To find out more, the researchers let male and female big brown bats fly alone and in pairs while tempting them with tethered mealworms. Careful analysis of video and audio recordings of the bats' flight paths and calls, respectively, revealed sequences of three to four calls, both longer in duration and lower in frequency than the big brown bats' echolocation pulses. For reasons that the researchers can't entirely explain yet, only males make those calls.

The males who emitted those calls were more likely to attack the mealworm while the other male moved farther away. Almost always—96% of the time, to be exact—the researchers could trace calls back to the specific male that made them, based on the calls' unique features.

Wright says she doesn't really know why only males make the foraging calls. Females do have to eat, but they may more often forage near related individuals in comparison to males. Some male bats also make mating calls that are similar in some respects to the newly described foraging calls, suggesting that they may have carried them over from use in one context to another. Whatever the answer, the findings are a reminder of the impressive social lives of bats as they go about their fast-paced, night lives.

"Male big brown bats use individually distinct social calls to repel other bats and increase their own chances of getting a meal," Wright says.

"Acoustic communication in bats may be more sophisticated than was previously understood."

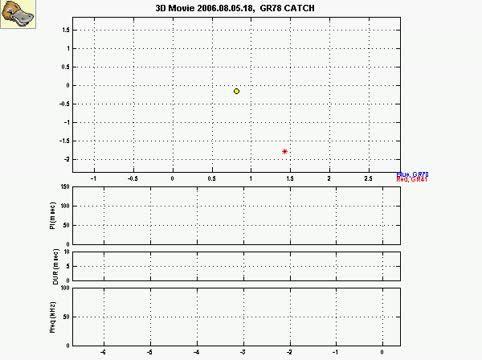

This is an animation of a recording from a trial with two male bats competing for prey. Red and blue each represent a bat (red = GR41 and blue = GR78), and the synchronized audio and video data have been slowed 10x. Each circle represents a vocalization emitted by that bat, with green circles representing social calls. The bottom portion of the screen shows attributes of each call emitted by the bats, including the start and end frequency and duration of each pulse, as well as the interval from the start of one pulse to the start of the next. The portion of the video in which the bats disappear then reappear from another location is due to the bats temporarily leaving the field of view of both cameras. In this trial, GR78 emits social calls around 00:11 and 00:34. Prior to the social call emitted around 00:11, GR41 is approaching a tethered mealworm and initiates a buzz but appears to abort the attack following social call emission by GR78, who captures the prey near the end of the trial.

(Photo Credit: Current Biology, Wright et al.)

As big brown bats wake up from their winter slumber and start zooming around in pursuit of insects to eat, how do they coordinate their activities in the dark of night? For one thing, according to researchers who report their findings on March 27 in the Cell Press journal Current Biology, males do it by telling other males to back off. In so doing, those vocal males -- each with their own distinctive calls -- increase their chances of a meal.

(Photo Credit: Genevieve Spanjer Wright)

Source: Cell Press