In a famous experiment first performed more than 220 years ago, Italian physician Luigi Galvani discovered that the muscles of a frog's leg twitch when an electric voltage is applied. An international group of scientists from Italy, the UK and France has now brought this textbook classic into the era of nanoscience. They used a powerful new synchrotron X-ray technique to observe for the first time at the molecular scale how muscle proteins change form and structure inside an intact and contracting muscle cell. The results are published in the 11 April 2011 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

The team included scientists from Università di Firenze (Italy), King's College London (UK) and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble (France).

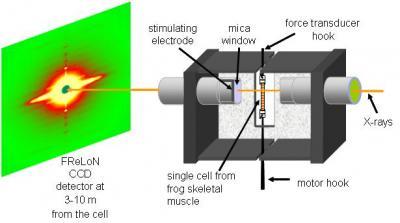

This is the set-up of the experiment at the ESRF where a powerful synchrotron X-ray technique was used to observe for the first time at the molecular scale how muscle proteins change form and structure inside an intact and contracting muscle cell.

(Photo Credit: V. Lombardi, Florence University)

A muscle cell contains two sets of filaments composed of the proteins actin and myosin, respectively. Muscles contract as a result of the relative sliding of these filaments. When the brain sends a nerve signal to activate a muscle, the electrical signal is transmitted to the muscle cell. This sets off a chain of events inside the muscle cell that eventually leads to changes in the structure of the myosin and actin filaments.

But what exactly happens during this process at the molecular level?. "As we need muscles for locomotion, breathing and body posture, and for the contraction of the heart, understanding of these mechanisms has broad significance in biology and medicine", says Malcolm Irving from King's College London.

"Studying a single intact and contracting muscle cell at the molecular scale in milliseconds became possible thanks to a new technique called X-ray interferometry based on low angle diffraction. This requires the extremely intense and narrow beam of X-rays provided by the ESRF", adds Theyencheri Narayanan from the ESRF, a co-author of the paper.

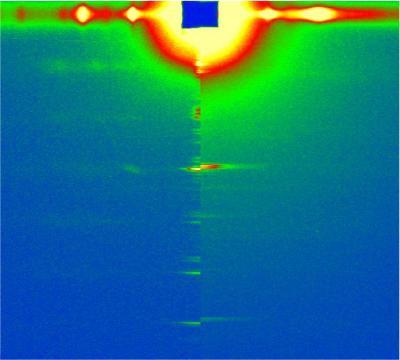

This is a composite image made from two low-angle diffraction data sets, one taken with muscle fibers at rest (left), and the other with muscle fibers under isometric contraction (right). The color corresponds to the intensity of the X-rays scattered elastically at a very small angle. From the changes, the conformation of the molecular motors is computed.

(Photo Credit: V. Lombardi, Florence University)

The results of the experiment reveal the conformation of the head domains of myosin—the molecular motors that drive filament sliding—in resting muscle, and show that the movements of the myosin motors following muscle activation are much slower than the structural changes in the actin filaments. The different timings of the structural changes reveal the signalling pathway between the actin and myosin filaments in muscle, shedding new light on the mechanism of muscle regulation.

"We were observing quite rapid biological processes, in the order of milliseconds, along with minuscule structural changes, typically 10 nm or less. A human hair is ten-thousand times thicker. To integrate the mechanical and X-ray diffraction methods that are required to resolve the combination of these extremes is a real experimental challenge", explains Vincenzo Lombardi from the Unversity of Florence.

Although the study has no immediate clinical application, its longer-term impact may be in the area of heart disease, in which these fundamental signalling mechanisms are not working optimally in the heart muscle. Existing drugs to treat heart failure by modulating this signalling pathway are far from ideal. "To develop better drugs for heart failure, it's likely that a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of muscle regulation is needed, and that may be the long-term contribution of our experiments," concludes Malcolm Irving.

This is a view at the movable detector in the ESRF beamline ID02 for small-angle scattering studies. The detector is at the far end of the long, hollow tube. Beamline scientist Theyencheri Narayanan watches from the left.

(Photo Credit: P. Ginter/ESRF)