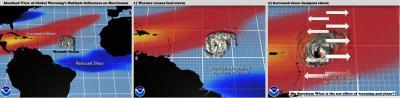

Climate model simulations for the 21st century indicate a robust increase in wind shear in the tropical Atlantic due to global warming, which may inhibit hurricane development and intensification. Historically, increased wind shear has been associated with reduced hurricane activity and intensity. This new finding is reported in a study by scientists at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science at the University of Miami and NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL) in Princeton, N.J. Warmer oceans feed storms, yet increased wind shear is able to also impair their intensity. Credit: NOAA GFDL

Warmer oceans feed storms, yet increased wind shear is able to also impair their intensity. Credit: NOAA GFDL

While other studies have linked global warming to an increase in hurricane intensity, this study is the first to identify changes in wind shear that could counteract these effects. "The environmental changes found here do not suggest a strong increase in tropical Atlantic hurricane activity during the 21st century," said Brian Soden, Rosenstiel School associate professor of meteorology and physical oceanography and the paper’s co-author. However, the study does identify other regions, such as the western tropical Pacific, where global warming does cause the environment to become more favorable for hurricanes.

"Wind shear is one of the dominant controls to hurricane activity, and the models project substantial increases in the Atlantic," said Gabriel Vecchi, lead author of the paper and a research oceanographer at GFDL. "Based on historical relationships, the impact on hurricane activity of the projected shear change could be as large – and in the opposite sense – as that of the warming oceans."

Examining possible impacts of human-caused greenhouse warming on hurricane activity, the researchers used climate models to assess changes in the environmental factors tied to hurricane formation and intensity. They focused on projected changes in vertical wind shear over the tropical Atlantic and its ties to the Pacific Walker circulation – a vast loop of winds that influences climate across much of the globe and that varies in concert with El Niño and La Niña oscillations. By examining 18 different models, the authors identified a systematic increase in wind shear over much of the tropical Atlantic due to a slowing of the Pacific Walker circulation. Their research suggests that the increase in wind shear could inhibit both hurricane development and intensification.

"This study does not, in any way, undermine the widespread consensus in the scientific community about the reality of global warming," said Soden. "In fact, the wind shear changes are driven by global warming."

The authors also note that additional research will be required to fully understand how the increased wind shear affects hurricane activity more specifically. "This doesn't settle the issue; this is one piece of the puzzle that will contribute to an incredibly active field of research," Vecchi said.

Source: University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science.