Long-necked sauropod dinosaurs include the largest animals ever to walk on land, but they hatched from eggs no bigger than a soccer ball.

A lack of young sauropod fossils, however, has left the earliest lives of these giants shrouded in mystery. Did they require parental care after hatching like some other dinosaurs, or were they self-reliant?

Research funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and led by Kristi Curry Rogers of Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, sheds the first light on the life of a young Rapetosaurus, a titanosaurian sauropod buried in the Upper Cretaceous Maevarano Formation of Madagascar.

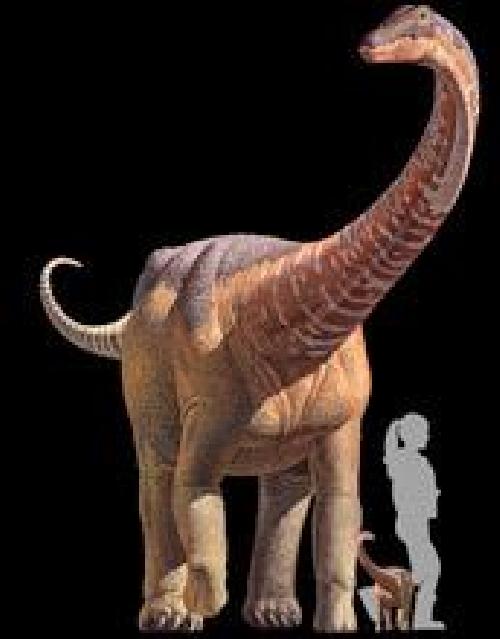

This is a comparison of an adult Rapetosaurus, a baby Rapetosaurus and a human. Credit: Kristi Curry Rogers

This is a comparison of an adult Rapetosaurus, a baby Rapetosaurus and a human. Credit: Kristi Curry Rogers

The findings are published today in the journal Science.

Active at birth

The baby behemoths were active, capable of a wider array of maneuvers than adult members of their species, and didn't need parental care after hatching.

"These scientists employed several lines of evidence to investigate growth strategies in the smallest known post-hatching sauropod dinosaur," said Judy Skog, a program director in NSF's Division of Earth Sciences, which funded the research along with NSF's Division of Environmental Biology.

Skog said the researchers developed tests that could be applied to other perinatal dinosaurs.

"It's intriguing that these animals developed quickly to function on their own, much like some birds and herding mammals of today," she said.

The preserved partial skeleton was so small that its bones were originally mistaken for those of a fossil crocodile, said Curry Rogers.

"This baby's limbs at birth were built for its later adult mass; as an infant, however, it weighed just a fraction of its future size," Curry Rogers said. "This is our first opportunity to explore the life of a sauropod just after hatching, at the earliest stage of its life."

Along with researchers Megan Whitney of the University of Washington, Mike D'Emic of Adelphi University, and Brian Bagley of the University of Minnesota, the team studied thin-sections of the tibia and used a high-powered CT scanner to get a closer look at the microstructures preserved inside the limb bones.

Microscopic bone features

The detailed microscopic features of the Rapetosaurus bones revealed patterns similar to those of living animals and made it possible for the scientists to reconstruct the beginning of the dinosaur's post-hatching life.

"We looked at the preserved patterns of blood supply, growth cartilages at the ends of limb bones, and at bone remodeling," Curry Rogers said. "These features indicate that Rapetosaurus grew as rapidly as a newborn mammal and was only a few weeks old when it died."

The tiny titanosaur was mobile at hatching and less reliant on parental care than other animals. Baby sauropods like Rapetosaurus were somewhat like miniature adults, Curry Rogers said.

The team also observed microscopic zones deep within the bones. They proved similar to the hatching lines in today's reptiles, and to neonatal growth lines in extant mammals.

The zones indicate the time of hatching in Rapetosaurus, and allowed the scientists to estimate the weight of the newly hatched Rapetosaurus -- around 7.7 pounds.

Demise in a drought

What caused the demise of this baby Rapetosaurus?

Clues came from its cartilage growth plates, which bear a striking resemblance to the modified growth cartilages that occur during starvation among living vertebrates.

When taken in the context of the intensely drought-stressed ecosystem represented in the Maevarano Formation, it's clear that this Rapetosaurus had it rough, Curry Rogers said.

"Between its hatching and death just a few weeks later," she said, "this baby Rapetosaurus fended for itself in a harsh and unforgiving environment."

source: National Science Foundation