PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- In a Harrisburg, Pa., Federal courtroom 11 years ago, Brown University biologist Kenneth Miller was the first witness in a historic takedown of Intelligent Design's pretense of scientific relevance. In the context of ongoing culture wars over evolution, climate change, stem cell research and vaccination, Miller will reunite with figures from the Kitzmiller v. Dover trial to review that trial's lessons at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Washington, D.C., Feb. 13, 2016.

"Effective public advocacy on the part of science is as necessary today, maybe more necessary, than it was in this trial," said Miller, professor in molecular biology, cell biology and biochemistry.

The case was the first legal challenge to teaching Intelligent Design (ID) in science classes as an alternative to evolution. Miller testified about why ID was not science and, moreover, how it failed to offer a valid critique of evolution. The rest of the plaintiffs' case built on Miller's testimony ultimately to show that the Dover school board inserted ID into the science curriculum specifically to infuse a specific religious doctrine into high school science classes.

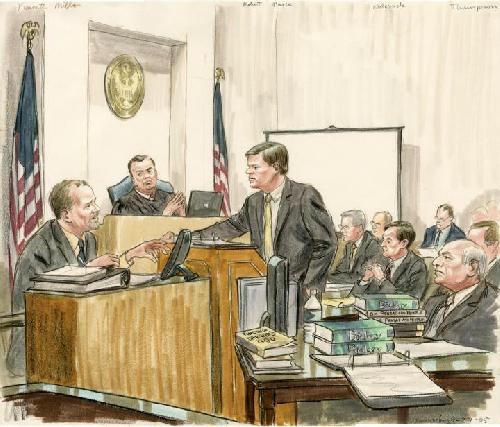

Brown University biologist Kenneth Miller testifies with attorney Witold Walczak in Kitzmiller v. Dover, a 2005 case that prevented Intelligent Design from being taught in science classes. Credit: Art Lien/courtartist.com

Brown University biologist Kenneth Miller testifies with attorney Witold Walczak in Kitzmiller v. Dover, a 2005 case that prevented Intelligent Design from being taught in science classes. Credit: Art Lien/courtartist.com

Miller was one member of a diverse team of scientists, philosophers, teachers, and even a theologian who defended evolution on behalf of 11 Dover-area high school parents who had brought a First Amendment lawsuit against the Dover Board of Education. Miller can hardly be accused of simply opposing religion. A practicing Catholic and author of Finding Darwin's God, he has long argued, including at the AAAS meeting in Vancouver in 2011, that science and faith are compatible.

But they are distinct, he said. That's why the attempt by creationists to masquerade ID as science was unacceptable. Both in the intellectually diverse and persuasive team it assembled and in the way it presented its logic and evidence, Miller said, the Kitzmiller side provided a playbook for standing up for science in contentious public debates.

Spotting a fake ID

Job one in Harrisburg was to convince Judge John Jones III, who will speak alongside Miller at AAAS, that ID was not flawed science, but instead not even science at all.

"There is no First Amendment protection against bad science," Miller said. "If you think incorrect science is being taught in the schools you don't have a constitutional argument against it. But if you think that what is being taught in the schools is a deliberate subterfuge to advance religion, you do have a constitutional case."

Miller said he told the court that ID was really about creation. After all, organisms and their constituent parts do exist. Therefore, Miller said, the claim that they were "designed" really is creationism by another name.

"Any act of design that we can detect also involves an act of creation," Miller said. "When they say for example the proteins that clot our blood, which are very complicated, were 'designed,' that's not sufficient because they are actually claiming that those proteins, or the DNA sequences that code for them, were specially created."

Meanwhile, he said, science is concerned with testing falsifiable hypotheses about natural processes. ID's requirement of "intelligence" for the spontaneous creation of biological entities, however, is untestable and, by ID proponents' own claims, supernatural. That doesn't necessarily make it wrong, Miller noted, it just makes it something other than science.

"If it did exist, science would not be competent to investigate it," Miller said. "Intelligent Design could be correct, but it wouldn't be scientific because it's untestable."

After testifying that ID material was inherently out of place in a science classroom, Miller and American Civil Liberties Union attorney Witold Walczak moved on to debunk ID's central tenets. Showing that ID was merely an unfounded attack on evolution allowed subsequent witnesses to question the real purpose the school board had for insinuating it into the curriculum.

"The so-called arguments in favor of intelligent design were actually not arguments in favor of intelligent design, rather they were arguments against evolution," Miller said.

The crux of the ID claim was that some biological features could not have evolved piece-by-piece because they were "irreducibly complex." Only if they happened all at once could they provide any benefit to an organism. One of the key examples was the tail-like flagellum that propels some bacteria through fluids. With about 40 constituent proteins, a flagellum would seem too complex to have ever evolved through so many seemingly purposeless stages before finally becoming useful.

But as Miller testified, scientists had in fact observed that in organisms missing as many as 30 of those proteins, the 10 remaining ones composed a structure with an entirely different purpose -- it acts like a syringe that bacteria possessing it use to puncture and feast on other cells.

"What that shows is the premise, the core, of intelligent design -- take away even one part and it's no longer functional -- is wrong," Miller said.

Lessons for other debates

In the end, Judge Jones ruled that ID was "creationism relabeled.". But ideological or religiously motivated attempts to influence science education, ID design, persist. As many as 10 states have rejected the National Academy of Sciences' Next Generation Science Standards because they include evolution, climate change, and embryonic stem cells, Miller said.

As in the Dover trial, scientists should not try to fight these battles alone, Miller said. Smart legal strategists and an intellectually broad set of witnesses combined to make the case succeed, he said. Their arguments, in turn, could not have even begun without the welcome and support of parents, teachers, and others in Dover.

"The Kitzmiller v. Dover case is a spectacular example of the way in which ordinary people, parents, school board members, and people in the community can come together and form a uniform alliance in favor of quality science education," Miller said.

He has little doubt such coalitions will need to form again.

source: Brown University