CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Most people have trouble telling them apart, but bumble bees, honey bees, stingless bees and solitary bees have home lives that are as different from one another as a monarch's palace is from a hippie commune or a hermit's cabin in the woods. A new study of these bees offers a first look at the genetic underpinnings of their differences in lifestyle.

The study focuses on the evolution of "eusociality," a system of collective living in which most members of a female-centric colony forego their reproductive rights and instead devote themselves to specialized tasks – such as hunting for food, defending the nest or caring for the young – that enhance the survival of the group. The study appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Eusociality is a rarity in the animal world, said Gene Robinson, a University of Illinois entomology professor and the director of the Institute for Genomic Biology, who led the study. Ants, termites, some bees and wasps, a few other arthropods and a couple of mole rat species are the only animals known to be eusocial.

Among bees, there are the "highly eusocial" honey bees and stingless bees, with a caste of sterile workers and a queen that functions primarily as a "giant, egg-laying machine," Robinson said. And there are other, so-called "primitively eusocial" insects, usually involving a single mom who starts a nest from scratch and then, once she has raised enough workers, "kicks back and becomes a queen," he said.

Illinois entomology professor Sydney Cameron, a collaborator on the study and a social insect evolution expert, dislikes the term "primitively eusocial" because it suggests that these bees are on their way to becoming more like stingless bees or honey bees. Eusociality is not a progressive evolution from the "primitive" to the "advanced" stage, she said.

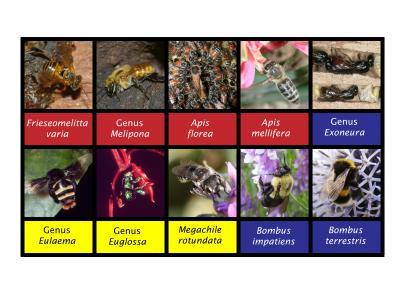

A new study found significant differences in gene sequence between 10 species of eusocial (red and blue) and non-eusocial (yellow) bees. The researchers also saw patterns of genetic change unique to either the highly (red) or primitively (blue) eusocial bees. The bees used in the study were: Frieseomelitta varia, Melipona quadrifasciata (pictured: Melipona eburnea), Apis florea, Apis mellifera, Exoneura robusta (pictured: Exoneura angophorae), Eulaema nigrita (pictured: Eulaema meriana), Euglossa cordata (pictured: Euglossa sp.), Megachile rotundata, Bombus impatiens, Bombus terrestris.

(Photo Credit: Photos provided by (clockwise from top left): Claus Rasmussen; Claus Rasmussen; Zachary Huang; Zachary Huang; Michael Schwarz; Edward Ross; Benjamin Bembé; Theresa Pitts-Singer, USDA; James Whitfield; James Whitfield.)

"They're not striving to become highly eusocial," Cameron said. "They don't say to themselves, 'If only I could become a honey bee!' "

"People talk about the evolution of eusociality," Robinson said. "But we want to emphasize that these were independent evolutionary events. And we wanted to trace the independent stories of each."

To accomplish this, the researchers worked with Roche Diagnostic Corp. to sequence active genes (those transcribed for translation into proteins) in nine species of bees representing every lifestyle from the solitary leaf-cutter bee, Megachile rotundata, to the highly eusocial dwarf honey bee, Apis florea. Then Illinois crop sciences professor and co-author Matt Hudson used the only available bee genome, that of the honey bee, Apis mellifera, as a guide to help assemble and identify the sequenced genes in the other species, and the team looked for patterns of genetic change that coincided with the evolution of the differing social systems.

"Are there genes that are unique to the primitively eusocial bees that aren't found in the highly eusocial bees?" Cameron said. "Or if you lump all the eusocial bees together, are there unique genes that unite those groups compared to the solitaries?"

The analysis did find significant differences in gene sequence between the eusocial and solitary bees. The researchers also saw patterns of genetic change unique to either the highly eusocial or primitively eusocial bees. The frequency and pattern of these changes in gene sequence suggest "signatures of accelerated evolution" specific to each type of eusociality, and to eusociality in general, the researchers reported.

"What we find is that there are some genes that show signatures of selection across the different independent evolutions (of eusocial bees)," Robinson said. "They might be representatives of the 'gotta have it' genes if you're going to evolve eusociality. But others are more lineage-specific."