"Achieving very high packing and alignment of the carbon nanotubes in the fibers is critical," said study co-author Yeshayahu Talmon, director of Technion's Russell Berrie Nanotechnology Institute, who began collaborating with Pasquali about five years ago.

The next big breakthrough came in 2009, when Talmon, Pasquali and colleagues discovered the first true solvent for nanotubes -- chlorosulfonic acid. For the first time, scientists had a way to create highly concentrated solutions of nanotubes, a development that led to improved alignment and packing.

"Until that time, no one thought that spinning out of chlorosulfonic acid was possible because it reacts with water," Pasquali said. "A graduate student in my lab, Natnael Bahabtu, found simple ways to show that CNT fibers could be spun from chlorosulfonic acid solutions. That was critical for this new process."

Pasquali said other labs had found that the strength and conductivity of spun fibers could also be improved if the starting material -- the clumps of raw nanotubes -- contained long nanotubes with few atomic defects. In 2010, Pasquali and Talmon began experimenting with nanotubes from different suppliers and working with AFRL scientists to measure the precise electrical and thermal properties of the improved fibers.

During the same period, Otto was evaluating methods that different research centers had proposed for making CNT fibers. He envisaged combining Pasquali's discoveries, Teijin Aramid's know-how and the use of long CNTs to further the development of high performance CNT fibers. In 2010, Teijin Aramid set up and funded a project with Rice, and the company's fiber-spinning experts have collaborated with Rice scientists throughout the project.

"The Teijin scientific and technical help led to immediate improvements in strength and conductivity," Pasquali said.

Study co-author Junichiro Kono, a Rice professor of electrical and computer engineering, said, "The research showed that the electrical conductivity of the fibers could be tuned and optimized with techniques that were applied after initial production. This led to the highest conductivity ever reported for a macroscopic CNT fiber."

The fibers reported in Science have about 10 times the tensile strength and electrical and thermal conductivity of the best previously reported wet-spun CNT fibers, Pasquali said. The specific electrical conductivity of the new fibers is on par with copper, gold and aluminum wires, but the new material has advantages over metal wires.

For example, one application where high strength and electrical conductivity could prove useful would be in data and low-power applications, Pasquali said.

"Metal wires will break in rollers and other production machinery if they are too thin," he said. "In many cases, people use metal wires that are far more thick than required for the electrical needs, simply because it's not feasible to produce a thinner wire. Data cables are a particularly good example of this."

Scientists have created the first pure carbon nanotube fibers that combine many of the best features of highly conductive metal wires, strong carbon fibers and pliable textile thread. In a Jan. 11 paper in the journal Science, researchers from Rice University, the Dutch firm Teijin Aramid, the US Air Force and Israel's Technion Institute describe an industrially scalable process for making the threadlike fibers, which outperform commercially available products in a number of ways.

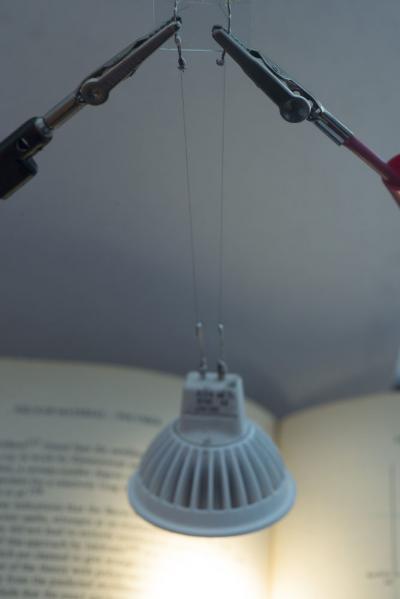

(Photo Credit: Rice University)

This light bulb is powered and held in place by two thin strands of carbon nanotube fibers that look and feel like textile thread. The nanotube fibers conduct heat and electricity as well as metal wires but are stronger and more flexible.

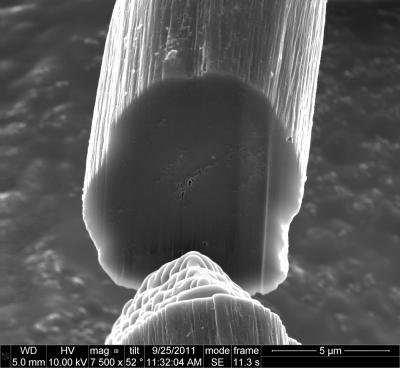

(Photo Credit: Jeff Fitlow/Rice University)

Nanotubes are tightly packed in the new carbon nanotube fibers produced by Rice University and Teijin Aramid. This cross section of a test fiber, which was taken with a scanning electron microscope, shows only a few open gaps inside the fiber.

(Photo Credit: D. Tsentalovich/Rice University)

Source: Rice University