End-stage liver disease or liver cirrhosis is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States, and approximately half of these cases are related to alcohol consumption. There's no refuting that alcohol itself harms the liver, but new research in mice and humans published February 10 in Cell Host & Microbe reveals that chronic drinking also promotes the growth of gut bacteria that can travel to the liver and exacerbate liver disease.

Gastroenterologist Bernd Schnabl of the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine and his colleagues found that chronic alcohol consumption suppresses the mouse antibacterial defense system in the intestine. It does so by blocking intestinal cells' ability to produce natural antibiotic proteins (called REG3B and REG3G).

"Intestinal bacteria can now not only proliferate, but also slowly migrate through the intestinal wall," says Schnabl. "Since the liver encounters all the blood coming from the intestine, not only important nutrients but also bacteria can now reach the liver. The direct damage that is caused by alcohol to the liver is augmented by the arrival of these gut bacteria, through mechanisms that are currently unknown."

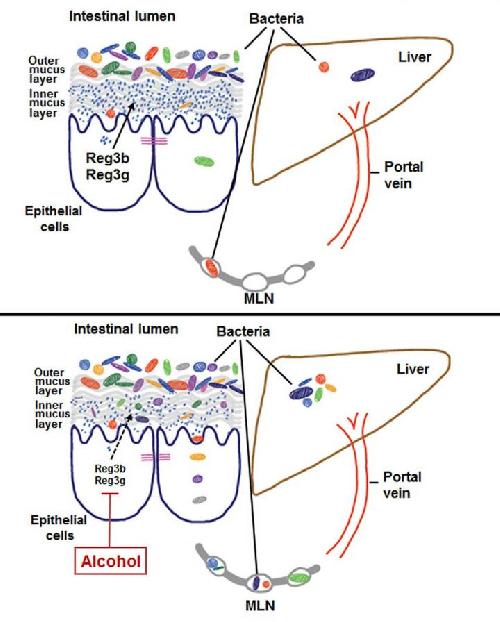

The mechanism by which chronic alcohol consumption alters the microbial composition in the intestine is unknown. This visual abstract depicts how alcohol reduces intestinal expression of REG3 lectins, increasing the number of mucosa-associated bacteria. The subsequent translocation of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes and liver exacerbates alcoholic liver disease. Credit: Wang et al./Cell Host & Microbe 2016

The mechanism by which chronic alcohol consumption alters the microbial composition in the intestine is unknown. This visual abstract depicts how alcohol reduces intestinal expression of REG3 lectins, increasing the number of mucosa-associated bacteria. The subsequent translocation of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes and liver exacerbates alcoholic liver disease. Credit: Wang et al./Cell Host & Microbe 2016

The team also found that mice genetically engineered to lack REG3G had more of these bacteria after consuming alcohol, and they developed more severe alcoholic liver disease than their littermates. However, restoring REG3G to the intestine reduced the levels of bacteria that traveled to the liver and protected against alcohol-induced liver damage.

Finally, the researchers found that humans with alcohol dependency had elevated levels of bacteria in their small intestines. The team's previous research showed that they also had lower levels of REG3G.

While it may be best for patients at risk of liver disease to stop drinking altogether, Schnabl notes that it can be difficult for some to do so. These latest findings indicate that it may be possible to help patients with alcoholic liver disease by boosting their intestinal defense against certain bacteria, for example by encouraging the growth of good (probiotic) bacteria or by stimulating the production of intestinal antibiotics such as REG3G.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism states that "low-risk" drinking levels for men are no more than 4 drinks on any single day and no more than 14 drinks per week. For women, "low-risk" drinking levels are no more than three drinks on any single day and no more than 7 drinks per week. (http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Hangovers/beyondHangovers.htm)

source: Cell Press