The original SLIPS materials also need to be fastened somehow to existing surfaces, which is often not easy.

"It would be easier to take the existing surface and treat it in a certain way to make it slippery," Vogel explained.

Vogel, Aizenberg, and their colleagues sought to develop a coating that accomplishes this and works as SLIPS does. SLIPS's thin layer of liquid lubricant allows liquids to flow easily over the surface, much as a thin layer of water in an ice rink helps an ice skater glide.

To create a SLIPS-like coating, the researchers corral a collection of tiny spherical particles of polystyrene, the main ingredient of Styrofoam, on a flat glass surface like a collection of Ping-Pong balls. They pour liquid glass on them until the balls are more than half buried in glass. After the glass solidifies, they burn away the beads, leaving a network of craters that resembles a honeycomb. They then coat that honeycomb with the same liquid lubricant used in SLIPS to create a tough but slippery coating.

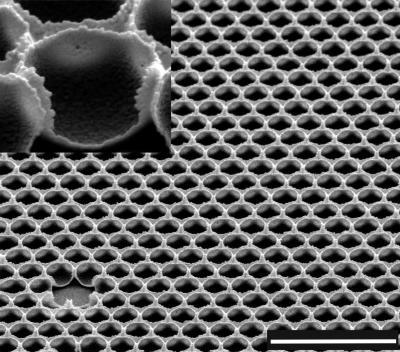

"The honeycomb structure is what confers the mechanical stability to the new coating," said Aizenberg.

By adjusting the width of the honeycomb cells to make them much smaller in diameter than the wavelength of visible light, the researchers kept the coating from reflecting light. This made a glass slide with the coating completely transparent.

These coated glass slides repelled a variety of liquids, just as SLIPS does, including water, octane, wine, olive oil and ketchup. And, like SLIPS, the coating reduced the adhesion of ice to a glass slide by 99 percent. Keeping materials frost-free is important because adhered ice can take down power lines, decrease the energy efficiency of cooling systems, delay airplanes and lead buildings to collapse.

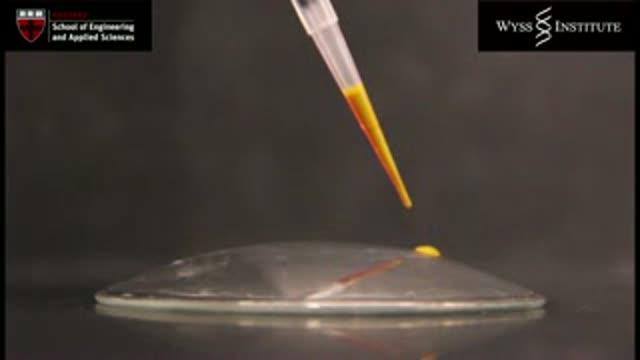

The SLIPS coating makes glass so slippery that droplets of liquids slip off quickly even at a shallow angle. Here, from top to bottom, a droplet of octane, an ingredient of gasoline, rolls off a watch glass in just one second.

(Photo Credit: Nicolas Vogel, Wyss Institute.)

Importantly, the honeycomb structure of the SLIPS coating on the glass slides confers unmatched mechanical robustness. It withstood damage and remained slippery after various treatments that can scratch and compromise ordinary glass surfaces and other popular liquid-repellent materials, including touching, peeling off a piece of tape, wiping with a tissue.

"We set ourselves a challenging goal: to design a versatile coating that's as good as SLIPS but much easier to apply, transparent, and much tougher -- and that is what we managed," Aizenberg said.

The team is now honing its method to better coat curved pieces of glass as well as clear plastics such as Plexiglas, and to adapt the method for the rigors of manufacturing.

"Joanna's new SLIPS coating reveals the power of following Nature's lead in developing new technologies," said Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., the Wyss Institute's Founding Director. "We are excited about the range of applications that could use this innovative coating." Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital, and Professor of Bioengineering at Harvard SEAS.

The tiny, tightly packed cells of the honeycomb-like structure, shown here in this electron micrograph, make the SLIPS coating highly durable.

(Photo Credit: Nicolas Vogel, Wyss Institute)

Researchers create the ultraslippery coating by creating a glass honeycomb-like structure with craters (left), coating it with a Teflon-like chemical (purple) that binds to the honeycomb cells to form a stable liquid film. That film repels droplets of both water and oily liquids (right). Because it's a liquid, it flows, which helps the coating repair itself when damaged.

(Photo Credit: Nicolas Vogel, Wyss Institute.)

Source: Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard