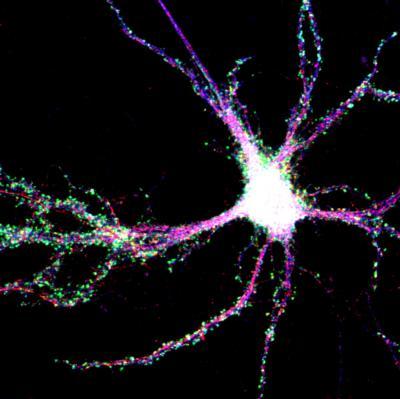

Increasing the amount of SUMO, a small protein in the brain, could be a way of treating diseases such as epilepsy and schizophrenia, reveal scientists at the University of Bristol, UK. Their findings are published online today in Nature. Distribution of kainate receptors (blue) and SUMOylation enzymes (red) in the synaptic areas (green) of a hippocampal neurone. Credit: Stephane Martin

Distribution of kainate receptors (blue) and SUMOylation enzymes (red) in the synaptic areas (green) of a hippocampal neurone. Credit: Stephane Martin

The brain contains about 100 million nerve cells, each having 10,000 connections to other nerves cells. These connections, called synapses, chemically transmit the information that controls all brain function via proteins called receptors. These processes are believed to be the basis of learning and memory.

A major feature of a healthy brain is that the synapses can modify how efficiently they work, by increasing or decreasing the amount of information transmitted. In disorders such as epilepsy the synapses transmit too much information, resulting in over-excitation in the cells.

The research team, led by Professor Jeremy Henley at Bristol University, has discovered that when one type of receptor – the kainate receptor – receives a chemical signal, a small protein called SUMO becomes attached to it. SUMO pulls the kainate receptor out of the synapse, preventing it from receiving information from other cells, thus making the cell less excitable.

Professor Henley said: “This work is important because it gives a new perspective and a deeper understanding of how the flow of information between cells in the brain is regulated. It is possible that increasing the amount of SUMO attached to kainate receptors – which would reduce communication between the cells – could be a way to treat epilepsy by preventing over-excitation.”

The discovery that SUMO proteins can regulate the way brain cells communicate may provide insight into the causes of, and treatments for, brain diseases that are characterised by too much synaptic activity. This discovery also provides new potential targets for drug development that could one day be used to treat a range of such disorders.

Source: University of Bristol.