Despite the scientific interest, there was little progress in finding the particle until 2001 when the physicist Alexei Kitaev (now a professor at the University of California-Santa Barbara) predicted that, under the correct conditions, a Majorana fermion would appear at each end of a superconducting wire. Superconductivity is the phenomenon when a material can carry electricity without any resistance. In Kitaev's prediction, inducing some types of superconductivity would cause the formation of Majoranas. These emergent particles are stable and do not annihilate each other (unless the wire is too short) because they are spatially separated. Importantly, Kitaev also outlined how such a particle could be harnessed as a qubit, the basis of a quantum computer, which added significant impetus to the search.

In 2012, a team of researchers at the Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands may have caught a glimpse of Majorana fermions in an experiment that induced superconductivity in a semiconductor known as indium antemonide. They reported very strong evidence for the electrical signal characteristic of a neutral Majorana in nanoscale wires made of these materials.

Scientists, however, have argued that other phenomena could produce the same signal, and Yazdani and his team sought to find more definitive observation of Majorana fermions by capturing an image of them. In 2013, Yazdani and Andrei Bernevig, an associate professor of physics, teamed up to propose a new approach for how the Majorana particle could occur in materials that combine magnetism and superconductivity. They also proposed that such a particle could be directly observed using a device called a scanning-tunneling microscope.

Yazdani and Bernevig received funding to carry out their proposed experiments through the Princeton Center for Complex Materials, an interdisciplinary center on campus funded by the National Science Foundation. Promising results from that work allowed them to partner with the Texas team and win a $3 million grant from the Office of Naval Research under a program called the Majorana Basic Research Challenge.

The setup they created starts with an ultrapure crystal of lead, whose atoms naturally line up in alternating rows that leave atomically thin ridges on the crystal's surface. The researchers then deposited pure iron into one of these ridges to create a wire that is just one atom wide and about three atoms thick. Considering its narrow width, this wire is very long — if it were a pencil it would be five feet from tip to eraser.

The researchers then placed the lead and the embedded iron wire under the scanning-tunneling microscope and cooled the system to -272 degrees Celsius, just a degree above absolute zero. After about two years of painstaking work, they confirmed that superconductivity in the iron wire matched the conditions required for Majorana fermion to be created in their material.

