The study, which was led by graduate students Gavin Woodruff from UMD and Janice Ting from the University of Toronto, was published on July 29, 2014 in the journal PLOS Biology. Woodruff is now a postdoctoral researcher at the Forestry and Forest Research Products Institute in Japan.

The researchers believe the "killer sperm" may be the result of a divergence in the evolution of worm species' sexual organs—in particular, the ability of sperm to physically compete with one another. When a female worm mates with multiple males, the sperm jostle each other, competing for access to the eggs. Female worms' bodies must be able to withstand this competition to survive and produce offspring. The researchers hypothesize that the aggressiveness of the sperm and the ability of the uterus to tolerate the sperm are the same within a single species, but not across multiple species. Thus, a female from a species with less active sperm may not be able to tolerate the aggressive sperm from a different species.

There is evidence for this theory. In the current study, three species of hermaphrodite worms—which produce their own sperm and fertilize their own eggs to reproduce—were especially susceptible to sterility and death when mated with males of other species. The hermaphrodite uterus may have evolved to tolerate "gentler" sperm, but not the larger, more active sperm of non-hermaphrodite species, according to the researchers.

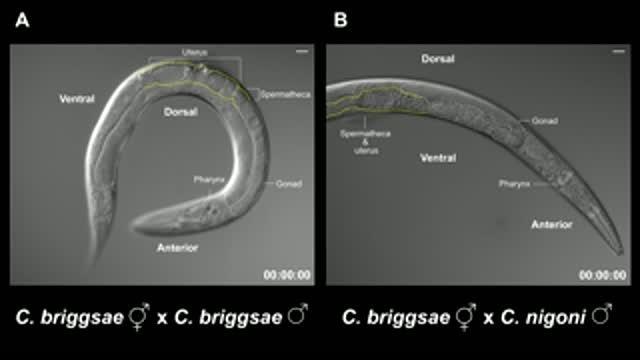

These are time-lapse videos of Caenorhabditis hermaphrodites that were (A) mated with the same species and (B) mated with a different species. Male sperm were fluorescently labeled and appear as white dots. In A, sperm localize normally to the spermatheca and uterus (outlined in yellow) and in B, sperm migrate abnormally outside of the gonad (outlined in white). Scale bar represents 100 microns. Images were taken every 10 seconds and the video is sped up 10X.

(Photo Credit: Janice Ting)

"We found that hermaphrodites can sense, and try to avoid, males of species that can harm them," added Haag.

This instance of lethal cross-species mating is of special interest to evolutionary biologists, Haag notes, because it's unclear how the many species on earth -- 8.7 million, not counting bacteria, according to an estimate published in Nature—remain distinct from each other.

"Punishing cross-species mating by sterility or death would be a powerful evolutionary way to maintain a species barrier," Haag said.

However, evolution usually leaves a few survivors behind, even in the most adverse conditions. The researchers had previously found that the harmful crosses between species nevertheless can produce a few viable offspring. Haag plans to follow up on this study by investigating how these hybrid worms behave when they are bred to different species.

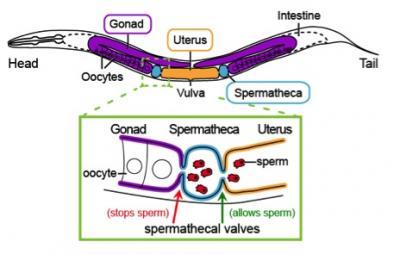

This is an illustration showing the anatomy of a Caenorhabditis female/hermaphrodite worm. Sperm crawl from the uterus to the site of fertilization (spermatheca). The spermathecal valve prevents sperm from crawling into the gonad, but allows eggs (oocytes) to move into the spermatheca to be fertilized.

(Photo Credit: Janice Ting)

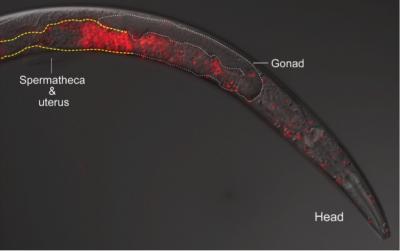

This image depicts an instance of cross-species breeding gone awry. Fluorescence microscopy reveals sperm, in red, invading a female worm's body.

(Photo Credit: Gavin Woodruff)

Source: University of Maryland