Like symbiotic species, a galaxy and its central black hole lead intimately connected lives. The details of this relationship still pose many puzzles for astronomers.

Some black holes actively accrete matter. Part of this material do not fall into the black hole but is ejected in a narrow stream of particles, traveling at nearly the speed of light. When the stream slows down, it creates a tenuous bubble that can engulf the entire galaxy. Invisible to optical telescopes, the bubble is very prominent at low radio frequencies. The new International LOFAR Telescope - designed and built by ASTRON in an international collaboration - is ideally suited to detect this low frequency emission.

Astronomers have produced one of the best images ever of such a bubble, using LOFAR to detect frequencies from 20 to 160 MHz. "The result is of great importance", says Francesco de Gasperin, lead author of the study that is being published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. "It shows the enormous potential of LOFAR, and provides compelling evidence of the close ties between black hole, host galaxy, and their surroundings."

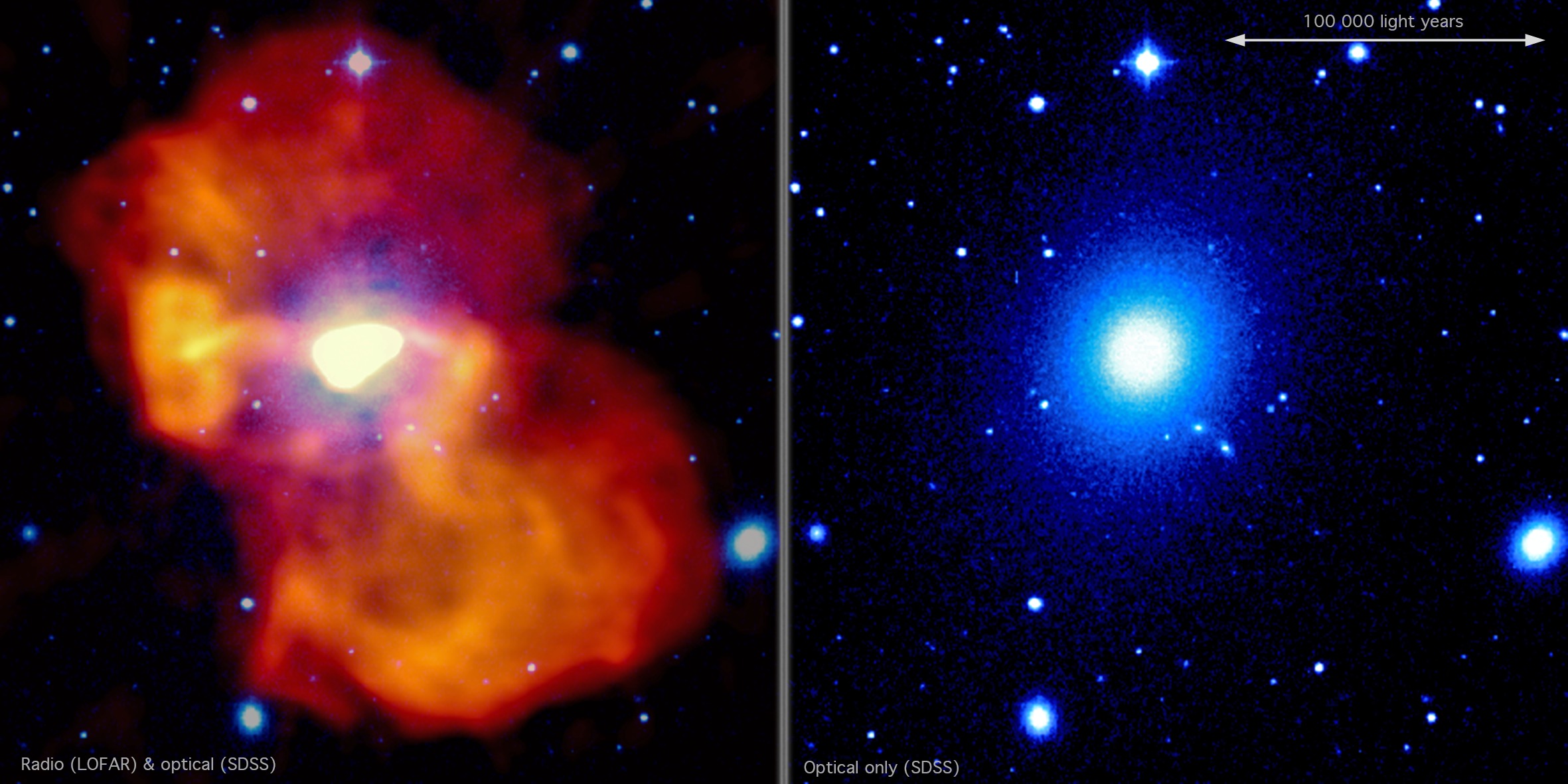

This false colour image shows the galaxy M87. Optical light is shown in white/blue (SDSS), the radio emission in yellow/orange (LOFAR). At the centre, the radio emission has a very high surface brightness, showing where the jet powered by the supermassive black hole is located. Credits: Francesco de Gasperin, on behalf of the LOFAR collaboration

The image was made during the test-phase of LOFAR, and targeted the giant elliptical galaxy Messier 87, at the centre of a galaxy cluster in the constellation of Virgo. This galaxy is 2000 times more massive than our Milky Way and hosts in its centre one of the most massive black holes discovered so far, with a mass six billion times that of our Sun. Every few minutes this black hole swallows an amount of matter similar to that of the whole Earth, converting part of it into radiation and a larger part into powerful jets of ultra-fast particles, which are responsible for the observed radio emission.

“This is the first time such high-quality images are possible at these low frequencies", says professor Heino Falcke, chairman of the board of the ILT and co-author of the study. "This was a challenging observation - we did not expect to get such fantastic results so early in the commissioning phase of LOFAR."

To determine the age of the bubble, the authors added radio observations at different frequencies from the Very Large Array in New Mexico (USA), and the Effelsberg 100-meter radio telescope near Bonn (Germany). The team found that this bubble is surprisingly young, just about 40 million years, which is a mere instant on cosmic time scales. The low frequency observation does not reveal any relic emission outside the well-confined bubble boundaries, this means that the bubble is not just a relic of an activity that happened long ago but is constantly refilled with fresh particles ejected by the central black hole.

"What is particularly fascinating", says Andrea Merloni from the Max-Planck Institute of Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, who supervised de Gasperin's doctoral work, "is that the results also provide clues on the violent matter-to-energy conversion that occurs very close to the black hole. In this case the black hole is particularly efficient in accelerating the jet, and much less effective in producing visible emission."

Francesco de Gasperin performed the study as part of his PhD work at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics and at the Excellence Cluster Universe. De Gasperin is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Hamburg.