ATHENS, Ohio (May 21, 2013)—The mighty T. rex may have thrashed its massive head from side to side to dismember prey, but a new study shows that its smaller cousin Allosaurus was a more dexterous hunter and tugged at prey more like a modern-day falcon.

"Apparently one size doesn't fit all when it comes to dinosaur feeding styles," said Ohio University paleontologist Eric Snively, lead author of the new study published today in Palaeontologia Electronica. "Many people think of Allosaurus as a smaller and earlier version of T. rex, but our engineering analyses show that they were very different predators."

Snively led a diverse team of Ohio University researchers, including experts in mechanical engineering, computer visualization and dinosaur anatomy. They started with a high-resolution cast of the five-foot-long skull plus neck of the 150-million-year-old predatory theropod dinosaur Allosaurus, one of the best known dinosaurs. They CT-scanned the bones at O'Bleness Memorial Hospital in Athens, which produced digital data that the authors could manipulate in a computer.

Snively and mechanical engineer John Cotton applied a specialized engineering analysis borrowed from robotics called multibody dynamics. This allowed the scientists to run sophisticated simulations of the head and neck movements Allosaurus made when attacking prey, stripping flesh from a carcass or even just looking around.

"The engineering approach combines all the biological data—things like where the muscle forces attach and where the joints stop motion—into a single model. We can then simulate the physics and predict what Allosaurus was actually capable of doing," said Cotton, an assistant professor in the Russ College of Engineering and Technology.

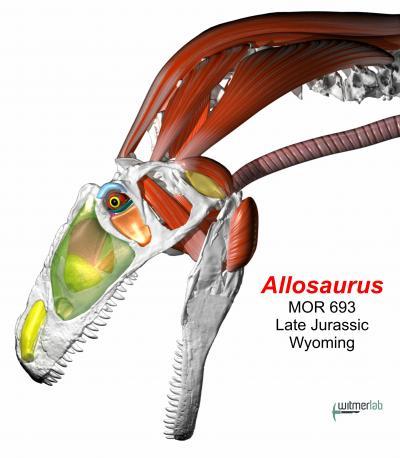

This illustration shows skeleton and soft tissues of the head and neck of the late Jurassic predatory dinosaur Allosaurus.

(Photo Credit: WitmerLab, Ohio University)

To figure out how Allosaurus de-fleshed a Stegosaurus, the team had to "re-flesh" Allosaurus. The anatomical structure of modern-day dinosaur relatives, such as birds and crocodilians, combined with tell-tale clues on the dinosaur bones, allowed Snively and anatomists Lawrence Witmer and Ryan Ridgely to build in neck and jaw muscles, air sinuses, the windpipe and other soft tissues into their Allosaurus 3D computer model.

"Dinosaur bones simply aren't enough," said Witmer, Chang Professor of Paleontology in the Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine and principal investigator on the National Science Foundation's Visible Interactive Dinosaur Project that provided funding for this research. "We need to know about the other tissues that bring the skeleton to life."

A key finding was an unusually placed neck muscle called longissimus capitis superficialis. In most predatory dinosaurs, such as T. rex, which Snively studied previously, this muscle passed from the side of the neck to a bony wing on the outer back corners of the skull.

"This neck muscle acts like a rider pulling on the reins of a horse's bridle," explained Snively. "If the muscle on one side contracts, it would turn the head in that direction, but if the muscles on both sides pull, it pulls the head straight back."

But the analysis of Allosaurus revealed that the longissimus muscle attached much lower on the skull, which, according to the engineering analyses, would have caused "head ventroflexion followed by retraction."

"Allosaurus was uniquely equipped to drive its head down into prey, hold it there, and then pull the head straight up and back with the neck and body, tearing flesh from the carcass … kind of like how a power shovel or backhoe rips into the ground," Snively said.

In the animal world, this same de-fleshing technique is used by small falcons, such as kestrels. Tyrannosaurs like T. rex, on the other hand, were engineered to use a grab-and-shake technique to tear off hunks of flesh, more like a crocodile.

But the team's engineering analyses revealed a cost to T. rex's feeding style: high rotational inertia. That large bony and toothy skull perched at the end of the neck made it hard for T. rex to speed up or slow down its head or to change its course as it swung its head around.

Allosaurus, however, had a relatively very light head, which the team discovered as they restored the soft tissues and air sinuses.

Having a lot of mass sitting far away from the axis of head turning, as in T. rex, increases rotational inertia, whereas having a lighter head, as in Allosaurus, decreases rotational inertia, the researchers explained. An ice skater spins faster and faster as she tucks her arms and legs into her body, decreasing her rotational inertia as the mass of her limbs moves closer to the axis of spinning.

"Allosaurus, with its lighter head and neck, was like a skater who starts spinning with her arms tucked in," said Snively, "whereas T. rex, with its massive head and neck and heavy teeth out front, was more like the skater with her arms fully extended … and holding bowling balls in her hands. She and the T. rex need a lot more muscle force to get going."

The end result is that Allosaurus was a much more flexible hunter that could move its head and neck around relatively rapidly and with considerable control. That control, however, came at the cost of brute-force power, requiring a de-fleshing style that, like a falcon, recruited the whole neck and body to strip flesh from the bones.

The Ohio University team will continue to use their engineering approach to explore additional differences in dinosaur feeding styles.

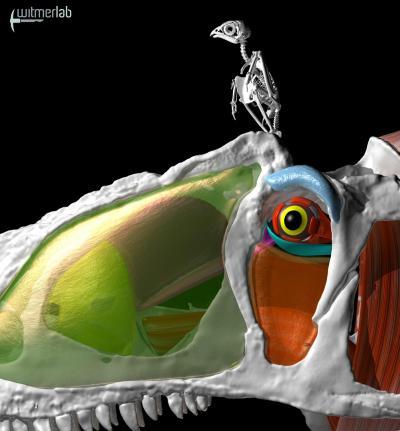

A modern-day kestrel (a small falcon) is perched atop the skull of the Jurassic predatory dinosaur Allosaurus. A key finding of the new study is that Allosaurus had a feeding style similar to falcons. In both cases, tearing flesh from carcasses involved grasping meat with the jaws and tugging back and up with the neck and body.

(Photo Credit: WitmerLab, Ohio University)

This animation shows head and neck movements of the Jurassic predatory dinosaur Allosaurus.

(Photo Credit: WitmerLab, Ohio University)

Source: Ohio University