Since the days of Darwin, biologists have questioned why certain plants occur in widely separated places, the farthest reaches of North American and the Southern tip of South America but nowhere in between. How did they get there? An international team of researchers have now found an important piece of the puzzle: migratory birds about to fly to South America from the Arctic harbor small plant parts in their feathers.

In the past several decades, scientists have discovered that the North – South distributions of certain plants often result from a single jump across the tropics, not as a result of gradual movements or events that occurred over a hundred million years ago. These single jumps across the tropics have led many to speculate that migratory birds play a role, however those claims have remained speculative.

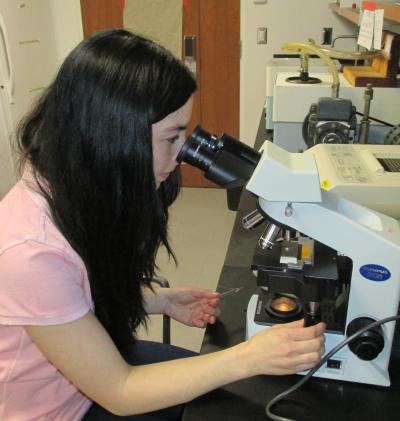

A team of 10 biologists, including three undergraduate students, collected feathers in the field and used microscopes to closely examine them. They found a total of 23 plant fragments that were trapped in the feathers of long-distance migratory birds about to leave for South America.

The fragments were all thought to be able to grow into new plants hence indicating that they could be used to establish new plant populations. Several of the plant parts belonged to mosses, which are exceptionally tough plants. About half of all moss species can self-fertilize to produce offspring, and many can grow as clones. For these plants, it only takes a single successful dispersal event to establish a new population.

Among the researchers working on the project are three students for whom this was the first experience with scientific research.

"We really had no idea what we might find," said Emily Behling, a senior studying biology at the University of Connecticut. "Each feather was like a lottery ticket, and as we got further into the project I was ecstatic about how many times we won."

In addition to mosses, researchers looking at the bird feathers found spores, plant pieces and other things that could help explain the distribution of cyanobacteria, fungi, and algae.

Lily Lewis a PhD candidate at the University of Connecticut explained, "Mosses are especially abundant and diverse in the far Northern and Southern reaches of the Americas, and relative to other types of plants, they commonly occur in both of these regions, yet they have been largely overlooked by scientists studying this extreme distribution. Mosses can help to illuminate the processes that shape global biodiversity."

Each year 500,000 American golden-plovers (pictured) fly between Arctic N. America and South America with potentially hundreds of thousands of diaspores trapped in their feathers.

(Photo Credit: Jean-François Lamarre, CC BY SA)

The study, titled "First evidence of bryophyte diaspores in the plumage of transequatorial migrant birds", was published today in PeerJ, a peer-reviewed open access journal in which all articles are freely available to everyone (https://PeerJ.com).

Emily Behling looks for microscopic plant parts using a protocol she and two other students developed.

(Photo Credit: Lily Lewis, CC BY SA)

Source: PeerJ