Fast radio bursts are quick, bright flashes of radio waves from an unknown source in space. They are a mysterious phenomenon that last only a few milliseconds, and until now they have not been observed in real time. An international team of astronomers, including three from the Carnegie Observatories, has for the first time observed a fast radio burst happening live. Their work is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

There is a great deal of scientific interest in fast radio bursts, particularly in uncovering their origin. Only seven fast radio bursts have previously been discovered, since the first one found in 2007. All were found retroactively by combing through data from the Parkes radio telescope in eastern Australia and the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico.

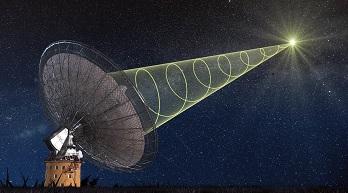

illustration of CSIRO's Parkes radio telescope receiving the polarized signal from the new fast radio burst. Credit: Swinburne Astronomy Productions

"These events are one of the biggest mysteries in the Universe" noted Carnegie Observatories' Acting Director John Mulchaey. "Until now, astronomers were not able to catch one of these events in the act."

"These bursts were generally discovered weeks or months or even more than a decade after they happened! We're the first to catch one in real time," said Emily Petroff, a PhD candidate from Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne, Australia and lead author of the publication. Swinburne is a member institution of the ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO).

In order to observe the fast radio burst in real time, the team mobilized 12 telescopes around the world and in space, including Carnegie's Magellan and Swope telescopes. Each telescope followed-up on the original burst observation at different wavelengths.

Measurements of the interaction between previously detected fast radio burst's flashes and the free electrons their signals encountered in space as they traveled to reach us had previously indicated that the bursts likely originated far outside of our galaxy. But the idea was controversial.

The team's data indicates that the burst originated up to 5.5 billion light years away. This means that the sources of theses bursts are extremely bright and could perhaps be used as a cosmological tool for measuring and understanding our universe once we come to understand them better.

"Together, our observations allowed the team to rule out some of the previously proposed sources for the bursts, including nearby supernovae," explained Carnegie's Mansi Kasliwal who was on the team along with Mulchaey and colleague Yue Shen. "Short gamma-ray bursts are still a possibility, as are distant magnetic neutron stars called magnetars, but not long gamma ray bursts."

Gamma ray bursts are high-energy explosions that form some of the brightest celestial events. Long bursts can signify energy released during a supernova and are followed by an afterglow, which emits lower wavelength radiation than the original explosion.

Another interesting piece of information the team was able to gather about the burst is its polarization. The orientation of the radio waves indicates that the burst likely originated near or passed through a magnetic field, information that can help narrow down potential sources going forward.

"As we continue to search for the source of fast radio bursts, Carnegie is well positioned to make big strides in the field," Mulchaey said. "Quick access to big telescopes like Magellan may be the key to solving this mystery."

Other co-authors are: M. Bailes (Swinburne University of Technology and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); E.D. Barr (Swinburne University of Technology and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); B. R. Barsdell (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics); N. D. R. Bhat (ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics and Curtin University) ; F. Bian (Australian National University); S. Burke-Spolaor (Caltech); M. Caleb(Australian National University, Swinburne University of Technology, ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); D. Champion (Max Planck Institut für Radioastronomie); P. Chandra (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research Pune University Campus); G. Da Costa (Australian National University); C. Delvaux (Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik); C. Flynn (Swinburne University of Technology and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); N. Gehrels (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center); J. Greiner (Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik); A. Jameson (Swinburne University of Technology and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); S. Johnston (CSIRO Astronomy & Space Science Australia Telescope National Facility); E. F. Keane (Swinburne University of Technology and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); S. Keller (Australian National University); J. Kocz (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech); M. Kramer (Max Planck Institut für Radioastronomie and University of Manchester) G. Leloudas (University of Copenhagen and Weizmann Institute of Science); D. Malesani (University of Copenhagen); C. Ng (Max Planck Institut für Radioastronomie); E. O. Ofek (Weizmann Institute of Science); D. A. Perley (Caltech); A. Possenti (Osservatorio Astronomico di Cagliari); B. P. Schmidt (Australian National University and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); B. Stappers (University of Manchester); P. Tisserand (Australian National University and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics); W. van Straten (Swinburne University of Technology and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics ); and C. Wolf (Australian National University and ARC Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics).