When you're blasting though space at more than 98 percent of the speed of light, you may need driver's insurance. Astronomers have discovered for the first time a rear-end collision between two high-speed knots of ejected matter. This discovery was made while piecing together a time-lapse movie of a plasma jet blasted from a supermassive black hole inside a galaxy located 260 million light-years from earth.

The finding offers new insights into the behavior of "light saber-like" jets that are so energized that they appear to zoom out of black hole at speeds several times the speed of light. This "superluminal" motion is an optical illusion due to their being pointed very close to our line of sight and very fast speeds.

Such extragalactic jets are not well understood. They appear to transport energetic plasma in a confined beam from the active nucleus of the host galaxy. The new analysis suggests that shocks produced by collisions within the jet further accelerate particles and brighten the regions of colliding material.

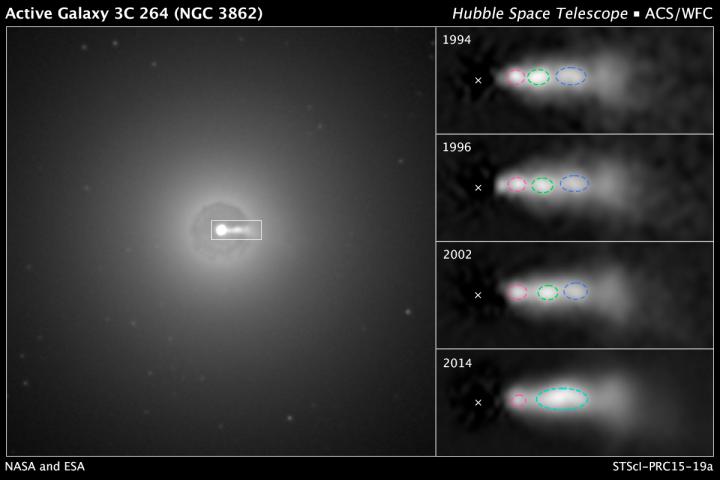

[Left] In this NASA Hubble Space Telescope image of the central region of the galaxy NGC 3862, an extragalactic jet of material moving at nearly the speed of light can be seen at the three o'clock position. The jet of ejected plasma is powered by energy from a supermassive black hole at the center of the elliptical galaxy, which is located 260 million light-years away in the constellation of Leo. [Right] A sequence of Hubble images of knots (outlined in red, green, and blue) shows them moving along the jet over a 20-year span of observing. Astronomers were surprised to discover that the central knot (green) caught up with and merged with the knot in front of it (blue). The new analysis suggests that shocks produced by collisions within the jet further accelerate particles that are confined to a narrowly focused beam of radiation. Credit: NASA, ESA, and E. Meyer (STScI)

The video of the jet was assembled with two decades' worth of NASA Hubble Space Telescope images of the elliptical galaxy NGC 3862, the sixth brightest galaxy and one of only a few active galaxies with jets seen in visible light. The jet was discovered in optical light by Hubble in 1992. NGC 3862 is in a rich cluster of galaxies known as Abell 1367, located in the constellation Leo.

The jet from NGC 3862 has a string-of-pearls structure of glowing knots of material. Taking advantage of Hubble's sharp resolution and long-term optical stability, Eileen Meyer of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland assembled a video from archival data to better understand jet motions. Meyer was surprised to see a fast knot with an apparent speed of seven times the speed of light catch up with the end of a slower moving, but still superluminal, knot along the string.

The resulting "shock collision" caused the merging blobs to brighten significantly.

"Something like this has never been seen before in an extragalactic jet," said Meyer. As the knots continue merging they will brighten further in the coming decades. "This will allow us a very rare opportunity to see how the energy of the collision is dissipated into radiation."

It's not uncommon to see knots of material in jets ejected from gravitationally compact objects, but it is rare that motions have been observed with optical telescopes, and so far out from the black hole, thousands of light-years away. In addition to black holes, newly forming stars eject narrowly collimated streamers of gas that have a knotty structure. One theory is that material falling onto the central object is superheated and ejected along the object's spin axis. Powerful magnetic fields constrain the material into a narrow jet. If the flow of the infalling material is not smooth, blobs are ejected like a string of cannon balls rather than a steady hose-like flow.

Whatever the mechanism, the fast-moving knot will burrow its way out into intergalactic space. A knot launched later, behind the first one, may have less drag from the shoveled-out interstellar medium and catch up to the earlier knot, rear-ending it in a shock collision.

Beyond the collision, which will play out over the next few decades, this discovery marks only the second case of superluminal motion measured at hundreds to thousands of light-years from the black hole where the jet was launched. This indicates that the jets are still very, very close to the speed of light even on distances that start to rival the scale of the host galaxy. These measurements can give insights into how much energy jets carry out into their host galaxy and beyond, which is important for understanding how galaxies evolve as the universe ages.

Meyer is currently making a Hubble-image video of two more jets in the nearby universe, to look for similar fast motions. She notes that these kinds of studies are only possible because of the long operating lifetime of Hubble, which has now been looking at some of these jets for over 20 years.

Extragalactic jets have been detected at X-ray and radio wavelengths in many active galaxies powered by central black holes, but only a few have been seen in optical light. Astronomers do not yet understand why some jets are seen in visible light and others are not.

Meyer's results are being reported in the May 28 issue of the journal Nature.