Necrotizing enterocolitis is an intestinal disease that afflicts about one in ten extremely premature infants and is fatal in nearly one-third of cases. The premature infant gut is believed to react to colonizing bacteria, causing damage to the intestinal walls and severe infection. In a study appearing March 17 in Cell Reports, researchers describe an association between necrotizing enterocolitis and a subset of E. coli bacteria, called uropathogenic E. coli, that colonize the infant gut.

"We found a significant correlation with necrotizing enterocolitis," says co-first author Doyle Ward, a microbiologist at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. "This is a challenging and complicated disease, and I think that any new information that offers an opportunity to save an infant's life is an important advance."

Uropathogenic E. coli, or UPEC--typically the cause of urinary tract infections--is frequently found in the gut of infants and adults. But according to the new study, when UPEC colonize the gut of extremely premature infants, those infants have a higher risk of developing necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). "There's nothing to indicate that these pre-term infants are encountering different bacteria than term infants," says Ward. "It's just that they may be uniquely vulnerable to certain bacteria."

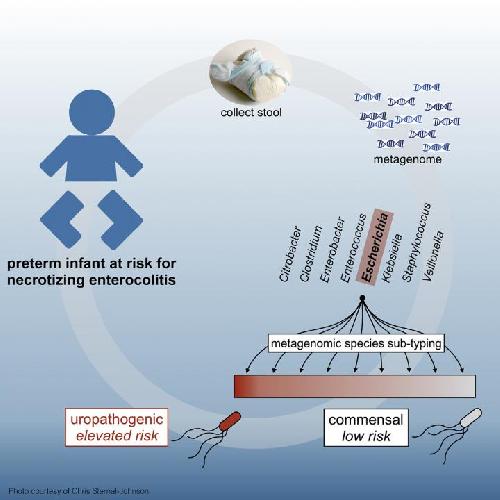

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) afflicts approximately 10 percent of extremely preterm infants with high fatality. Aberrant intestinal colonization has been suspected to contribute to disease. This visual abstract shows how Ward et al. apply metagenomic approaches to define the microbiota of the preterm infant gut and implicate uropathogenic E. coli as a risk factor for NEC and death. Credit: Ward and Scholz et al./Cell Reports 2016

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) afflicts approximately 10 percent of extremely preterm infants with high fatality. Aberrant intestinal colonization has been suspected to contribute to disease. This visual abstract shows how Ward et al. apply metagenomic approaches to define the microbiota of the preterm infant gut and implicate uropathogenic E. coli as a risk factor for NEC and death. Credit: Ward and Scholz et al./Cell Reports 2016

The researchers collaborated with hospitals in Cincinnati, Ohio, and Birmingham, Alabama, to obtain stool samples from a cohort of 166 infants: 144 pre-term and 22 that had been carried to term. The team sequenced the infants' stool and developed metagenomic analysis tools to identify the bacteria colonizing each infant. Previous work had already identified Enterobacteriaceae--a family of bacteria that includes E. coli--as potentially associated with NEC, but Ward and his colleagues used new analysis tools to distinguish the different types of E. coli in the infants.

The team singled out UPEC as the E. coli type most strongly linked to infants who developed NEC. In the study cohort, 27 of the infants developed NEC, all pre-term. The disease was fatal in 15 of those cases. UPEC was found in 44 percent of the infants who developed NEC, compared to only 16 percent of the 111 infants who survived without developing NEC.

"Our study suggests that if you can quickly identify UPEC in the microbiome of a pre-term infant, you can know that the infant has a greater risk for NEC before there are any symptoms" says Ward.

Although the team didn't address the question of where UPEC in an infant's gut might originate, they did observe an association between vaginal delivery and death from NEC in these extremely pre-term infants. "Many infants do have UPEC in their gut," says Ward. "It may be that they're colonized when they pass through the birth canal, and this could be a source of risk. We just don't know yet." But Ward strongly cautions against making such generalizations from one cohort, adding that more work is needed. "It's important to realize that infants also acquire many beneficial bacteria from their mothers during vaginal birth--and it's likely that the good bacteria have a role in preventing NEC. We're still at a basic research stage."

"The take-home message is that if we can identify these organisms early enough in a pre-term infant, and learn about them in advance, we can arm physicians with information that could help them make care decisions for these vulnerable infants," Ward says.

source: Cell Press