DURHAM, N.C. -- Antibiotic-resistant infections are a growing threat to public health, striking about 2 million Americans each year and killing at least 23,000 of them. Microbes are rapidly evolving resistance to existing drugs, making the need for newer, more potent antibiotics greater than ever.

Now, researchers have discovered the structure of a well-established target for antibiotic development, an enzyme called MraY, as it is bound to the natural antibacterial muraymycin. The results show that the enzyme dramatically changes its shape to reveal a hidden binding pocket, which muraymycin connects to like a two-pronged plug inserting into a socket.

The study, published April 18, 2016 in Nature, provides important structural information for designing broad-spectrum antibiotics that target an enzyme essential to every known strain of bacteria, including those that cause tuberculosis and MRSA.

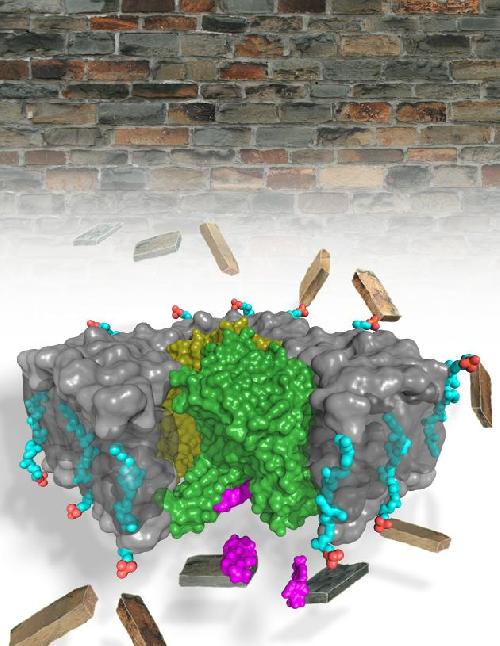

A schematic portraying the structure of MraY (in green and brown), an essential enzyme in bacterial cell wall synthesis. The enzyme is bound to the antibiotic muraymycin (magenta) which is overlaid on an image of a brick wall that symbolizes the bacterial cell wall. Drugs that bind MraY can inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis. Credit: Ben Chung

A schematic portraying the structure of MraY (in green and brown), an essential enzyme in bacterial cell wall synthesis. The enzyme is bound to the antibiotic muraymycin (magenta) which is overlaid on an image of a brick wall that symbolizes the bacterial cell wall. Drugs that bind MraY can inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis. Credit: Ben Chung

"Nature has evolved a number of ways to inhibit this enzyme, but researchers haven't been able to mimic their properties in the laboratory," said senior study author Seok-Yong Lee, Ph.D., assistant professor of biochemistry at Duke University School of Medicine. "Here, we provide a platform for understanding how these natural inhibitors work, with the degree of molecular detail necessary to accelerate drug development."

Many of the most widely used antibiotics were derived from substances concocted by soil-dwelling bacteria and fungi to poison their microbial competitors. The discovery of these natural products led some leaders in the scientific community to announce an end to infectious diseases, but those predictions proved premature as more stubborn, drug-resistant forms of bacteria emerged. But rather than keeping up with the need, antibiotic development has stagnated in recent decades. The World Health Organization now warns that society is on the cusp of a post-antibiotic era, where millions of people could die from previously curable diseases.

Structural biology provides a glimmer of hope. By capturing the interactions between bacteria and their natural killers, Lee believes that he can provide the inspiration for developing new and improved drugs. For instance, five different naturally-occurring antibiotics target MraY, an enzyme responsible for building up the cell wall to shield bacteria from outside attack. However, without knowing the structures involved, researchers have been unable to develop drugs with the same effects.

Almost three years ago, Lee solved the atomic structure of MraY. The finding, which was published in the journal Science, represented a critical first step to understanding how to disable the bacterial enzyme.

In this study, Lee took the next step by visualizing the structure of MraY while it was locked in an embrace with the natural antibiotic muraymycin. He used a tool known as X-ray crystallography to generate an atomic level three-dimensional picture of this complex. When Lee compared the structures of MraY on its own versus when it was bound by muraymycin, he was surprised to find they were quite different. The enzyme essentially changed its shape to accommodate its inhibitor.

"This is not the relationship that we typically see between enzymes and their substrates or inhibitors," Lee said. "We usually think of the lock and key model, where there is a clearly defined shape for the inhibitor that fits into a corresponding shape on the surface of the enzyme. Instead, we found that this enzyme undergoes a dramatic conformational change upon binding to this inhibitor to expose a binding pocket that was not apparent before."

Lee used various molecular biology and biochemistry techniques to figure out which interactions were important to maintain the connection between MraY and its inhibitor. Basically, he found that muraymycin connects to the once-hidden pocket like a two-pronged plug inserting into a childproof outlet. Next, Lee plans to repeat the same experiments with other inhibitors of MraY.

"Many natural product inhibitors bind and inhibit this enzyme in a different way, by a different mechanism," he said. "If we understand every possible mechanism of inhibition of this enzyme, then we may be able to translate that knowledge into the development of drugs that can target it with the most specificity."

source: Duke University