New York, NY, January 6, 2015--Scientists at Columbia University's Mortimer B. Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC), and the Université Paris Descartes have found that deficits in social memory--a crucial yet poorly understood feature of psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia--may be due to a decrease in the number of a particular class of brain cells, called inhibitory neurons, in a little-explored region within the brain's memory center.

The findings, which were reported today in the journal Neuron, explain some of the underlying mechanisms that lead to the more difficult-to-treat symptoms of schizophrenia, including social withdrawal, reduced motivation and decreased emotional capacity.

Scientists have long speculated that schizophrenia, which affects about 1 in every 100 adults worldwide, originates in part in the hippocampus--the brain's headquarters for memory and spatial navigation. As a result, nearly every region of the hippocampus has been studied extensively in the hopes of gaining insight into the disorder. One notable exception is a tiny region of the hippocampus known as CA2.

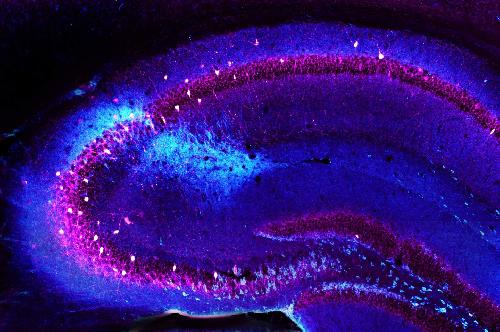

This is an image of the mouse hippocampus, with CA2 inhibitory neurons stained in light blue. In the researchers' mouse model of schizophrenia, this region showed significant depletion of neurons and was accompanied by a deficit in social memory. Credit: Vivien Chevaleyre

This is an image of the mouse hippocampus, with CA2 inhibitory neurons stained in light blue. In the researchers' mouse model of schizophrenia, this region showed significant depletion of neurons and was accompanied by a deficit in social memory. Credit: Vivien Chevaleyre

"Smaller and less well-defined than other parts of the hippocampus, CA2 was like a small island that was depicted on old maps but remained unexplored," explained Vivien Chevaleyre, PhD, group leader in neuroscience at the Université Paris Descartes and a lead author of the paper.

Several discoveries have focused attention on a possible association between CA2 and schizophrenia. This region of the hippocampus is associated with vasopressin, a hormone that plays a role in sexual bonding, motivation and other intensely social behaviors, which become impaired in people with the disorder. In addition, postmortem examinations of people with schizophrenia have revealed a marked decrease in the number of CA2 inhibitory neurons, while the rest of the hippocampus remained largely unaffected. However, the significance of this loss had remained unclear.

In this study, the researchers performed a series of electrophysiological and behavioral experiments on a mouse model of schizophrenia developed at CUMC.

By examining the brains of these mice, the researchers observed a substantial decrease in inhibitory CA2 neurons, as compared to a control group of normal, healthy mice--a change remarkably similar to that previously observed in postmortem examinations of people with schizophrenia. Moreover, the team discovered that the modified mice had a significantly reduced capacity for social memory compared with the controls. This raises the hypothesis that changes to CA2 may account for some of the social behavioral changes that occur in individuals with the disorder.

"Even the timing of the emergence of symptoms in the mice--during young adulthood--parallels the onset of schizophrenia in humans," said Joseph Gogos, PhD, a professor of physiology and neuroscience at CUMC, a principal investigator at the Zuckerman Institute and a lead author of the paper.

"We can now examine the effects of schizophrenia at the cellular level and at the behavioral level," said Steven Siegelbaum, PhD, chair of the Department of Neuroscience at CUMC, a principal investigator at the Zuckerman Institute and a co-author of the paper. "This essentially opens up a whole new avenue for research that could lead to earlier diagnosis and more effective treatments for schizophrenia."

source: Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute