In 2009, published genome-wide DNA data was not available for a single ancient human individual. Today, there is genome-wide data available for more than 6,000 ancient humans. This rapid expansion of ancient DNA (aDNA) research enables scientists to uncover more information than ever on past human populations, including their genetic adaptations, patterns of migration and mixing, and even clues about our species’ deep past. But this wide availability of aDNA brings ethical questions on how the data is gathered and used to the forefront. Now a team of more than 60 scholars from 31 countries has articulated a set of ethical guidelines regarding aDNA as a way to govern such research globally.

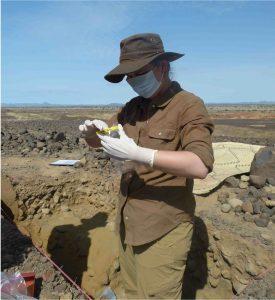

The authors, which include Elizabeth Sawchuk, PhD, a Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Anthropology at Stony Brook University, and a Research Associate of the Turkana Basin Institute, contend that the ethics of aDNA research has a particular urgency because of the rapid growth of the field, the societal and political impacts of studying ancestry, and the fact that aDNA work analyzes once living people who must be respected.

Any research that pursues questions about the past by generating genetic data from archaeologically derived human tissues, such as skeletal remains, constitutes aDNA research. Such work has revealed new information about individuals and events anywhere from hundreds to thousands of years old.

Sawchuk believes that establishing a globally applicable set of guidelines is a turning point in the field of aDNA research.

“Since the first fully sequenced ancient human genome was published in 2010, we have been operating in what some have characterized as a rather chaotic ancient DNA revolution,” says Sawchuk. “After years of public outcry to establish clear universal guidelines for ethical research in this field, our paper attempts to do just that. The work represents the largest effort to date to create global guidelines for aDNA research developed by a team of diverse archeologists, curators, geneticists and other stakeholders. I think our guidelines will fundamentally shift the way the field operates and will have a long-lasting impact.”

The authors point out that much of the literature thus far on the ethics of aDNA research has centered around North America. Their research presents global case studies that illustrate the breadth of issues surrounding the identification of community and Indigenous groups, and stress that researchers need to recognize that there are global differences in the meaning of Indigeneity.

The team together assessed a range of issues related to carrying out research on ancient human remains, with a specific focus on different research contexts and diverse perspectives held by those conducting research as well as other stakeholders – which may include Indigenous peoples, descendants and/or guardian communities, museum curators, and others with a connection to the ancient individuals sampled.

Using this approach, the international team of scholars developed what they believe is a strong and universally applicable set of ethical guidelines summarized by five points:

- Researchers must ensure that all regulations are followed in the places where they work, including all local regulations.

- Prepare a detailed plan prior to beginning any study.

- Minimize damage to human remains.

- Ensure that data are made available following publication to allow critical reexamination of the scientific findings.

- Engage with other stakeholders from the beginning of a study to ensure respect and sensitivity to stakeholder perspectives.

Key to ensuring ethical practices and sensitivity when conducting aDNA research, say the authors, is to identify and consult with the stakeholders and communities appropriate to specific research contexts and questions. This should occur from the very beginning of a study, alongside the creation of a detailed plan for how research will be conducted, and results shared.

Another key guideline involves making aDNA data available to other scientists for the purpose of replication once research is complete, so scientific results can be independently confirmed without the need for additional destructive sampling. Researchers should also engage with how their findings are communicated and understood, and correct misrepresentations when appropriate.

As an anthropologist who studies ancient human remains, Sawchuk particularly supports the guideline aimed at minimizing damage to remains.

“As our only direct link to people who experienced life in the past, human remains must be respected and carefully conserved. We must balance the potential benefits of aDNA research with the impacts on skeletal collections, and always remember that we are studying other human beings,” she stressed.