Naturally, our brain activity waxes and wanes. When listening, this oscillation synchronizes to the sounds we are hearing. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences have found that this influences the way we listen. Hearing abilities also oscillate and depend on the exact timing of one's brain rhythms. This discovery that sound, brain, and behaviour are so intimately coupled will help us to learn more about listening abilities in hearing loss.

Our world is full of cyclic phenomena: For example, many people experience their attention span changing over the course of a day. Maybe you yourself are more alert in the morning, others more in the afternoon. Bodily functions cyclically change or "oscillate" with environmental rhythms, like light and dark, and this in turn seems to govern our perception and behaviours. One might conclude that we are slaves to our own circadian rhythms, which in turn are slaves to environmental light–dark cycles.

A hard-to-prove idea in neuroscience is that such couplings between rhythms in the environment, rhythms in the brain, and our behaviours are also present at much finer time scales. Molly Henry and Jonas Obleser from the Max Planck Research Group "Auditory Cognition" now followed up on this recurrent idea by investigating the listening brain.

This idea holds fascinating implications for the way humans process speech and music: Imagine the melodic contour of a human voice or your favourite piece of music going up and down. If your brain becomes coupled to, or "entrained" by, these melodic changes, Henry and Obleser rea-soned, then you might also be better prepared to expect fleeting but important sounds occurring in what the voice is saying, for example, a "d" versus a "t".

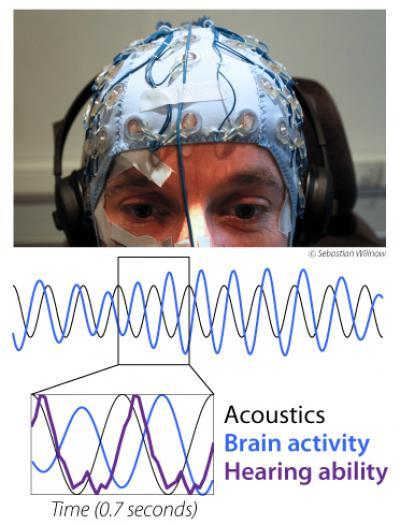

Listeners' brain rhythms synchronize with the acoustic stimulus, which causes hearing abilities to "oscillate".

(Photo Credit: Sebastian Willnow)

The simple "fleeting sound" in the scientists' experiment was a very short and very hard-to-detect silent gap (about one one-hundredth of a second) embedded in a simplified version of a melodic contour, which slowly and cyclically changed its pitch at a rate of three cycles per second (3 Hz).

To be able to track each listener's brain activity on a millisecond basis, Henry and Obleser record-ed the electroencephalographic signal from listeners' scalps. First, the authors demonstrated that every listener's brain was "dragged along" (this is what entrainment, a French word, literally means) by the slow cyclic changes in melody; listeners' neural activity waxed and waned. Second, the listeners' ability to discover the fleeting gaps hidden in the melodic changes was by no means constant over time. Instead, it also "oscillated" and was governed by the brain's waxing and wan-ing. The researchers could predict from a listener's slow brain wave whether or not an upcoming gap would be detected or would slip under the radar.

Why is that? "The slow waxings and wanings of brain activity are called neural oscillations. They regulate our ability to process incoming information", Molly Henry explains. Jonas Obleser adds that "from these findings, an important conclusion emerges: All acoustic fluctuations we encoun-ter appear to shape our brain's activity. Apparently, our brain uses these rhythmic fluctuations to be prepared best for processing important upcoming information".

The researchers hope to be able to use the brain's coupling to its acoustic environment as a new measure to study the problems of listeners with hearing loss or people who stutter.

Source: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft