The system, known as Kepler-47, harbours the smallest known transiting circumbinary planets -- planets orbiting a pair of stars -- to date. The planets were discovered using NASA's Kepler space telescope [1] by monitoring thefaint drop in brightness produced when both planets transit (eclipse) their host stars [2].

"In contrast to a single planet orbiting a single star, planets whirling around a binary system transit a moving target," explains Jerome Orosz (San Diego State University, USA), lead author of the study. "The time intervals between the transits and their duration can vary substantially, from days to hours, and therefore the extremely precise and almost continuous observations with Kepler space telescope were fundamental."

This planetary system is located roughly 5000 light-years away from Earth, in the constellation of Cygnus (The Swan). The pair of stars whirls around each other every 7.5 days. One star is similar to our Sun while the other is a diminutive star only one third the size and 175 times fainter.

Thanks to Kepler's observations, astronomers were able to characterise the planetary system. The inner planet -- Kepler-47b -- is only three times larger in diameter than the Earth and orbits the stellar pair every 49 days. The outer planet -- Kepler-47c -- is about 4.5 times the size of the Earth -- slightly larger than Uranus -- and orbits the stars every 303 days. This makes the outer planet the longest-period transiting planet currently known.

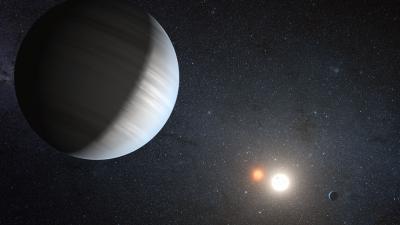

This is an artist's impression of the Kepler-47 system.

(Photo Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/T.Pyle)

More importantly, the outer planet's orbit places the planet well within what astronomers refer to as the habitable zone -- the region around a star within a terrestrial planet that could have liquid water on its surface.

"While the outer planet is probably a gas giant planet and thus not suitable for life, large moons, if present, would be interesting worlds to investigate as they could potentially harbour life," says William Welsh (San DiegoState University, USA), co-author of the study.

Since both planets are rather small, they do not gravitationally disturb the stars or each other measurably. Hence their masses cannot be directly measured. However, astronomers can place upper limits to their masses, showingthat these small objects are certainly planets and not brown dwarfs [3]. Based on their size, the inner and outer planets probably have masses of approximately 8 and 20 times that of the Earth, respectively.

"Since about one third of all stars are either binary or multiple star systems, finding planets in binary star systems has very important implicationsnot only for estimating the total numbers of planets that exist, but for how star-planet systems form as well," concludes Jerome Orosz.

Source: International Astronomical Union