WHAT:Two medical imaging techniques, called positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT), could be used in combination as a biomarker to predict the effectiveness of antibiotic drug regimens being tested to treat tuberculosis (TB) patients, according to researchers at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health. With multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB) on the rise worldwide, new biomarkers are needed to determine whether a particular TB drug regimen is effective.

Traditionally used to detect cancer, PET imaging shows how organs and tissues are functioning. When used with X-rays generated from CT scans, PET scans provide a more complete picture of the area of the body being examined. In two separate studies, NIAID scientists and collaborators demonstrated the utility of PET/CT imaging in monitoring antibiotic treatment effects in both TB-infected monkeys and humans. In the first study, researchers monitored macaques treated with two antibiotics by observing changes on PET/CT scans as well as determining the amount of bacteria remaining after treatment in the animals' lungs, the standard method for assessing TB therapy effectiveness. The researchers applied the same approaches to TB-infected people taking one of the antibiotics and found that changes in human PET/CT scans over the course of treatment were comparable to those seen in monkeys.

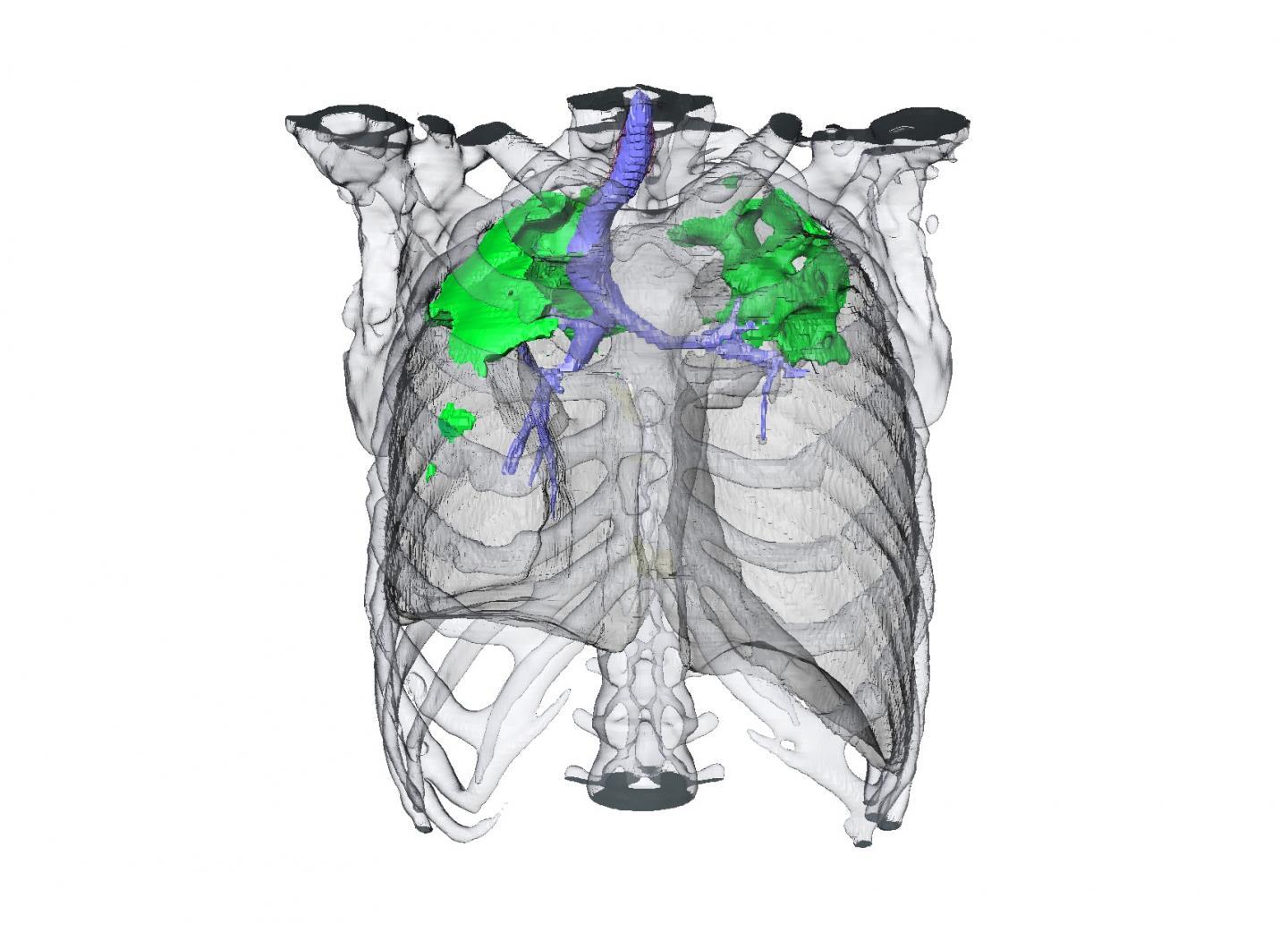

This is a CT scan showing a TB patient's response to an antibiotic drug regimen.

(Photo Credit: NIAID)

In the second study, which solely focused on human patients with TB, investigators observed that early changes in PET/CT scans at two months into the course of treatment could more accurately predict patient outcomes at 30 months than traditional sputum cultures. Sputum analyses can be unreliable and are limited in their ability to accurately predict treatment response and disease relapse. Based on the findings, PET/CT technology could be used in clinical trials of investigational drugs or diagnostics to predict the efficacy of a treatment regimen early on, potentially shortening the duration of a trial and saving resources, according to the researchers.

Source: NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases