A survey of 10 hot, Jupiter-sized exoplanets conducted with NASA's Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes has led a team to solve a long-standing mystery -- why some of these worlds seem to have less water than expected. The findings offer new insights into the wide range of planetary atmospheres in our galaxy and how planets are assembled.

Of the nearly 2,000 planets confirmed to be orbiting other stars, a subset are gaseous planets with characteristics similar to those of Jupiter but orbit very close to their stars, making them blistering hot.

Their close proximity to the star makes them difficult to observe in the glare of starlight. Due to this difficulty, Hubble has only explored a handful of hot Jupiters in the past. These initial studies have found several planets to hold less water than predicted by atmospheric models.

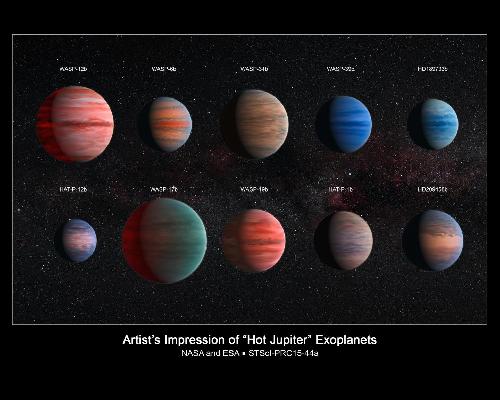

This image shows an artist's impression of the ten hot Jupiter exoplanets studied by astronomer David Sing and his colleagues using the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes. From top left to lower left, these planets are WASP-12b, WASP-6b, WASP-31b, WASP-39b, HD 189733b, HAT-P-12b, WASP-17b, WASP-19b, HAT-P-1b and HD 209458b. Credit: NASA, ESA, and D. Sing (University of Exeter)

This image shows an artist's impression of the ten hot Jupiter exoplanets studied by astronomer David Sing and his colleagues using the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes. From top left to lower left, these planets are WASP-12b, WASP-6b, WASP-31b, WASP-39b, HD 189733b, HAT-P-12b, WASP-17b, WASP-19b, HAT-P-1b and HD 209458b. Credit: NASA, ESA, and D. Sing (University of Exeter)

The international team of astronomers has tackled the problem by making the largest-ever spectroscopic catalogue of exoplanet atmospheres. All of the planets in the catalog follow orbits oriented so the planet passes in front of their parent star, as seen from Earth. During this so-called transit, some of the starlight travels through the planet's outer atmosphere. "The atmosphere leaves its unique fingerprint on the starlight, which we can study when the light reaches us," explains co-author Hannah Wakeford, now at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

By combining data from NASA's Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes, the team was able to attain a broad spectrum of light covering wavelengths from the optical to infrared. The difference in planetary radius as measured between visible and infrared wavelengths was used to indicate the type of planetary atmosphere being observed for each planet in the sample, whether hazy or clear. A cloudy planet will appear larger in visible light than at infrared wavelengths, which penetrate deeper into the atmosphere. It was this comparison that allowed the team to find a correlation between hazy or cloudy atmospheres and faint water detection.

"I'm really excited to finally see the data from this wide group of planets together, as this is the first time we've had sufficient wavelength coverage to compare multiple features from one planet to another," says David Sing of the University of Exeter, U.K., lead author of the paper. "We found the planetary atmospheres to be much more diverse than we expected."

"Our results suggest it's simply clouds hiding the water from prying eyes, and therefore rule out dry hot Jupiters," explained co-author Jonathan Fortney of the University of California, Santa Cruz. "The alternative theory to this is that planets form in an environment deprived of water, but this would require us to completely rethink our current theories of how planets are born."

The results are being published in the Dec. 14 issue of the British science journal Nature.

The study of exoplanetary atmospheres is currently in its infancy. Hubble's successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, will open a new infrared window on the study of exoplanets and their atmospheres.

source: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center