Biomedical engineering researchers at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have developed a technique that uses a patch embedded with microneedles to deliver cancer immunotherapy treatment directly to the site of melanoma skin cancer. In animal studies, the technique more effectively targeted melanoma than other immunotherapy treatments.

According to the CDC, more than 67,000 people in the United States were diagnosed with melanoma in 2012 alone - the most recent year for which data are available. If caught early, melanoma patients have a 5-year survival rate of more than 98 percent, according to the National Cancer Institute. That number dips to 16.6 percent if the cancer has metastasized before diagnosis and treatment. Melanoma treatments range from surgery to chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A promising new field of cancer treatment is cancer immunotherapy, which helps the body's own immune system fight off cancer.

In the immune system, T cells are supposed to identify and kill cancer cells. To do their job, T cells use specialized receptors to differentiate healthy cells from cancer cells. But cancer cells can trick T cells. One way cancer cells do this is by expressing a protein ligand that binds to a receptor on the T cells to prevent the T cell from recognizing and attacking the cancer cell.

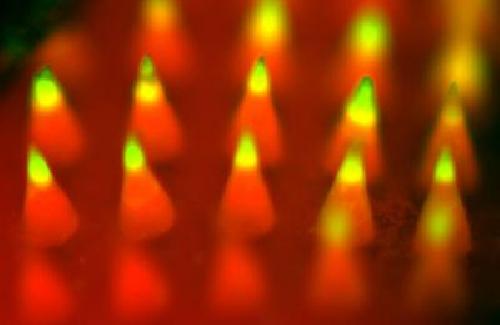

Fluorescence imaging of a microneedle patch. Biomedical researchers have developed a technique that uses a patch embedded with microneedles -- like the patch pictured here -- to deliver cancer immunotherapy treatment directly to the site of melanoma skin cancer. In animal studies, the technique more effectively targeted melanoma than other immunotherapy treatments. Credit: Yanqi Ye

Fluorescence imaging of a microneedle patch. Biomedical researchers have developed a technique that uses a patch embedded with microneedles -- like the patch pictured here -- to deliver cancer immunotherapy treatment directly to the site of melanoma skin cancer. In animal studies, the technique more effectively targeted melanoma than other immunotherapy treatments. Credit: Yanqi Ye

Recently, cancer immunotherapy research has focused on using "anti-PD-1" (or programmed cell death) antibodies to prevent cancer cells from tricking T cells.

"However, this poses several challenges," says Chao Wang, co-lead author of a paper on the microneedle research and a postdoctoral researcher in the joint biomedical engineering program at NC State and UNC-Chapel Hill. "First, the anti-PD-1 antibodies are usually injected into the bloodstream, so they cannot target the tumor site effectively. Second, the overdose of antibodies can cause side effects such as an autoimmune disorder."

To address these challenges, the researchers developed a patch that uses microneedles to deliver anti-PD-1 antibodies locally to the skin tumor. The microneedles are made from hyaluronic acid, a biocompatible material.

The anti-PD-1 antibodies are embedded in nanoparticles, along with glucose oxidase - an enzyme that produces acid when it comes into contact with glucose. These nanoparticles are then loaded into microneedles, which are arrayed on the surface of a patch.

When the patch is applied to a melanoma, blood enters the microneedles. The glucose in the blood makes the glucose oxidase produce acid, which slowly breaks down the nanoparticles. As the nanoparticles degrade, the anti-PD-1 antibodies are released into the tumor.

"This technique creates a steady, sustained release of antibodies directly into the tumor site; it is an efficient approach with enhanced retention of anti-PD-1 antibodies in the tumor microenvironment," says Zhen Gu, an assistant professor in the biomedical engineering program and senior author of the paper.

The researchers tested the technique against melanoma in a mouse model. The microneedle patch loaded with anti-PD-1 nanoparticles was compared to treatment by injecting anti-PD-1 antibodies directly into the bloodstream and to injecting anti-PD-1 nanoparticles directly into the tumor.

"After 40 days, 40 percent of the mice who were treated using the microneedle patch survived and had no detectable remaining melanoma - compared to a zero percent survival rate for the control groups," says Yanqi Ye, a Ph.D. student in Gu's lab and co-lead author of the paper.

The researchers also created a drug cocktail, consisting of anti-PD-1 antibodies and another antibody called anti-CTLA-4 - which also helps T cells attack the cancer cells.

"Using a combination of anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 in the microneedle patch, 70 percent of the mice survived and had no detectable melanoma after 40 days," Wang says.

"Because of the sustained and localized release manner, mediated by microneedles, we are able to achieve desirable therapeutic effects with a relatively low dosage, which reduces the risk of auto-immune disorders," Gu says.

"We're excited about this technique, and are seeking funding to pursue further studies and potential clinical translation," Gu adds.

source: North Carolina State University