In an interstellar race against time, astronomers have measured the space-time warp in the gravity of a binary star and determined the mass of a neutron star--just before it vanished from view.

The international team, including University of British Columbia astronomer Ingrid Stairs, measured the masses of both stars in binary pulsar system J1906. The pulsar spins and emits a lighthouse-like beam of radio waves every 144 milliseconds. It orbits its companion star in a little under four hours.

"By precisely tracking the motion of the pulsar, we were able to measure the gravitational interaction between the two highly compact stars with extreme precision," says Stairs, professor of physics and astronomy at UBC.

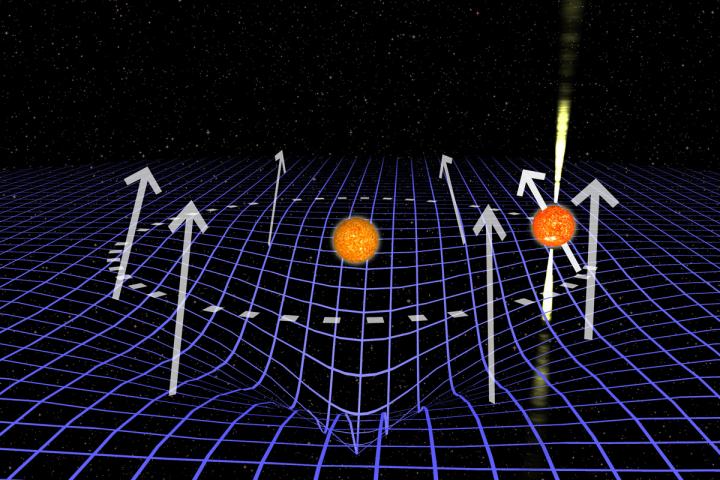

One orbit of pulsar J1906 (on the right, with radio beams) around its companion (centered), with space-time curvature (blue grid). Joeri van Leeuwen.

"These two stars each weigh more than the Sun, but are still over 100 times closer together than the Earth is to the Sun. The resulting extreme gravity causes many remarkable effects."

According to general relativity, neutron stars wobble like a spinning top as they move through the gravitational well of a massive, nearby companion star. Orbit after orbit, the pulsar travels through a space-time that is curved, which impacts the star's spin axis.

Animation of the effect of geodetic precession in the observer pulsar. Two neutron stars orbit one another. The star visible as a pulsar shows rotating beams. The companion is frozen at the frame center. In a flat space-time, where the companion is massless but the pulsar does orbit it for illustrative purpose, the pulsar rotation axis (represented by the arrow) is unchanged after one orbit. Once the companion mass increases to the measured 1.32 solar mass (about half a million Earth masses, but in a sphere only 10 kilometer across), space-time curves. Within one orbit, the pulsar axis now slants (the effect is exaggerated 1 million times here). Because of that change, the pulsar is now all but invisible from Earth. Credit: Joeri van Leeuwen/ASTRON, License CC-BY-AS

"Through the effects of the immense mutual gravitational pull, the spin axis of the pulsar has now wobbled so much that the beams no longer hit Earth," explains Joeri van Leeuwen, an astrophysicist at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, and University of Amsterdam, who led the study.

"The pulsar is now all but invisible to even the largest telescopes on Earth. This is the first time such a young pulsar has disappeared through precession. Fortunately this cosmic spinning top is expected to wobble back into view, but it might take as long as 160 years."

The mass of only a handful of double neutron stars have ever been measured, with J1906 being the youngest. It is located about 25,000 light years from Earth. The results were published in the Astrophysical Journal and presented at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Seattle on January 8.