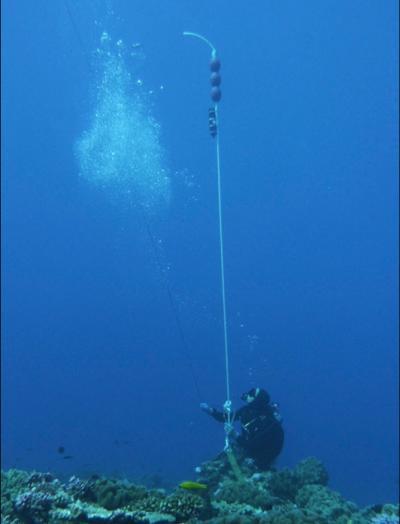

University of Hawaii at Manoa scientists have developed a new method of estimating fish movements underwater. Their new state-space model for analyzing fish movement data collected by marine observation networks aims to quantify the uncertainty associated with this imperfect locating system, and to improve its accuracy.

(Photo Credit: Martin W. Pedersen and Kevin C. Weng, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

University of Hawaii at Manoa scientists Martin W. Pedersen and Kevin C. Weng have proposed a new state-space model for analyzing fish movement data collected by marine observation networks.

(Photo Credit: Kevin C. Weng, University of Hawaii at Manoa)

Source: University of Hawaii at Manoa