"The nation that controls magnetism will control the universe," famed fictional detective Dick Tracy predicted back in 1935. Probably an overstatement, but there's little doubt the nation that leads the development of advanced magnetoelectronic or "spintronic" devices is going to have a serious leg-up on its Information Age competition. A smaller, faster and cheaper way to store and transfer information is the spintronic grand prize and a key to winning this prize is understanding and controlling a multiferroic property known as "spontaneous magnetization."

Now, researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have been able to enhance spontaneous magnetization in special versions of the popular multiferroic material bismuth ferrite. What's more, they can turn this magnetization "on/off" through the application of an external electric field, a critical ability for the advancement of spintronic technology.

"Taking a novel approach, we've created a new magnetic state in bismuth ferrite along with the ability to electrically control this magnetism at room temperature," says Ramamoorthy Ramesh, a materials scientist with Berkeley Lab's Materials Sciences Division, who led this research. "An enhanced magnetization arises in the rhombohedral phases of our bismuth ferrite self-assembled nanostructures. This magnetization is strain-confined between the tetragonal phases of the material and can be erased by the application of an electric field. The magnetization is restored when the polarity of the electric field is reversed."

Ramesh, who also holds appointments with the University of California Berkeley's Department of Materials Science and Engineering and the Department of Physics, is the corresponding author of a paper in the journal Nature Communications titled "Electrically Controllable Spontaneous Magnetism in Nanoscale Mixed Phase Multiferroics."

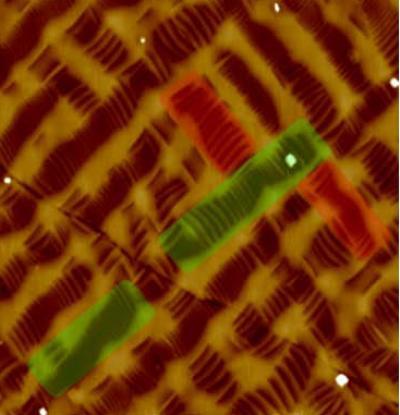

In this atomic force microscopy topography image of a special mixed phase bismuth ferrite sample, red and green shaded areas indicate two sets of mixed phase regions oriented at 90 degrees to each other.

(Photo Credit: Image from Ramesh group)

Magnetoelectronic or spintronic devices store data through electron spin and its associated magnetic moment rather than the electron charge-based storage of today's electronic devices. Spin, a quantum mechanical property arising from the magnetic moment of a spinning electron, carries a directional value of either "up" or "down" that can be used to encode data in the 0s and 1s of the binary system. In addition to the size, speed and capacity advantages over electronic devices, the data storage in spintronic devices does disappear when the electric current stops.

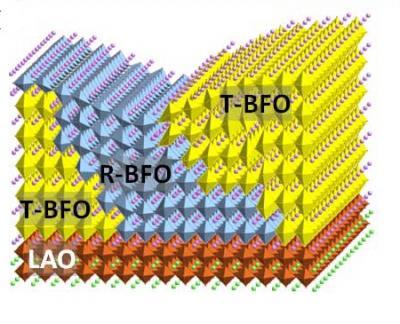

Multiferroics are prime candidate materials for future spintronic devices because they can simultaneously exhibit both electric and magnetic properties. Bismuth ferrite, a multiferroic comprised of bismuth, iron and oxygen (BFO), has been thrust into the spintronic spotlight thanks in part to a surprising discovery in 2009 by Ramesh and his research group. They found that although bismuth ferrite is an insulator, running through its crystals are two-dimensional sheets called "domain walls" that conduct electricity. Ramesh and his group subsequently found that application of a large epitaxial strain (compression in the direction of a material's crystal planes) changes the bismuth ferrite crystal structure from its natural rhombohedral phase into a tetragonal phase. Partial relaxation of the strain creates a stable nanoscale mixture of the rhombohedral and tetragonal phases.

In this new research, Ramesh and his group have deployed epitaxial strain to create bismuth ferrite films that are a mix of highly distorted rhombohedral and tetragonal phases, in which the rhombohedral phases are mechanically confined by regions of the tetragonal phases. The magnetic moments that spontaneously arise in these special films occur within the distorted rhombohedral phase rather than at the phase interfaces and are significantly stronger than the magnetic moment that occurs in conventional bismuth ferrite.

The schematic shows the structural arrangement of rhombohedral and tetragonal phases in a special bismuth ferrite film -- magnetization is confined to the rhombohedral phase.

(Photo Credit: Image from Ramesh group)

"Normal bismuth ferrite films typically show a spontaneous magnetization of 6 to 8 electromagnetic units/cubic centimeter, which is too small for applications in a real device," says Qing (Helen) He, who was the lead author on the Nature Communications paper. "By setting our bismuth ferrite films in this special mixed phase state, we can enhance the spontaneous magnetization to approximately 30 to 40 electromagnetic units/cubic centimeter, which is large enough to be used in real devices."

Ramesh, He and their co-authors discovered that the enhanced spontaneous magnetization in their special bismuth ferrite films can be controlled through the use of an external electric field without any noticeable current passing through the film. The ability to turn the magnetization on/off in these films opens the door to their use in spintronic devices as the on/off states can serve as the 1 and 0 states of data storage. That these on/off states can be achieved without an electric current is a significant added advantage.

"In the typical magnetic memory device, the magnetic state of the material is set by an external magnetic field that is generated from the current flowing through an electromagnet," says He. "Current flow needs to be driven with a lot of power and at the same time generates waste heat. Therefore, using an electric field instead of a current to control the magnetization saves energy."

The discovery that the magnetization of these special bismuth ferrite films can be controlled with an electric field was largely made possible by the use of PhotoEmission Electron Microscopy (PEEM) at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source (ALS), a DOE Office of Science national user facility for synchrotron radiation. The PEEM3 microscope at ALS beamline 11.0.1 is one of the world's best instruments for studying ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic nanoscale domains.

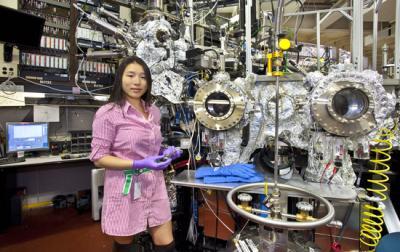

Helen He, lead author of a paper describing a unique new bismuth ferrite film featuring enhanced and controllable magnetization, made extensive use of the PEEM3 microscope at Berkeley Lab's Advanced Light Source.

(Photo Credit: Photo by Roy Kaltschmidt, Berkeley Lab Public Affairs.)