Using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, astronomers at the University of Arizona have taken the first direct, time-resolved images of an exoplanet. Their results were published today in The Astrophysical Journal.

The young, gaseous exoplanet known as 2M1207b, located some 160 light-years from Earth, is four times the mass of Jupiter and orbits a failed star, known to astronomers as a brown dwarf. And while our solar system is 4.5 billion years in the making, 2M1207b is a mere ten million years old. Its days are short--less than 11 hours--and its temperature is hot--a blistering 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit. Its rain showers come in the form of liquid iron and glass.

The researchers, led by UA Department of Astronomy graduate student Yifan Zhou, were able to deduce the exoplanet's rotational period and better understand its atmospheric properties--including its patchy clouds--by taking 160 images of the target over the course of ten hours. Their work was made possible by the high resolution and high contrast imaging capabilities of Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3.

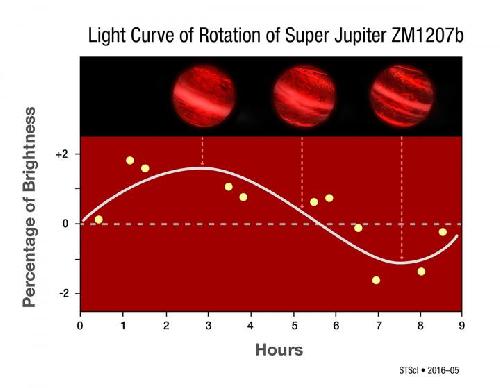

This graph shows changes in the infrared brightness of 2M1207b as measured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Over the course of the 10-hour observation, the planet showed a change in brightness, suggesting the presence of patchy clouds that influence the amount of infrared radiation observed as the planet rotates. Credit: NASA, ESA, Y. Zhou (University of Arizona), and P. Jeffries (STScI)

This graph shows changes in the infrared brightness of 2M1207b as measured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Over the course of the 10-hour observation, the planet showed a change in brightness, suggesting the presence of patchy clouds that influence the amount of infrared radiation observed as the planet rotates. Credit: NASA, ESA, Y. Zhou (University of Arizona), and P. Jeffries (STScI)

"Understanding the exoplanet's atmosphere was one of the key goals for us. This can help us understand how its clouds form and if they are homogenous or heterogeneous across the planet," said Zhou.

Before now, nobody had ever used 26-year-old Hubble to create time-resolved images of an exoplanet.

Even the largest telescope on Earth could not snap a sharp photo of a planet as far away as 2M1207b, so the astronomers created an innovative, new way to map its clouds without actually seeing them in sharp relief: They measured its changing brightness over time.

Daniel Apai, UA assistant professor of astronomy and planetary sciences, is the lead investigator of this Hubble program. He said, "The result is very exciting. It gives us a new technique to explore the atmospheres of exoplanets."

According to Apai, this new imaging technique provides a "method to map exoplanets" and is "an important step for understanding and placing our planets in context." Our Solar System has a relatively limited sampling of planets, and there is no planet as hot or as massive as 2M1207b within it.

Steward Observatory Astronomer Glenn Schneider and Lunar and Planetary Laboratory Professor Adam Showman coauthored the study.

"2M1207b is likely just the first of many exoplanets we will now be able to characterize and map," said Schneider.

"Do these exotic worlds have banded cloud patterns like Jupiter? How is the weather and climate on these extremely hot worlds similar to or different from that of the colder planets in our own solar system? Observations like these are key to answering these questions," said Showman.

Zhou and his collaborators began collecting data for this project in 2014. It began as a pilot study to demonstrate that space telescopes like Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope, which NASA will launch in late 2018, can be used to map clouds on other planets.

The success of this study lead to a new, larger program: Hubble's Cloud Atlas program for which Apai is also the lead investigator. As one of Hubble's largest exoplanet-focused programs, Cloud Atlas represents a collaboration between 14 experts from across the globe, who are now creating more time-resolved images of other planets using the space telescope.

source: University of Arizona