(Santa Barbara, Calif.) –– Studies of the small sea squirt may ultimately help solve the problem of rejection of organ and bone marrow transplants in humans, according to scientists at UC Santa Barbara.

An average of 20 registered patients die every day waiting for transplants, due to the shortage of matching donor organs. More than 110,000 people are currently waiting for organ transplants in the U.S. alone. Currently, only one in 20,000 donors are a match for a patient waiting for a transplant.

These grim statistics drive scientists like Anthony W. De Tomaso, assistant professor of biology at UCSB, to delve into the cellular biology of immune responses. His studies of the sea squirt shed light on the complicated issue of organ rejection. The latest results are published online today in the journal Immunity.

De Tomaso hopes to understand how it might be possible to "tune" the body's immune response in order to dial down the rejection of a donated organ. Studying cellular responses in simple organisms may also eventually help with autoimmune diseases –– those in which the body mistakenly attacks itself.

Botryllus schlosseri is a type of sea squirt.

(Photo Credit: Anthony W. De Tomaso)

"Right now, when you get a transplant, you're usually on immunosuppressives your whole life," said De Tomaso. "And that's like sort of kicking your immune system in the teeth. What if we could raise the threshold of when you would respond, instead of just shutting the whole system off?"

De Tomaso and his research team study Botryllus schlosseri, a type of sea squirt. This small organism –– known as a tunicate because of its covering, or "tunic" –– is a modern day descendant of the vertebrate ancestor, the group to which we belong. Tunicates begin life as swimming tadpoles with primitive backbones, nerves, and musculature that are similar to all vertebrates, but soon transform into stationary creatures. Tunicates latch onto intertidal surfaces and look like flat flowers –– with each "petal" being a separate, but genetically identical, body.

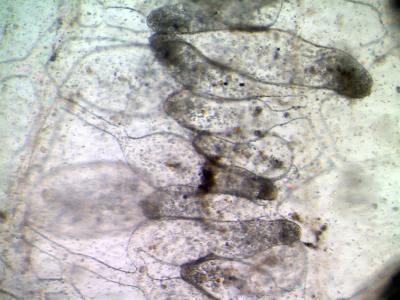

De Tomaso focuses on what happens when one sea squirt lands next to another. In this case, cells in the sea squirt's fingerlike edges, or "ampullae," recognize the neighboring sea squirt as "self" or "non-self." When the other sea squirt is related, then the two colonies fuse; otherwise, they reject each other. De Tomaso was involved in identifying the gene controlling the choice between fusion and rejection in the sea squirt when he was a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University

The fusing of two sea squirtsat their fingerlike edges is called ampullae.

(Photo Credit: Anthony W. De Tomaso)

In his current research, De Tomaso studies how the signals on the surface of the sea squirt's cells get translated inside the circuitry of the cell, where the final decision about acceptance or rejection is made. "In the case of Botryllus, what we found is that we have the same kind of integration that goes on in humans, but instead of having a multiple, very complex set of inputs coming in, we only have two," said DeTomaso. "We have also found that we can manipulate each one independently, so we know that somehow they are put together and the two inputs are integrated, and a decision is made about how to respond."

De Tomaso explained that he decided to work on Botryllus because it has a unique way to answer a very complicated question. He hopes to understand the process of rejection or acceptance. "If we could manipulate that process," said Tomaso, "then we could basically teach the immune system to simply ignore certain things. We could say, 'Just don't respond to this. We're going to transfer this bone marrow, just don't kill this bone marrow.' Bone marrow could get in and start making new blood, and it would be fine. To me, that's the most exciting thing long-term for the work."

Tanya R. McKitrick and Anthony W. De Tomaso are in De Tomaso's lab, which pumps in sea water from the ocean to keep the sea squirts alive.

(Photo Credit: George Foulsham, Office of Public Affairs, UCSB)