Menlo Park, Calif. -- Scientists working at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory have created the shortest, purest X-ray laser pulses ever achieved, fulfilling a 45-year-old prediction and opening the door to a new range of scientific discovery.

The researchers, reporting today in Nature, aimed SLAC's Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS) at a capsule of neon gas, setting off an avalanche of X-ray emissions to create the world's first "atomic X-ray laser."

"X-rays give us a penetrating view into the world of atoms and molecules," said physicist Nina Rohringer, who led the research. A group leader at the Max Planck Society's Advanced Study Group in Hamburg, Germany, Rohringer collaborated with researchers from SLAC, DOE's Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and Colorado State University.

"We envision researchers using this new type of laser for all sorts of interesting things, such as teasing out the details of chemical reactions or watching biological molecules at work," she added. "The shorter the pulses, the faster the changes we can capture. And the purer the light, the sharper the details we can see."

The new atomic X-ray laser fulfills a 1967 prediction that X-ray lasers could be made in the same manner as many visible-light lasers – by inducing electrons to fall from higher to lower energy levels within atoms, releasing a single color of light in the process. But until 2009, when LCLS turned on, no X-ray source was powerful enough to create this type of laser.

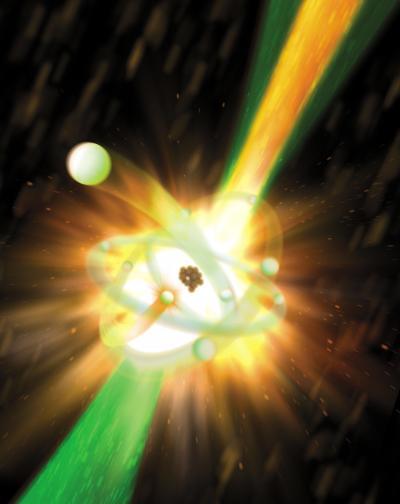

This artist's conception illustrates how the new atomic hard X-ray laser is created.

A powerful X-ray laser pulse from SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory's Linac Coherent Light Source comes up from the lower-left corner (shown as green) and hits a neon atom (center). This intense incoming light energizes an electron from an inner orbit (or shell) closest to the neon nucleus (center, brown), knocking it totally out of the atom (upper-left, foreground). In some cases, an outer electron will drop down into the vacated inner orbit (orange starburst near the nucleus) and release a short-wavelength, high-energy (i.e., "hard") X-ray photon of a specific wavelength (energy/color) (shown as yellow light heading out from the atom to the upper right along with the larger, green LCLS light).

X-rays made in this manner then stimulate other energized neon atoms to do the same, creating a chain-reaction avalanche of pure X-ray laser light amplified by a factor of 200 million.

While the LCLS X-ray pulses are brighter and more powerful, the neon atomic hard X-ray laser pulses have one-eighth the duration and a much purer light color. This new laser will enable more precise investigations into ultrafast processes and chemical reactions than had been possible before, ultimately opening the door to new medicines, devices and materials.

(Photo Credit: Illustration by Gregory M. Stewart, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory)

To make the atom laser, LCLS's powerful X-ray pulses – each a billion times brighter than any available before – knocked electrons out of the inner shells of many of the neon atoms in the capsule. When other electrons fell in to fill the holes, about one in 50 atoms responded by emitting a photon in the X-ray range, which has a very short wavelength. Those X-rays then stimulated neighboring neon atoms to emit more X-rays, creating a domino effect that amplified the laser light 200 million times.

Although LCLS and the neon capsule are both lasers, they create light in different ways and emit light with different attributes. The LCLS passes high-energy electrons through alternating magnetic fields to trigger production of X-rays; its X-ray pulses are brighter and much more powerful. The atomic laser's pulses are only one-eighth as long and their color is much more pure, qualities that will enable it to illuminate and distinguish details of ultrafast reactions that had been impossible to see before.

"This achievement opens the door for a new realm of X-ray capabilities," said John Bozek, LCLS instrument scientist. "Scientists will surely want new facilities to take advantage of this new type of laser."

For example, researchers envision using both LCLS and atomic laser pulses in a synchronized one-two punch: The first laser triggers a change in a sample under study, and the second records with atomic-scale precision any changes that occurred within a few quadrillionths of a second.

In future experiments, Rohringer says she will try to create even shorter-pulsed, higher-energy atomic X-ray lasers using oxygen, nitrogen or sulfur gas.