A new study provides the first conclusive proof of the existence of a space wind first proposed theoretically over 20 years ago. By analysing data from the European Space Agency's Cluster spacecraft, researcher Iannis Dandouras detected this plasmaspheric wind, so-called because it contributes to the loss of material from the plasmasphere, a donut-shaped region extending above the Earth's atmosphere. The results are published today in Annales Geophysicae, a journal of the European Geosciences Union (EGU).

"After long scrutiny of the data, there it was, a slow but steady wind, releasing about 1 kg of plasma every second into the outer magnetosphere: this corresponds to almost 90 tonnes every day. It was definitely one of the nicest surprises I've ever had!" said Dandouras of the Research Institute in Astrophysics and Planetology in Toulouse, France.

The plasmasphere is a region filled with charged particles that takes up the inner part of the Earth's magnetosphere, which is dominated by the planet's magnetic field.

To detect the wind, Dandouras analysed the properties of these charged particles, using information collected in the plasmasphere by ESA's Cluster spacecraft. Further, he developed a filtering technique to eliminate noise sources and to look for plasma motion along the radial direction, either directed at the Earth or outer space.

As detailed in the new Annales Geophysicae study, the data showed a steady and persistent wind carrying about a kilo of the plasmasphere's material outwards each second at a speed of over 5,000 km/h. This plasma motion was present at all times, even when the Earth's magnetic field was not being disturbed by energetic particles coming from the Sun.

Researchers predicted a space wind with these properties over 20 years ago: it is the result of an imbalance between the various forces that govern plasma motion. But direct detection eluded observation until now.

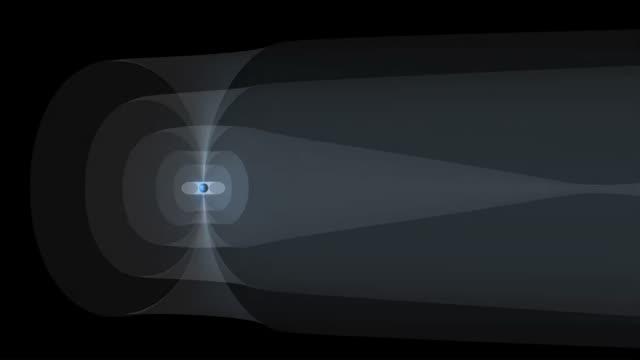

This animation shows the Earth's plasmasphere -- the innermost part of our planet's magnetosphere -- and the plasmaspheric wind, an outward flow of charged particles. The doughnut-shaped plasmasphere is centred around the Earth's equator and rotates along with it. The steady plasmaspheric wind continuously transfers material from the plasmasphere into the magnetosphere, releasing about 1 kg of plasma every second -- almost 90 tonnes a day -- into the outer magnetosphere.

(Photo Credit: ESA/ATG medialab)

"The plasmaspheric wind is a weak phenomenon, requiring for its detection sensitive instrumentation and detailed measurements of the particles in the plasmasphere and the way they move," explains Dandouras, who is also the vice-president of the EGU Planetary and Solar System Sciences Division.

The wind contributes to the loss of material from the Earth's top atmospheric layer and, at the same time, is a source of plasma for the outer magnetosphere above it. Dandouras explains: "The plasmaspheric wind is an important element in the mass budget of the plasmasphere, and has implications on how long it takes to refill this region after it is eroded following a disturbance of the planet's magnetic field. Due to the plasmaspheric wind, supplying plasma – from the upper atmosphere below it – to refill the plasmasphere is like pouring matter into a leaky container."

The plasmasphere, the most important plasma reservoir inside the magnetosphere, plays a crucial role in governing the dynamics of the Earth's radiation belts. These present a radiation hazard to satellites and to astronauts travelling through them. The plasmasphere's material is also responsible for introducing a delay in the propagation of GPS signals passing through it.

"Understanding the various source and loss mechanisms of plasmaspheric material, and their dependence on the geomagnetic activity conditions, is thus essential for understanding the dynamics of the magnetosphere, and also for understanding the underlying physical mechanisms of some space weather phenomena," says Dandouras.

Michael Pinnock, Editor-in-Chief of Annales Geophysicae recognises the importance of the new result. "It is a very nice proof of the existence of the plasmaspheric wind. It's a significant step forward in validating the theory. Models of the plasmasphere, whether for research purposes or space weather applications (e.g. GPS signal propagation) should now take this phenomenon into account," he wrote in an email.

Similar winds could exist around other planets, providing a way for them to lose atmospheric material into space. Atmospheric escape plays a role in shaping a planet's atmosphere and, hence, its habitability.

Source: European Geosciences Union