The superlattice was studied first using quantum-mechanical molecular dynamics simulations conducted in Landman's lab. The system was also studied experimentally by a research group headed by Terry Bigioni, an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Toledo.

The unusual behavior occurred as the superlattice was being compressed using hydrostatic techniques. After the structure had been compressed by about six percent of its volume, the pressure required for additional compression suddenly dropped significantly. The researchers discovered that the drop occurred when the nanocrystal components rotated, layer-by-layer, in opposite directions.

Just as the hydrogen bonds direct how the superlattice structure is formed, so also do they guide how the structure moves under pressure.

"The hydrogen bond likes to have directionality in its orientation," Landman explained. "When you press on the superlattice, it wants to maintain the hydrogen bonds. In the process of trying to maintain the hydrogen bonds, all the organic ligands bend the silver cores in one layer one way, and those in the next layer bend and rotate the other way."

When the nanoclusters move, the structure pivots about the hydrogen bonds, which act as "molecular hinges" to allow the rotation. The compression is possible at all, Landman noted, because the crystalline structure has about half of its space open.

The movement of the silver nanocrystallites could allow the superlattice material to serve as an energy-absorbing structure, converting force to mechanical motion. By changing the conductive properties of the silver superlattice, compressing the material could also allow it be used as molecular-scale sensors and switches.

The combined experimental and computation study makes the silver superlattice one of the most thoroughly studied materials in the world.

"We now have complete control over a unique material that by its composition has a diversity of molecules," Landman said. "It has metal, it has organic materials and it has a stiff metallic core surrounded by a soft material."

For the future, the researchers plan additional experiments to learn more about the unique properties of the superlattice system. The unique system shows how unusual properties can arise when nanometer-scale systems are combined with many other small-scale units.

"We make the small particles, and they are different because small is different," said Landman. "When you put them together, having more of them is different because that allows them to behave collectively, and that collective activity makes the difference."

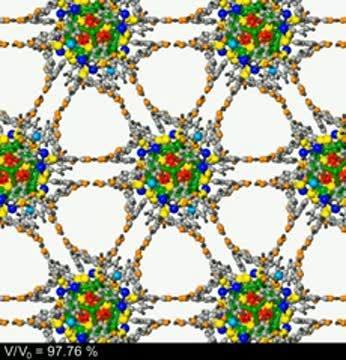

This video shows the motion of nanoparticles in neighboring layers of the superlattice as pressure is applied.

(Photo Credit: Courtesy of Uzi Landman)

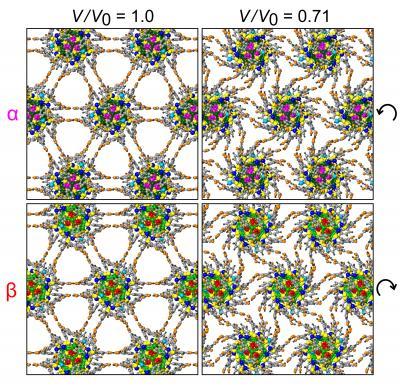

This figure shows the arrangement of nanoparticles in two neighboring layers of the superlattice, with configurations on the left corresponding to the equilibrium state of the superlattice at ambient conditions, and the ones on the right recorded at the end of the volume compression process. Comparison of the configurations reveals flexure of the ligands and gear-like rotations of the nanoparticles, with the hydrogen-bonds between ligands anchored to adjacent nanoparticles serving as "molecular hinges."

(Photo Credit: Courtesy Uzi Landman)

Source: Georgia Institute of Technology