Washington, D.C.—Here on Earth we worry about our planet's atmosphere warming by a few degrees on average over the next century, and even weather fronts bring temporary changes in temperature of no more than tens of degrees. Now astronomers writing in the January 29 Nature report on an extra-solar planetary system where global warming is taken to a spectacular extreme: a 700 degree rise in a few hours.

The planet, known as HD 80606b, is a gas giant orbiting a star 200 light-years from Earth. Its extremely eccentric orbit around the star takes it from a relatively comfortable distance approximating the Earth's orbit, to the blazing hot regions much closer than Mercury is to our Sun. Infrared sensors aboard NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope measured the planet's temperature as it swooped close to the star, observing a planetary heat wave that rose from 800 to 1,500 degrees Kelvin (980 to 2,240 degrees Fahrenheit) in just six hours.

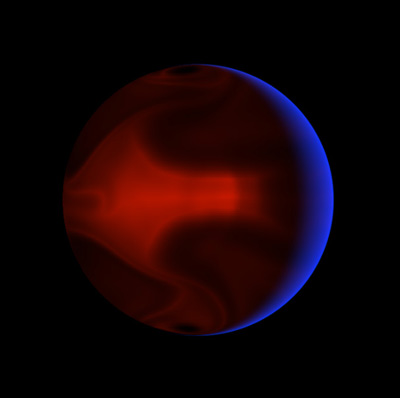

The planet HD80606b glows orange from its own heat in this computer-generated image. A massive storm has formed in response to the pulse of heat delivered during the planet's close swing past its star. The blue crescent is reflected light from the star. Image by D. Kasen, J. Langton, and G. Laughlin (UCSC).

"This is the first time that we've detected weather changes in real time on a planet outside our solar system," says lead author Greg Laughlin of the Lick Observatory, University of California at Santa Cruz. "The results are very exciting because they give us important clues to the atmospheric properties of the planet."

"Even after finding nearly 200 planets, the diversity and oddness of these new worlds continues to amaze and confound me," says Paul Butler of the Carnegie Institution for Science's Department of Terrestrial Magnetism. Butler made the precision velocity measurements of the host star that allowed the planet's orbit to be calculated. Butler's work has uncovered about half of the known extra-solar planets.

The precision of the velocity measurements was crucial for this experiment. Observations from the infrared space telescope had to be centered on the time that the planet passed behind the star, known as the secondary eclipse. The disappearance of the planet during the secondary eclipse allowed the measurements to be calibrated and the planet's temperature to be determined.

HD8606b has an estimated mass of about four times that of Jupiter and completes its orbit in about 111 days. At its closest approach to the star it experiences radiation about 800 times stronger than when it is most distant.

The planet is expected to pass in front of its star when viewed from Earth on February 14, 2009, and may possibly transit the star, an event that is eagerly anticipated by both professional and amateur astronomers.

Source: Carnegie Institution