"A portion of the laser power is absorbed, usually via molecular transitions, and this absorption results in localized heating of the gas," Gurton explains. Molecular transitions occur when the electrons in a molecule are excited from one energy level to a higher energy level. "Since gas dissipates thermal energy fairly quickly, the modulated laser results in a rapid heat/cooling cycle that produces a faint acoustic wave," which is picked up by the microphone. Each laser in the system will produce a single tone, so, for example, six laser sources have six possible tones. "Different agents will affect the relative 'loudness' of each tone," he says, "so for one gas, some tones will be louder than others, and it is these differences that allow for species identification."

The signals produced by each laser were separated using multiple "lock-in" amplifiers -- which can extract signals from noisy environments -- each tuned for a specific laser frequency. Then, by comparing the results to a database of absorption information for a range of chemical species, the system identified each of the five gases.

Because it is optically based, the method allows for instant identification of agents, as long as the signal-to-noise ratio, which depends on both laser power and the concentration of the compound being measured, is sufficiently high, and the material in question is in the database.

Before a device based on the technique could be used in the field, Gurton says, a quantum cascade (QC) laser array with at least six "well-chosen" mid-infrared (MidIR) laser wavelengths would need to be available.

Dr. Kristan Gurton, an experimental physicist in the Battlefield Environmental Division, Computational and Information Sciences Directorate, US Army Research Laboratory, conducts experiments.

(Photo Credit: U.S. Army Research Laboratory.)

"There are groups of researchers producing QC laser arrays that will operate with sufficient power, and will house as many as 10 -- or more -- lasers at different frequencies in the spectroscopically rich region of the MidIR," he says.

Once such laser arrays are available, the method ultimately "could be tailored for a variety of detection scenarios ranging from the obvious need to protect our soldiers during conflict to civilian applications like detecting the presence of harmful chemical gases that are difficult to detect with conventional techniques," Gurton says. A sufficiently rugged device for in-the-field use, he envisions, could be about the size of a milk carton. "A photoacoustic cell is surprisingly simple and inexpensive to produce, with all of the cost and size driven primarily by the packaging of the quantum cascade laser array," he adds.

In theory, the method could be used to identify an unlimited number of chemical agents.

"In our paper we demonstrated the ability to measure as many identifying absorption features as you want," Gurton says. "You're only limited by the number of laser sources available." However, he notes, "at some point, as the number of species spectra increase in the database, a degree of spectral overlap would occur, which might result in erroneous identification. It just depends on how similar the spectra are to each other. You could have just two that have very similar spectra and that could cause problems, or you could have 20 to 30 species spectra that all have distinguishable features that can be identified easily."

This laser is used to optically "heat" very small particles.

(Photo Credit: U.S. Army Research Laboratory)

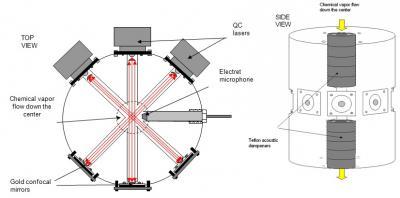

A device based on selective real-time detection of gaseous nerve agent stimulants using multi-wavelength photoacoustics could look like this, in which now "multiple" lasers are used.

(Photo Credit: U.S. Army Research Laboratory)

Source: Optical Society of America