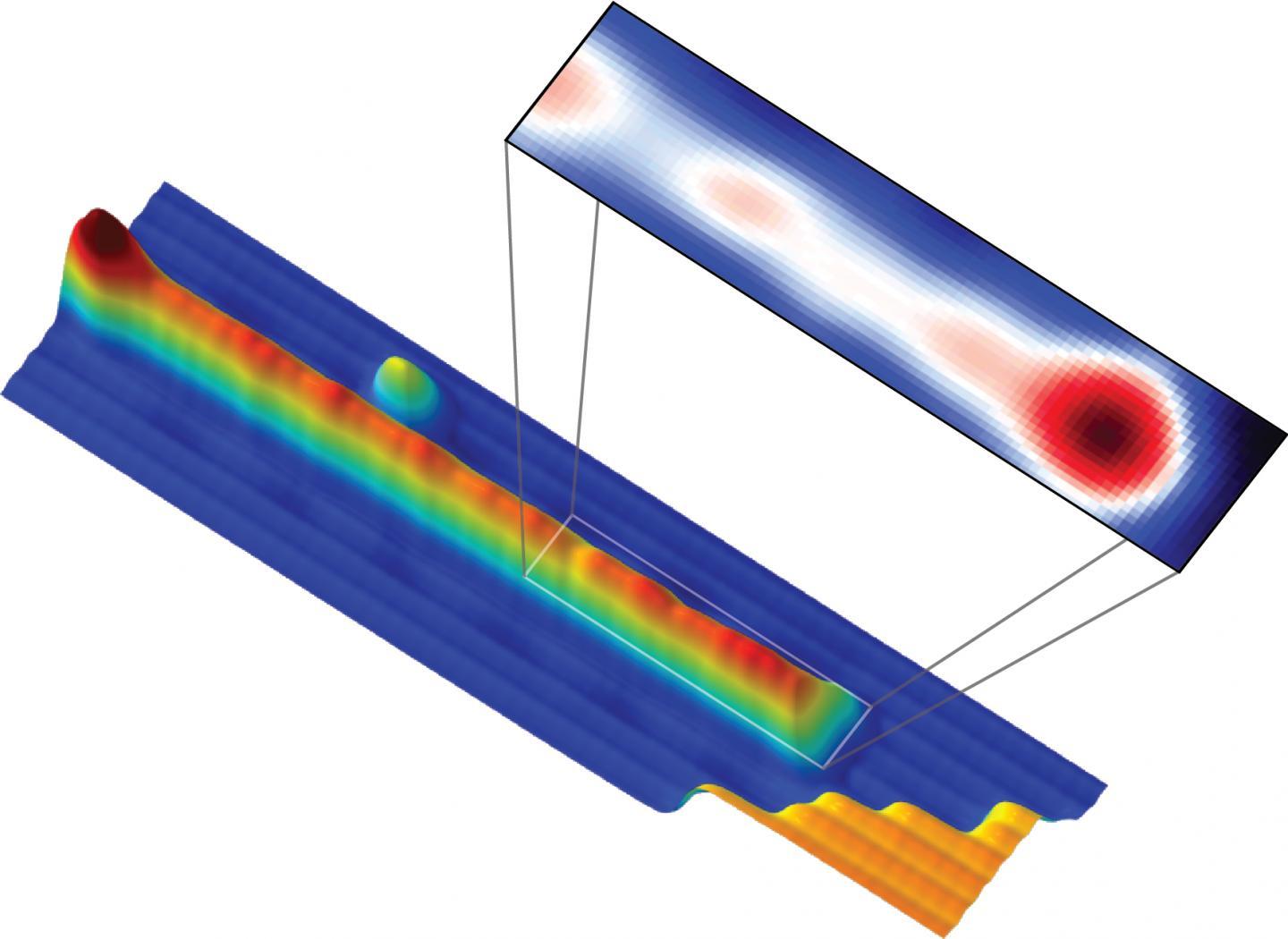

Ultimately, the microscope was also able to detect an electrically neutral signal at the ends of the wires, similar to those seen in the Delft experiment. However, the setup also allowed the researchers to directly visualize how the signal changes along the wire, essentially mapping the quantum probability of finding the Majorana fermion along the wire and pinpointing that it appears at the ends of the wire.

"It shows that this signal lives only at the edge," Yazdani said. "That is the key signature. If you don't have that, then this signal can exist for many other reasons."

Yazdani noted that although the experimental setup used to measure and demonstrate the existence of Majorana particle is very complex, the new approach does not use exotic materials and is straightforward for other scientists to reproduce and use.

"What's very exciting is that it is very simple: it is lead and iron," he said.

In fact, in the course of their experiments the researchers found that their approach is even easier to use than they expected. While they set out to fine-tune the properties of their materials to exact specifications, they found that their system is almost guaranteed to have Majorana fermions, as long as some general features of magnetism and superconductivity are in place. Calculations performed by the Austin team led by Professor Allan MacDonald have confirmed this picture.

"The details turned out to be not that important," Yazdani said.

Bernevig added, "As long as you have a strong magnetic material — like iron but it could be other magnets — in which electrons are magnetically polarized (or electrons feel a very strong magnetic field), the possible range of parameters in which Majoranas appear increases dramatically."

In previous proposals, the appearance of Majoranas would only happen under a narrow range of conditions. Typically, it is hard to have superconductivity and magnetism in the same material — magnetic fields usually kill superconductivity. But in the Princeton team's method, the magnetic field is present only where it is needed, on the wire, so superconductivity creeps in from the underlying lead unimpeded.

"Once you have that, all you need are some relativistic effects that are easy to induce at the surface of a heavy element like lead, and the Majoranas will appear," Bernevig said. "We expect many more materials will produce these elusive particles."

Princeton University researchers first deposited iron atoms onto a lead surface to create an atomically thin wire. They then used a scanning-tunneling microscope to create a magnetic field and to map the presence of a neutral signal that indicates the presence of Majorana fermions, which appeared at the ends of the wire.

(Photo Credit: Ilya Dorzdov, Yazdani Lab, Princeton University)

Princeton University scientists used scanning-tunneling microscope to show the atomic structure of an one-atom-wide iron wire on a lead surface. The zoomed-in portion of the image depicts the quantum probability of the wire containing an elusive particle called the Majorana fermion. Importantly, the image pinpoints the particle to the end of the wire, which is where it had been predicted to be over years of theoretical calculations.

(Photo Credit: Yazdani Lab, Princeton University)

Source: Princeton University