OAK BROOK, Ill. – Babies born 32 to 36 weeks into gestation may have smaller brains and other brain abnormalities that could lead to long-term developmental problems, according to a new study published online in the journal Radiology.

Much of the existing knowledge on preterm birth and brain development has been drawn from studies of individuals born very preterm, or less than 32 weeks into gestation at birth.

For the new study, researchers in Australia focused on moderate and late preterm (MLPT) babies —those born between 32 weeks, zero days, and 36 weeks, six days, into gestation. MLPT babies account for approximately 80 percent of all preterm births and are responsible for much of the rise in the rates of preterm birth over the last 20 years. Despite this, to date there have been no large-scale studies published on brain alterations associated with MLPT birth that may provide insight into brain-behavior relationships in this group of children.

"In those very preterm babies, brain injury from bleeding into the brain or a lack of blood flow, oxygen or nutrition to the brain may explain some of the abnormal brain development that occurs," said the study's lead author, Jennifer M. Walsh, M.B.B.Ch., B.A.O., M.R.C.P.I., from the Royal Women's Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. "However, in some preterm babies, there may be no obvious explanation for why their brain development appears slow compared with babies born on time."

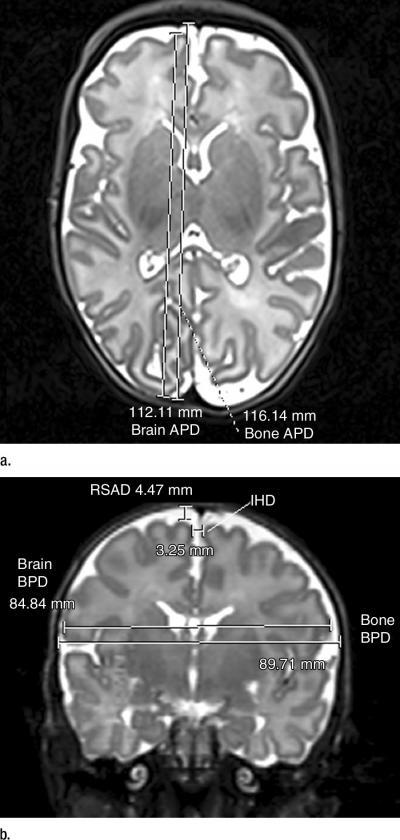

(a) Axial T2-weighted image shows brain and bone antero¬posterior distance (APD). (b) Coronal T2-weighted image shows brain and bone biparietal diameter (BPD), interhemispheric distance (IHD), right superior extra-axial distance (RSAD).

(Photo Credit: Radiological Society of North America)

To learn more, the researchers performed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exams on 199 MLPT and 50 term-born infants (greater than 37 weeks gestation) between 38 to 44 weeks of gestation. They looked for signs of brain injury and compared the size and maturation of multiple brain structures in the two groups.

While injury rates were similar between the two groups, MLPT birth was associated with smaller brain size at term-equivalent age. In addition, MLPT infants had less developed myelination in one part of the brain and more immature gyral folding compared with term-born controls. Myelination—the formation of a fatty insulating sheath around some nerve fibers—and gyral folding—the folding of the cerebral cortex to increase the brain's surface area—are important processes in early brain development.

The findings suggest that MLPT birth may disrupt the expected trajectory of brain growth that would normally occur in the last two or so months in utero, according to Dr. Walsh.

"Given that brain growth is very rapid in the last one-third of pregnancy, it is perhaps not surprising that being born during this potentially vulnerable period may disrupt brain development," she said. "Brain growth is very complex, involving not only the neurons with which we think and do things, but also the other brain cells that support the neurons and are vital for normal brain function."

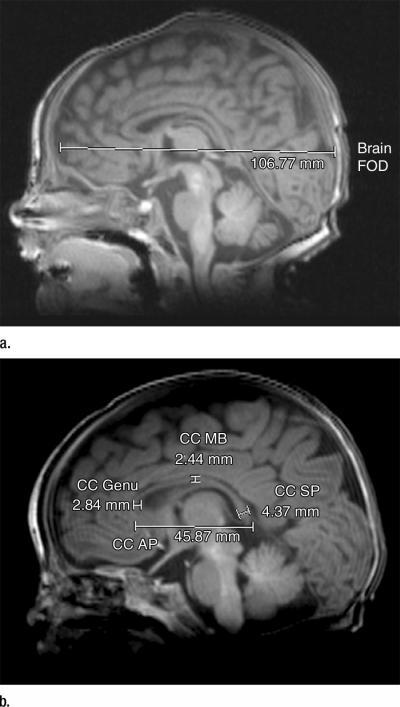

(a) Sagittal T1-weighted image shows brain fronto-occipital distance (FOD). (b) corpus callosum (CC), anteroposterior distance (AP), genu, midbody (MB), splenium (SP) measurements.

(Photo Credit: Radiological Society of North America)

The researchers are hoping to learn in greater depth the impact that moderate to late preterm birth has on the brain, so that they can then begin to try different treatments designed to improve brain function and long-term outcome in these infants.

"Medications, along with early intervention to help parents understand their baby's needs, have been effective in helping very preterm babies catch up to their term-born peers," Dr. Walsh said. "However, whether any of the existing treatments will help babies born between 32 and 36 weeks is unknown, as they have not been studied very much at all."

The researchers plan to follow the infants in the study group through childhood to learn more about the relationship between brain abnormalities and later outcomes. They also are assessing additional MRI information about brain structure and function in these children.

"Understanding what problems they have and what might be causing them is the first step in trying to improve their long-term outcome," Dr. Walsh said.

(a) Axial T2-weighted image shows deep gray nuclei (DGN) width, anteroposterior (AP) distance, and surface area. (b) Coronal T2- weighted image shows lateral ventricle atrial measures and transverse cerebellar diameter (TCD).

(Photo Credit: Radiological Society of North America)