Bioengineers at the University of California, San Diego have proven that when it comes to guiding stem cells into a specific cell type, the stiffness of the extracellular matrix used to culture them really does matter. When placed in a dish of a very stiff material, or hydrogel, most stem cells become bone-like cells. By comparison, soft materials tend to steer stem cells into soft tissues such as neurons and fat cells. The research team, led by bioengineering professor Adam Engler, also found that a protein binding the stem cell to the hydrogel is not a factor in the differentiation of the stem cell as previously suggested. The protein layer is merely an adhesive, the team reported Aug. 10 in the advance online edition of the journal Nature Materials.

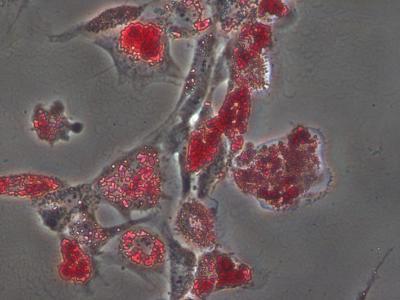

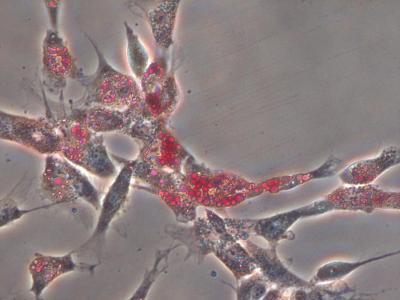

Cells grown on hydrogels of the same stiffness all display fat cell markers and deform the underlying matrix material the same way.

(Photo Credit: Adam Engler, UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering)

Their findings affirm Engler's prior work on the relationship between matrix stiffness and stem cell differentiations.

"What's remarkable is that you can see that the cells have made the first decisions to become bone cells, with just this one cue. That's why this is important for tissue engineering," said Engler, a professor at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering.

Engler's team, which includes bioengineering graduate student researchers Ludovic Vincent and Jessica Wen, found that the stem cell differentiation is a response to the mechanical deformation of the hydrogel from the force exerted by the cell. In a series of experiments, the team found that this happens whether the protein tethering the cell to the matrix is tight, loose or nonexistent. To illustrate the concept, Vincent described the pores in the matrix as holes in a sponge covered with ropes of protein fibers. Imagine that a rope is draped over a number of these holes, tethered loosely with only a few anchors or tightly with many anchors. Across multiple samples using a stiff matrix, while varying the degree of tethering, the researchers found no difference in the rate at which stem cells showed signs of turning into bone-like cells. The team also found that the size of the pores in the matrix also had no effect on the differentiation of the stem cells as long as the stiffness of the hydrogel remained the same.

Cells grown on three hydrogels of the same stiffness all display fat cell markers and deform the underlying matrix material in the same way.

(Photo Credit: Adam Engler, UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering)

"We made the stiffness the same and changed how the protein is presented to the cells (by varying the size of the pores and tethering) and ask whether or not the cells change their behavior," Vincent said. "Do they respond only to the stiffness? Neither the tethering nor the pore size changed the cells."

"We're only giving them one cue out of dozens that are important in stem cell differentiation," said Engler. "That doesn't mean the other cues are irrelevant; they may still push the cells into a specific cell type. We have just ruled out porosity and tethering, and further emphasized stiffness in this process."

Cells grown on three hydrogels of the same stiffness all display fat cell markers and deform the underlying matrix material in the same way.

(Photo Credit: Adam Engler/UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering)