A 3-dimensional model of human respiratory tissue has been shown to be an effective platform for measuring the impact of chemicals, like those found in cigarette smoke, or other aerosols on the lung.

Effective lab-based tests are required to eliminate the need for animal testing in assessing the toxicological effects of inhaled chemicals and safety of medicines. Traditional lab-based tests use cell lines that do not reflect normal lung structure and physiology, and in some cases have reduced, or loss of, key metabolic processes.

Consequently, the long-term toxicological response of the cells can differ from what actually happens in humans. Since the damaging effect of inhaled toxicants usually results from repeated exposures to low doses over a prolonged period, it is important that cell culture systems maintain their physiology, in particular the ability to metabolise chemicals over time.

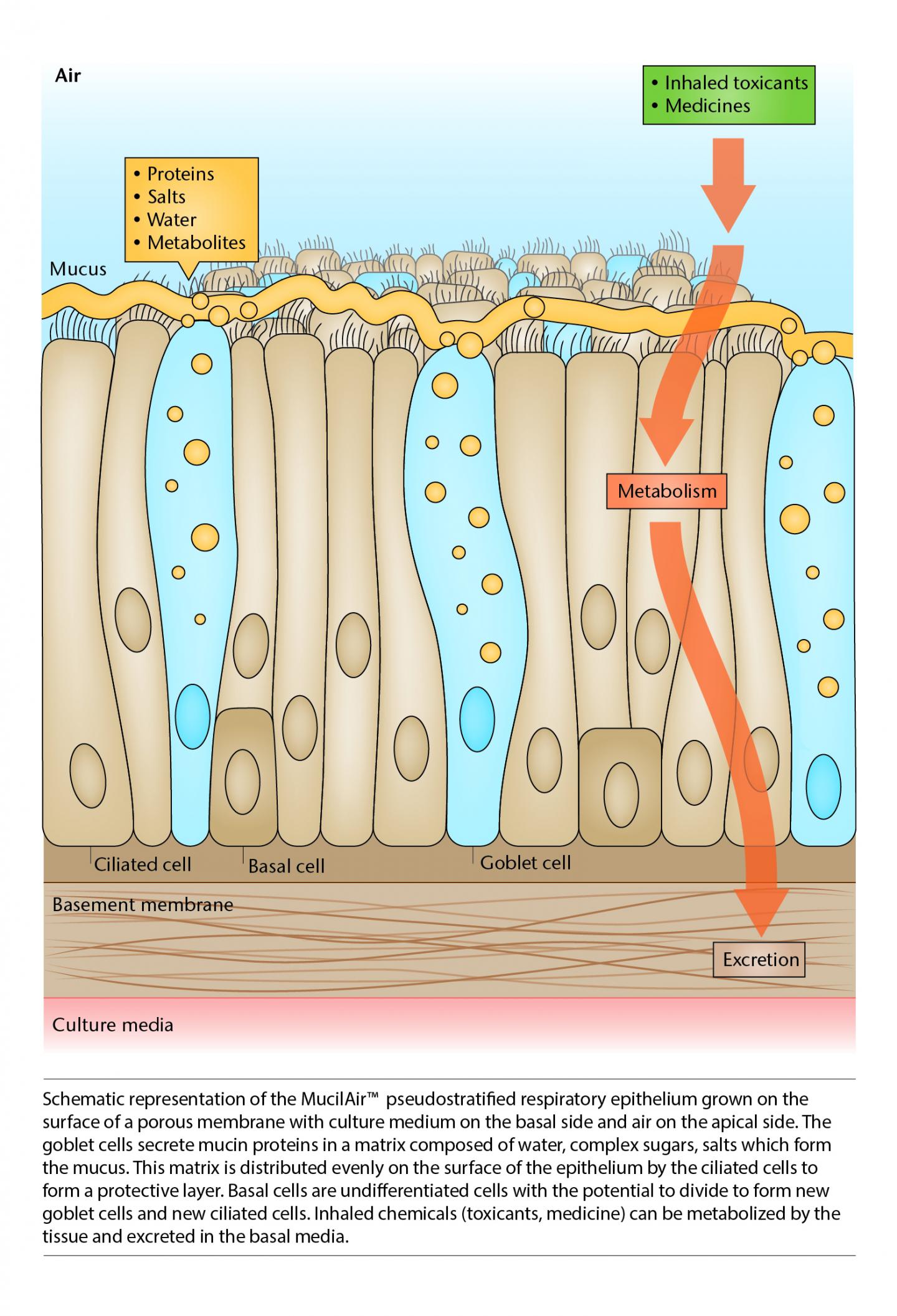

Schematic representation of the MucilAir pseudostratied respiratory epithelium grown on the surface of a porous membrane with culture medium on the basal side and air on the apical side. Credit: BAT

Scientists at British American Tobacco assessed a commercially available 3-dimensional in vitro tissue model, MucilAir™ by growing human respiratory epithelial cells at the air-liquid interface on a porous membrane - in this case nasal cells were used. The results show that the cells in the test model remain viable for at least six months, which makes this tissue model suitable for testing the impact of repeated exposures over a prolonged period, as in the case of the typical smoker. This results of this study will be published in Toxicology in Vitro.

The researchers maintained MucilAir™ in culture for six months, during which they periodically measured biomarkers that are key characteristics of normal respiratory epithelium. These included mucus secretion, cilia beat frequency, metabolic enzyme activity and gene expression.

The researchers compared the results with those from standard human sputum and metabolic gene expression in normal human lung. They found that MucilAir™ cells retain normal metabolic gene expression and key protein markers typical of the respiratory epithelium. When the MucilAir™ cultures were assessed over a period of six months, no significant changes in the expression profile of the tested proteins, metabolic genes, and metabolic activity was detected- confirming the suitability of MucilAir™ for use in long-term toxicological testing.

"The combined weight of evidence from proteomics, gene expression and protein activity demonstrates that the MucilAir™ system is far better than continuous cell lines for assessing the effect of repeated exposure to inhaled chemicals and toxicants," says senior scientist Emmanuel Minet. "Cell lines have been extensively used in research, but suffer from a key problem; they are often derived from diseased tissues and don't have normal characteristics, hence the need to use more physiologically relevant systems," he said. "Our results give clear supporting evidence that MucilAir™ has the potential to be used to test not only the effect of acute doses of toxicants and medicines but also the effect of repeated doses over time."

The researchers plan to use the model to compare the toxicological effect of repeated exposures to aerosols generated from conventional and next-generation tobacco and nicotine products. This research will be published in Toxicology in Vitro.