Researchers from the Institut Pasteur, Inserm, CNRS and Paris Descartes - Sorbonne Paris Cité University recently published a large-scale study in Nature Genetics based on almost 7,000 strains of Listeria monocytogenes -- the bacterium responsible for human listeriosis, a severe foodborne infection. Through the integrative analysis of epidemiological, clinical and microbiological data, the researchers have revealed the highly diverse pathogenicity of isolates belonging to this bacterial species. Comparative genomics led them to discover new virulence factors, which were demonstrated experimentally as involved in cerebral and fetal-placental listeriosis. In addition, this research points to the importance of using new reference strains, which are representative of the hypervirulent lineages identified here, for experimental research on Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis.

In France, as in many other countries, the Listeria monocytogenes bacterium -- which is responsible for listeriosis, a severe foodborne infection, especially in pregnant women and the elderly -- is subjected to a stringent microbiological monitoring system, coordinated at the Institut Pasteur by the National Reference Center (CNR) for Listeria together with the French Institute for Public Health Surveillance (InVS). Researchers from the Biology of Infection Unit (Institut Pasteur/Inserm), headed by Marc Lecuit (Paris Descartes - Sorbonne Paris Cité University, Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital, AP-HP) and home to the Listeria CNR, together with the group led by Sylvain Brisse in the Microbial Evolutionary Genomics Unit (Institut Pasteur/CNRS), recently published the findings of a broad study of close to 7,000 strains of Listeria monocytogenes isolates collected over the past nine years for monitoring purposes.

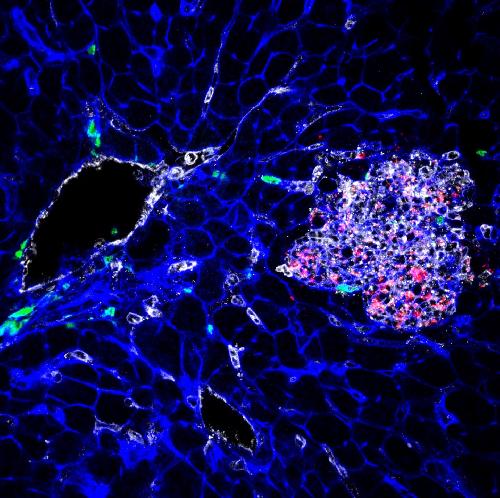

This image shows tissue infected by Listeria (bacteria appear in red). Credit: YH Tsai, M Lecuit, © Institut Pasteur.

This image shows tissue infected by Listeria (bacteria appear in red). Credit: YH Tsai, M Lecuit, © Institut Pasteur.

First and foremost, bacterial molecular genotyping revealed considerable heterogeneity within the L. monocytogenes species, and showed that strains can be categorized into distinct genetic families (or clonal groups). By analyzing epidemiological data, the researchers showed that some of these clonal groups are more frequently associated with human infections, while others are closely linked to food. The comprehensive analysis of detailed clinical data from over 800 patients with listeriosis showed that the strains most often associated with infections are more frequently isolated in the least immunodeficient patients while the strains most commonly linked to food mainly infect the most immunodeficient individuals. In addition, the strains most often involved in infections appear to be the most invasive as they infect the central nervous system and fetus more often than the strains most commonly associated with food. These findings suggested the existence of hypervirulent strains -- an hypothesis that scientists confirmed thanks to a humanized mouse model of listeriosis they developed previously .

To uncover the genetic basis of this hypervirulence, the researchers sequenced the genomes of around a hundred strains that are representative of the most prevalent clonal groups. Comparative analysis of these genome sequences identified a large number of genes closely linked to the hypervirulent clonal groups, including one which was demonstrated as involved in the cerebral and fetal-placental tropism of L. monocytogenes experimentally. These results pave the way to a detailed understanding of the mechanisms underlying L. monocytogenes central nervous system and fetal-placental invasion.

While current research on L. monocytogenes is conducted with so called "reference" strains, which are not hypervirulent, this research supports the use of hypervirulent strains representative of human infections, to ensure the clinical and pathophysiological relevance of experimental research.

This study illustrates the exceptional power of harnessing the biodiversity of a given microbial species (here L. monocytogenes) and integrating epidemiological, clinical, bacteriological and experimental data to study the biology of infection in a clinically relevant manner.

source: Institut Pasteur