"We've been fortunate enough to see all stages of this process, with a range of ground and space telescopes. We've been looking for such evidence for more than a decade," said Dr Alessandro Papitto, the Nature paper's lead author. Dr Papitto is an astronomer of the Institute of Space Studies (ICE, CSIC-IEEC) of Barcelona.

The pulsar and its companion form what is called a 'low-mass X-ray binary' system. In such a system, the matter transferred from the companion lights up the pulsar in X-rays and makes it spin faster and faster, until it becomes a 'millisecond pulsar' that spins at hundreds of times a second and emits radio waves. The process takes about a billion years, astronomers think.

In its current state the pulsar is exhibiting behaviour typical of both kinds of systems: millisecond X-ray pulses when the companion is flooding the pulsar with matter, and radio pulses when it is not.

"It's like a teenager who switches between acting like a child and acting like an adult," said Mr John Sarkissian, who observed the system with CSIRO's Parkes radio telescope.

"Interestingly, the pulsar swings back and forth between its two states in just a matter of weeks."

The pulsar was initially detected as an X-ray source with the European Space Agency's INTEGRAL satellite. X-ray pulsations were seen with another satellite, ESA's XMM-Newton; further observations were made with NASA's Swift. NASA's Chandra X-ray telescope got a precise position for the object.

Then, crucially, the object was checked against the pulsar catalogue generated by CSIRO's Australia Telescope National Facility, and other pulsar observations. This established that it had already been identified as a radio pulsar.

The source was detected in the radio with CSIRO's Australia Telescope Compact Array, and then re-observed with CSIRO's Parkes radio telescope, NRAO's Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope in the USA, and the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope in The Netherlands. Pulses were detected in a number of these later observations, showing that the pulsar had 'revived' as a normal radio pulsar only a couple of weeks after the last detection of the X-rays.

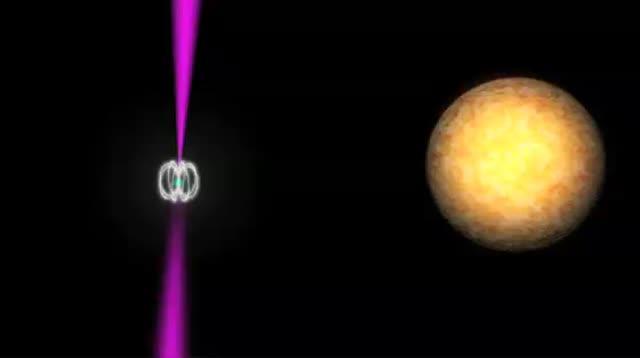

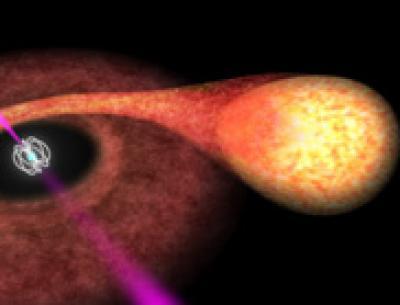

The aging pulsar rotates slower and slower, then matter from its companion spins it up again. As the pulsar is spun up, it alternates between emitting X-rays (white) and radio waves (pink).

(Photo Credit: ESA)

This is an artist's impression of the pulsar and its companion star.

(Photo Credit: ESA)

Source: CSIRO Australia