We may joke about looking for a needle in a haystack, but that's nothing compared to searching for stardust in a foil! A new paper published in Science reveals that such work has led to the discovery of seven dust particles that are not only out of this world, they're out of this solar system.

The Stardust Interstellar Dust Collector was launched in 1999 in an effort to collect contemporary interstellar dust—dust that has travelled to our solar system from another. The Collector returned in 2006; since then scientists have been combing through blue aerogel and aluminum foil collectors looking for microscopic pieces of the dust.

As the Collector flew through space, tiny particles of both stardust and the Wild 2 comet flew into the particle catcher. Much like a bullet through an object, the dust leaves tiny tracks in the aerogel. The foils were left with tiny craters, again leading to possible stardust.

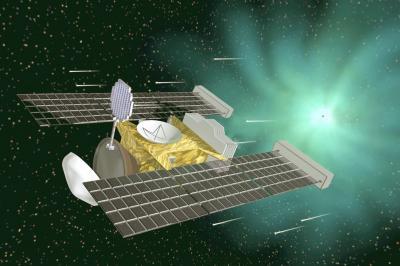

This is an artist rendering of the Stardust Interstellar Dust Collector in space.

(Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The consortium of nearly 70 scientists and a host of citizen scientists have identified seven tiny pieces, each about 200 nanometers to 2 micrometers, identified as interstellar dust. This is the first time contemporary stardust has been identified and studied here on Earth—prior to this, researchers were only able to study through astronomical observations. Philipp Heck, PhD, The Field Museum's Robert A. Pritzker Associate Curator of Meteoritics and Polar Studies explains "contemporary" stardust does not survive longer than a few hundred million years—studies on this stardust can help illuminate change over time, when compared to presolar grains that are older than 4.6 billion years. "For the first time we are examining recent extrasolar material in our labs, this is truly exciting!" said Heck.

Field Museum scientists Heck and Asna Ansari contributed to the study by scanning two foils from the Collector in the Museum's Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) and then examining each of the thousands of images for small craters in the foil. The foils, each 1.4 to 4.2 cm long and only 0.2 cm wide, took two years to examine and evaluate. While the high resolution images revealed several crater candidates, further chemical analysis was required in order to determine the make-up of the particles. "Most craters turned out to be debris from the spacecraft itself, revealed by components of glass and paint," explained Heck. However, four of the 25 craters identified were determined to be interstellar craters.

Now that the seven samples found in both the foil and aerogel have been determined to be contemporary interstellar stardust, new methods are being developed to extract more information out of them. The consortium's study is outlined in more detail in an additional 12 papers, to be published next week in Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

Source: Field Museum