Extremely hot temperatures over land have dramatically and unequivocally increased in number and area despite claims that the rise in global average temperatures has slowed over the past 10 to 20 years.

Scientists from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate System Science and international colleagues made the finding when they focused their research on the rise of temperatures at the extreme end of the spectrum where impacts are felt the most.

"It quickly became clear, the so-called "hiatus" in global average temperatures did not stop the rise in the number, intensity and area of extremely hot days" said one of the paper's authors Dr Lisa Alexander.

"Our research has found a steep upward tendency in the temperatures and number of extremely hot days over land and the area they impact, despite the complete absence of a strong El Niño since 1998."

The researchers examined the extreme end of the temperature spectrum because this is where global warming impacts are expected to occur first and are most clearly felt. As Australians saw this summer and the last, extremely hot temperatures in inhabited areas have powerful impacts on our society.

The observations also showed that extremely hot events are now affecting on average more than twice the area when compared to similar events 30 years ago.

To get their results, the researchers examined hot days starting from 1979. Temperatures of every day throughout the year were compared against temperatures on that exact same calendar day from 1979-2012. The hottest 10% of all days over that period were classified as hot temperature extremes.

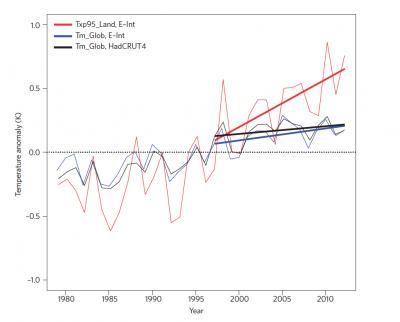

This image shows a time series of temperature anomalies for hot extremes over land (red) and global mean temperature (black, blue). The anomalies are computed with respect to the 1979-2010 time period. The time series are based on the ERA-Interim 95th percentile of the maximum temperature over land (Txp95_Land, red) and the global (ocean + land) mean temperature (Tm_Glob) in ERA-Interim (blue) and HadCRUT4 (black).

(Photo Credit: Nature Climate Change commentary by authors: No pause in the increase of hot temperature extremes)

Globally, on average regions normally expect around 36.5 extremely hot days in a year. The observations showed that during the period from 1997-2012, regions that experienced 10, 30 or 50 extremely hot days above this average saw the greatest upward trends in extreme hot days over time and the area they impacted.

The consistently upward trend persisted right through the "hiatus" period from 1998-2012.

"Our analysis shows there has been no pause in the increase of warmest daily extremes over land and the most extreme of the extreme conditions are showing the largest change," said Dr Markus Donat

"Another interesting aspect of our research was that those regions that normally saw 50 or more excessive hot days in a year saw the greatest increases in land area impact and the frequency of hot days. In short, the hottest extremes got hotter and the events happened more often."

While global annual average near-surface temperatures are a widely used measure of climate change, this latest research reinforces that they do not account for all aspects of the climate system.

A stagnation in the increase of global annual mean temperatures, over a relatively short period of 10 to 20 years, does not imply that global warming has stopped. Other measures, such as extreme temperatures, ocean heat content and the disappearance of land-based ice all show continuous changes that are consistent with a warming world.

"It is important when we take global warming into account, that we use measures that are useful in determining the impacts on our society," said Prof. Sonia Seneviratne from ETH Zurich, who led the study while on sabbatical at the ARC Centre.

"Global average temperatures are a useful measurement for researchers but it is at the extremes where we will most likely find those impacts that directly affect all of our lives. Clearly, we are seeing more heat extremes over land more often as a result of enhanced greenhouse gas warming."

Source: University of New South Wales