The majority of disease-causing bacteria in the body are rendered harmless by the protective effects of the immune system. Those that manage to escape the immune system can be killed by antibiotics, but bacteria are becoming more and more resistant to more and more antibiotics. Meet Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, a bacterial predator that is an efficient killer of Gram-negative bacteria, such as the prevalent E. coli bacterium. It is present in soil and, just like E. coli, it can also be found in the human gut, where a complex ecosystem of bacterial inhabitants exists.

This ferocious bacterial predator enters its prey and devours it from the inside while dividing into four or six progenies. It then bursts open its prey and starts its hunt for the next. B. bacteriovorus is a formidable opponent: It is not only an efficient killer, but it is also extremely fast. Although the bacterium itself is hardly one micrometer long, it can reach speeds of 160 micrometers per second, making it the "world champion" in speed swimming and ten times faster than the E. coli.

"Knowledge of defense and attack mechanisms in bacteria is crucial for future development of potential alternatives to antibiotics," explains Dr. Daniel Koster, from the department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

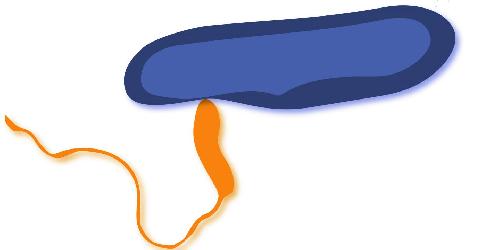

Predator bacteria Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus (in yellow) enters its prey E. coli (in blue). Credit: Felix Hol

Predator bacteria Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus (in yellow) enters its prey E. coli (in blue). Credit: Felix Hol

"B. bacteriovorus kills bacteria by a whole different mechanism of action than classical antibiotics, and as such, predatory bacteria might in the future constitute a viable alternative to these antibiotics," Koster says.

Koster led the research together with scientists from The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience at TU Delft in The Netherlands.

In order to understand how E. coli is able to survive in the presence of such an effective predator, the researchers created two different environments for the bacteria.

The first one mimicked the micro-scale features of soil, consisting of 85 chambers, each 100x100x15 micrometers in size, linked by a narrow channel. The second environment was an open space of a similar size, without the thin channel. These environments were made in a controlled fashion using micro-fabrication techniques.

The team of researchers, comprised of experts from various fields -- from microbiology to nanotechnology, from ecology to biophysics -- published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: In the open environment, which can be compared to a bare open surface, E. coli did not stand a chance to survive. Most of the population was eliminated within a couple of hours. But it proved surprisingly able to maintain a healthy population in an environment with many small chambers. Koster explained how E. coli was able to survive in the fragmented environment: "It seems that groups of E. coli 'hide' in the many corners of the fragmented environment, where they readily stick as bio-films that probably protect them against B. bacteriovorus. Our findings provide important information because in natural environments, such as our gut, the bacterium also lives in fragmented spaces."

It is not yet known precisely how E. coli is able to defend itself against predatory bacteria, but the research contributes to the understanding of the behavior of the predatory bacteria, which could become a possible alternative to antibiotics in the future.

"In the future, predatory bacteria might for example be genetically modified to specifically target harmful bacteria, while leaving benign bacteria untouched. As such, B. bacteriovorus might be more selective than the antibiotics currently in use, and anti-bacterial treatment might not require the widespread extermination of the gut flora that is of importance to human health."

source: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem