The history of Britain’s population is a familiar story to many. It tells of an ancient people (retrospectively dubbed the Celts) and subsequent invasion and settlement by the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans and Vikings. And many people today still identify strongly with one or another of these groups.

However, historical records have their weaknesses. For example, it’s very difficult to know to what extent an invasion amounted to mass settlement replacing an existing population, and how much it was a small elite converting that existing population to a new way of life.

For some years, geneticists have been able to answer similar questions on a continental scale. Now, enough data has been collected to start to tackle some of these issues on a national level. The People of the British Isles (PoBI) project examined differences at more than 500,000 positions in the DNA of more than 2,000 people from the UK, thus creating the most detailed genetic map of any country in the world.

In a paper published in Nature, the authors describe how they looked for regional differences in genetic patterns and inferred ancestry from various past migrations.

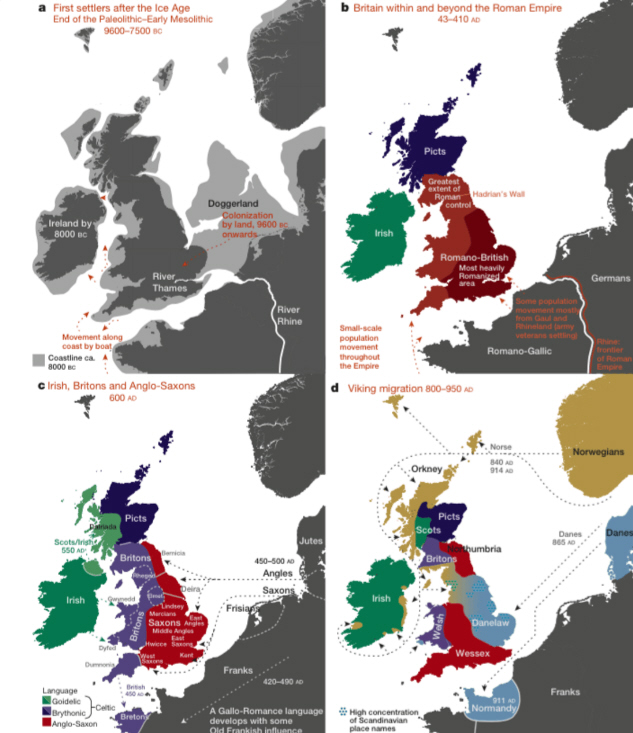

European movements, as understood by historians. Many of these distinctions are now supported by genetic data. Credit: Nature.

Splitting the population

First, they split the samples into the two most-different groups possible, without considering where each sample came from. This process was repeated, splitting off the next most distinct group and then the next, producing an increasingly subtle picture of diversity.

By then plotting these groups onto the map, it became clear that many of them were clustered in particular regions, suggesting a clear geographical pattern to genetic diversity in Britain. So, for example, the first split separated Orkney from the rest of the British Isles. This means that Orkney is more genetically distinct from the rest of the UK than any other regions are from each other.

It’s important to remember that these groups have much ancestry in common, and are in no way pure representations of historical peoples. In fact, those historical peoples themselves cannot be truly defined. However, similarities between modern populations in the UK and continental Europe can suggest where past migrations came from. To this end, DNA was collected from ten other European countries, and these too were divided based on their genetic diversity. These European groups were then compared to the British ones.

It wasn’t all Vikings

‘Viking’ times. mararie, CC BY

‘Viking’ times. mararie, CC BY

When compared to the various continental groups, 25% of DNA from Orkney appears to have come from the groups found in Norway.

This supports the long-held belief that Norse Vikings settled Orkney, but also shows that the majority of Orcadian ancestry predates this settlement.

However, Orkney was not the only area of the country to have been conquered by Vikings. The Danelaw was a large area of northern and eastern England, ruled over by Danish Vikings. Interestingly, the study found no genetic signature of this, suggesting that the Danelaw was overwhelmingly inhabited by pre-existing English people, and ruled over by a very small number of Danes.

Neolithic Skara Brae on Orkney. The DNA of these pre-Viking people still accounts for much of today’s Orcadian DNA. John Lord, CC BY

Scottish, English and Welsh

After Orkney, the second split separated Wales from the rest of the UK; the third, north from south Wales; the fourth, the far-north of England, Scotland, and Northern Ireland collectively from the rest of England; and the fifth, Cornwall from most of England. This shows that the “Celtic” groups are all genetically distinct from “Anglo-Saxon” England, but also from each other, and, for example, the Scottish and English are more similar to each other than either is to the Welsh.

Scottish and English more similar to each other than to the Welsh. khrawlings, CC BY

However the “Celtic” groups all had large contributions of ancestry from the same three continental groups (centred on France, Belgium and Germany), suggesting some common, but very ancient ancestry from Pre-Saxon peoples. Indeed, these three groups also contribute significant ancestry across the UK, suggesting that these pre-Saxon people were widespread, and nowhere were they completely replaced.

Another very notable feature is that, even after the population was split into 50 groups, almost half the samples remain in one large group, covering most of central, southern and eastern England. As this region has little in the way of geographical or political barriers, it appears that freedom of movement over the centuries has homogenised the genetics of its people. The people of this region have much ancestry from pre-Saxon groups, but also 10-40% from continental groups who barely contributed to the Welsh gene-pool at all. It seems altogether very likely that these were the Anglo-Saxons.

Outside the history books

The study also found evidence of migrations not found in history books. These include contributions from France, Spain and Scandinavia, after the peopling of Britain, but probably before the Saxon invasions, and even a later one from France into Wales which didn’t seem to go through England.

So by drawing such conclusions from high-resolution data, the PoBI project uncovers the movements of ordinary people, rather than the ruling classes emphasised by traditional approaches. They also provide a proof-of-principle for similar work around the world, and some applications for modern healthcare geneticists. Michael Dunn, Head of Genetics and Molecular Sciences at the Wellcome Trust, said:

These researchers have been able to use modern genetic techniques to provide answers to the centuries old question – where we come from. Beyond the fascinating insights into our history, this information could prove very useful from a health perspective, as building a picture of population genetics at this scale may in future help us to design better genetic studies to investigate disease.

![]()

Daniel Zadik, Postdoctoral researcher in genetics at University of Leicester. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.