According to the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, 22% of Australian men and 29% of women aged 20 to 29 have at least one tattoo.

In a 2013 survey conducted by Sydney-based McCrindle Research, a third of people with tattoos regretted them to some extent, and 14% had looked into or started the removal process. Laser removal has become cheaper and more readily available, but there are serious safety concerns around cheap lasers, poorly-trained operators and the risk of serious burns and scars to clients.

Currently, guidelines on who can operate lasers and IPL machines vary widely by state. The Sydney Morning Herald reported yesterday that national guidelines drawn up by the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency are due to go out for public consultation later this month.

But there’s a bigger picture here. If 14% of people have looked into tattoo removal, and a third of those inked regret the decision to some extent, a clear majority seem happy with their choice. And in this, they form part of a rich and meaningful history.

The history of the tattoo

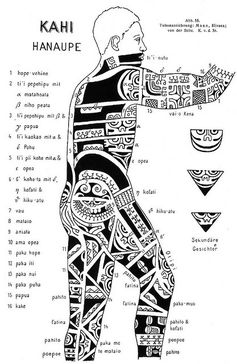

The word “tattoo” comes from the Samoan word “tatau” and was communicated back to Europe by explorers, to denote acts of scarring, pricking, painting and staining of the body that was pursued by various Polynesian cultures.

An illustration that interprets traditional Polynesian tattoos.John Curran/Flickr

Tattooing existed in various traditional societies – such as Japan and India – but it was Polynesia that really intrigued European explorers and sailors. The impact of Polynesian tattooing upon Western consciousness is evident in Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851). The heavily-tattooed character Queequeg, is from an elite family (he is the son of a chieftan) who enthrals his comrades with stories of cannibalism.

His tattoos are described by the narrator as “twisted,” and a “patchwork quilt”, and take on great significance throughout the novel.

So in the first instance, for modern Westerners, tattooing represented the exotic and the primitive. We should remember that Western societies were then not secular, and Christianity directly forbade tattoos:

Do not cut your bodies for the dead or put tattoo marks on yourselves. I am the LORD. (Leviticus 19:27-29)

The body was considered the site of sin. Going to the trouble of inserting ink on the skin – no matter how beautiful the patterns – must have seemed like something only a pagan (such as Melville’s Queequeg) would contemplate.

The 20th-century tattoo

The story of how tattoos became part of mainstream culture is largely a 20th-century phenomenon. Tattoos were first adopted by non-mainstream sections of the population such as sailors, the military and prison populations.

Sailors adopted the custom of tattooing from the cultures they visited.Charles Fenno Jacobs/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

These were populations that had low degrees of individuality and a high degree of conformity. They also tended to be segments of the population with low social status – although the level of prestige attached to the cultural symbols of low status groups has changed over time.

Before tattooing became mainstream, two things had to happen.

First, it had to become more acceptable for large segments of the population to become interested in body-adornment. Second, tattooing had to lose its marginal status and acquire a dose of glamour.

The body as the site of aesthetic presentation had to loose its stigma. It had to become permissible to use the skin as a surface for adornment and inscription.

You have to remember that, until quite recently, the only acceptable form of body modification was ear-piercing – and that was only available to women of a certain age. So our attitudes to using the body as a canvas, or material that could be sculpted, had to change before tattooing could be embraced en masse.

The growth in tattooing required that things which were considered bohemian or countercultural became mainstream or part of mass culture. Once upon a time, blue jeans, drug consumption, or motorcycle riding were considered outsider pursuits.

Everyday aesthetics can signify conformity in subcultures, such as this 80s punk youth culture.Paul Townsend

Because young people are key consumers of popular culture, and because they like to differentiate themselves from older generations, it is no surprise that young people were the major adopters of tattoos and other symbols of outsider status, once they became glamorous.

So what do tattoos say about our culture?

When tattooing reflected membership of a community, or an outsider group, this tended to exclude large sections of the population but it did mean that tattooing was largely permanent and reflective of a coherent way of life.

As tattooing became more of a fashion statement, and less emblematic of group membership, it has become something we are more likely to regret or change our minds about. In an age of Ikea furnishings and short-term commitments, personal style is no longer permanent.

Today, we are not born into a tattooed culture; we choose to join the ranks of the tattooed. And, increasingly, it is not even about joining subcultures or adopting a whole way of life. Rather, tattooing has become an individual act of consumption akin to other styling or decorative choices.

Of course, getting a tattoo possesses a seriousness that shopping for a new garment or changing one’s hairstyle do not.

Thus, while our consumer and youth-driven cultures are a long way from the Polynesian societies that Captain Cook came across, getting a tattoo is still an aesthetic decision with strong ritual and existential overtones.

And, there will always be tattooing aficionados who like to differentiate themselves from the mainstream by choosing patterns that are more obscure, having more of their body covered, or who indicate the aesthetic value they attach to tattooing by referring to it as “body art”.

Tattooing is a more serious aesthetic decision than many others we routinely make because, unlike tanning or cosmetics, tattoo ink is inscribed upon our bodies and removal requires significant expense, effort and specialist knowledge. There is something hard-won and more difficult to reverse about a tattooed body.

Perhaps that’s part of tattooing’s ongoing mystique. Even in a culture driven by fashion, some choices we make have a longevity and significance that other mundane choices do not![]() .

.

Eduardo de la Fuente is Senior Lecturer in Creativity and Innovation at James Cook University. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.